Had things gone according to his father’s wishes, He Qi would be one of China’s leading mathematicians today.

But history — and more specifically Mao Tse-tung and his Cultural Revolution — had other ideas.

“I was a teenage boy and a high school student when I was sent to the countryside to do labor work,” He says. It quickly became clear he wouldn’t survive long, given his tall-but-slender frame.

“I was thinking I was not strong enough … so what can I do?”

The answer, which he now considers inspired, came in the form of the portraits of Mao pervasive in China at the time.

“I thought: ‘painting.’”

He had no way of knowing at the time that his idea would lead him down an artistic and spiritual path to becoming a Christian artist admired and respected across China and the world.

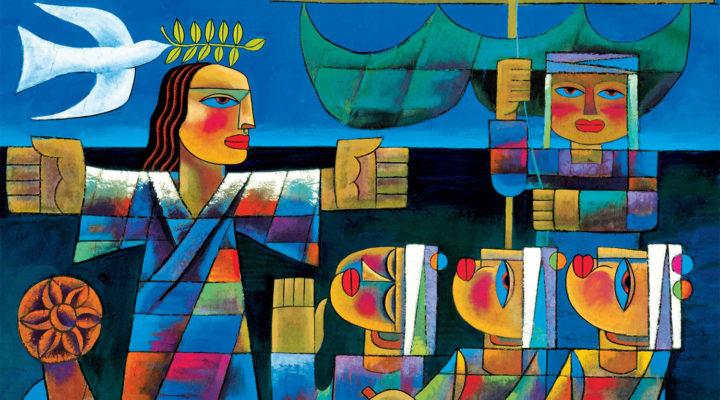

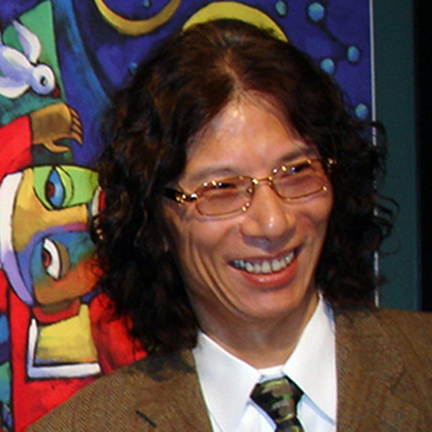

Today, He is artist-in-residence and visiting scholar at the Claremont School of Theology in California. His work was displayed during the Alliance of Baptists’ annual Spirituality Gathering, held this year from Sept. 8-11 near Jacksonville, Fla.

Ken Meyers, the gathering’s organizer and friends with He for 12 years, says the artist used his work to connect spirituality with the work the event’s participants have been called to do.

“He is very interactive and he listens with a real ear for what we’re feeling or sensing,” says Meyers, faith formation specialist for the Alliance. “His goal is peacemaking and his art has all these intersections in it.”

‘In the daytime I painted portraits’

He’s influences are as varied as they are unlikely — and they began in the harsh context of the Cultural Revolution.

Launched in 1966, the decade-long program tore Chinese society apart as Mao attempted to rid the nation of all traces of capitalism and other Western influences. Large segments of society, including intellectuals and urban youth, were displaced and forced into manual labor in rural areas. Cultural and religious centers were closed or destroyed. An estimated 30 million people died in China during the period, many of them from a combination of malnutrition and overwork.

He said he was likely destined to share that fate when an unlikely source of hope appeared: a contest to find artists capable of painting Mao’s portraits. The teen had never painted but he remembered a neighbor in his hometown of Nanjing who was an art educator and paint-er who had studied in Paris.

“He gave me some training and … I was the winner of the art contest to paint Chairman Mao portraits.”

That got him off the farm and onto canvas and “in the daytime I painted portraits.”

It also launched He on an unanticipated spiritual path. Some of the magazines the neighbor lent him to practice drawing and painting contained religious images.

