Note: This is the second in a five-part series on the Black Gospel Music Preservation Program made possible by generous funding from the Prichard Family Foundation.

The influence of Black gospel music on other genres makes it ripe for study, understanding and appreciation, according to those who are collecting and preserving it for future generations at Baylor University’s Black Gospel Music Preservation Program. With an archive of 5,000 vinyl records on the shelves and 48,000 digital tracks, the program is the largest repository of its type in the world.

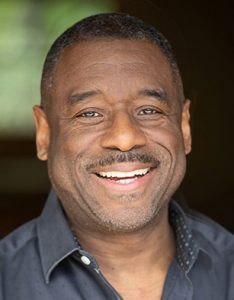

Stephen Newby, who is leading the program as the inaugural Lev H. Prichard III Chair in the Study of Black Worship, said the Baylor collection provides a place and forum to study Black “cultural codes” as described by William Banfield in his book, Cultural Codes: Makings of a Black Music Philosophy.

“We get to pay attention to the cues, clues and the codes of what happens in Black life,” Newby said. “By archiving recordings, archiving sermons, it allows us to simply pay attention, and to transcribe, and to see what is happening with this people group. And particularly from a Christian university, (to ask) who is God for this group of people? Where do they come from, where are they going, and what do they have?”

Newby, who came to Baylor in July from Seattle Pacific University and is himself a composer and former worship pastor for 25 years at a multi-ethnic church in the Seattle area, said Black gospel music should be studied alongside all other genres that are studied.

“Our language must continue to expand, especially our artistic language.”

“In order to really articulate the language of gospel music, it must be studied. The life and the legacy of this music must be studied deeply because we’re Americans,” he said. “You know, it’s no longer just Bach, Beethoven and Brahms, but we’re listening to Sibelius and Stravinsky and Miles Davis and Duke Ellington and Walter Hawkins and Andraé Crouch. Our language must continue to expand, especially our artistic language.”

A brief history of Black gospel music

“The Golden Gate Quartet” in 1964. (Wikipedia)

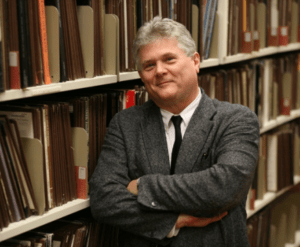

Robert Darden, archive founder and professor emeritus of journalism at Baylor, said Black gospel music grew out of the spirituals in the early 1920s and 1930s in a form called “jubilee,” which was basically arranged spirituals with groups like the Golden Gate Jubilee Quartet leading the way. And then came “gospel blues” with Blind Willie Johnson among the best-known artists and performers of that style.

“So, we get people writing original religious compositions with a beat. And then it’s people like Thomas Dorsey and three or four other people who are writing simple songs much like spirituals only with a verse and a chorus,” he said. “They’re taking the lyrics from Sunday night and setting it to the beat of Saturday night. And then it goes on and it morphs from Dorsey’s kind of gentle swinging gospel to hard gospel quartets which would be close to soul music.”

“They’re taking the lyrics from Sunday night and setting it to the beat of Saturday night.”

Everything came to a stop with the start of World War II, Darden said, but then gospel music entered what’s regarded as its “golden age” beginning in 1945 when the end of war-time travel restrictions and vinyl restrictions put gospel groups back on the road and their records back in the stores.

“Gospel artists were able to make a living and tour the country on regular routes, even if it was taking their Green Book with them. They could make a living doing the music they loved. They could go to big and small places,” he explained. “Record sales were such and attendance was such that they could do this, and they needed to do this to get better at it. And so the artists got increasingly professional, increasingly influential as the music spread wider and wider.”

Robert Darden

While the sales per capita for Black gospel music weren’t what they are now, it was part of the fabric of African American life, Darden said.

“Most churches hosted gospel artists periodically. The church was the center of the Black community. The Civil Rights movement opened things up, but the only thing that had been there before was the church,” he continued. “And for the first time, gospel artists began to appear on TV and began to break into venues like Carnegie Hall and Radio City Music Hall and buying Black gospel radio stations. Only three or four radio stations in the country were even owned by Blacks for so long.”

As the reach and audience of the music expanded, so did its influence on younger artists who tried to copy and emulate it, especially in Europe, Darden said.

“The British invasion came in the ’60s, and all those guys almost down to the person always talk about Black gospel music,” he said. “And there would have been kids growing up hearing that in the 1940s and ’50s. In the 1960s, they’re trying to put their spin on that style.”

As an example, Darden told how Black gospel singer and guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe toured the United Kingdom just once in 1957, but her unique guitar style influenced a generation of British guitarists including Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones.

“The British invasion brought Black music back here, and then American musicians were trying to recreate it and they didn’t realize it’d been here all along.”

“They all said, ‘I want to do that,’ and there’s probably not a whole lot otherwise in common between Keith Richards and Rosetta,” he said. “The British invasion brought Black music back here, and then American musicians were trying to recreate it and they didn’t realize it’d been here all along.”

Meanwhile, Black gospel music remained strong in the Black community and especially the church.

“It came out of the Black community, and it was their music. They created it. It was played primarily for Blacks. They administered and nurtured and suckled it,” he said. “And the artists would always come back to their hometown and do a big homecoming concert. You knew those people, or at least you knew the family.”

Darden said the “golden age,” as delineated by the Baylor program, ended around 1975 with the introduction of new recording media such as cassettes and changes in the music itself, but Black gospel music has continued to evolve with artists like Andraé Crouch bringing jazz, funk and Caribbean rhythms.

“And Andraé leads on to the Winans and Kirk Franklin, and now the next big phase from that is a praise and worship style of gospel. Choirs go in and out of fashion, solos go in and out, quartets too. It’s just similar to other genres,” he said. “The only thing that separates gospel from all the others is it must have evangelical lyrics of some kind — must have some kind of religious lyrics. If it does not have that, it may still be great, but then it becomes … whatever.”

American gospel singer Sister Rosetta Tharpe (1915 – 1973) performs at a Blues and Gospel Caravan tour in the UK, 1964. (Photo by Tony Evans/Getty Images)

International appeal

Both Darden and Newby note the continued international appeal of Black gospel music. Indeed, a quick Google search with the words “gospel” and “Europe,” for example, spins out listings for concerts and festivals that feature gospel music. One of the largest is the Stockholm Gospel Choir Festival, which in August brought together professional artists and an amateur choir of 1,000 singers for workshops and concerts. Similarly, Museum Catharijneconvent, the national Dutch museum for the art, culture and history of Christianity, hosted a multimedia exhibition in late 2022 titled “Gospel, A Musical Journey of Spirit and Hope.”

“Oh my, gospel music is so big in Western Europe, particularly Scandinavia,” Darden noted. “It’s massive; the Netherlands, it’s huge. Andraé Crouch has been gone 10 years, and they’re still having benefit concerts for Andraé, big bands, I mean, crazy.”

Stephen Newby

Newby tells how in the late 1990s he toured Europe with a youth orchestra with Black gospel in the repertoire.

“We considered it a concert of American music. We did Copland, we did Bernstein, we did music of Thomas Dorsey and Walter Hawkins, and they heard it as American,” he said. “And so, when you go overseas, they are very aware of the sophistication of the artistic language that’s coming out of America. And as we expand the gospel music archives in this program, we want to continue to explore how gospel music has infiltrated hip-hop and how hip-hop has infiltrated gospel music.”

And, Newby adds, this exploration must also consider how to ensure future generations don’t miss out on this musical heritage.

“We must pose the question: Is there a generation gap in the Black church with regard to the gospel and how spirituals are performed, how gospel music is performed, how Black hymnody is executed in our liturgies?” he said. “And it’s not just for the Black communities but for everybody. That’s the beautiful thing because we expect people to be well rounded. ‘Study your German and your French. Well, study your African American musical heritage.’”

The Black Gospel Music Preservation Program was founded in 2006 and is accessible in person through a state-of-the-art listening center at Baylor’s Moody Memorial Library. Digitized recordings can be heard from anywhere via the library’s online digital collections. The program partners with the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Related articles:

Black Gospel Music Preservation Program: Securing the legacy of Black Gospel music

Baylor’s Black Gospel Music Preservation Program names new leader

Baylor’s Black Gospel Archive and Listening Center now open to the public

Baylor endows new academic chair in study of Black worship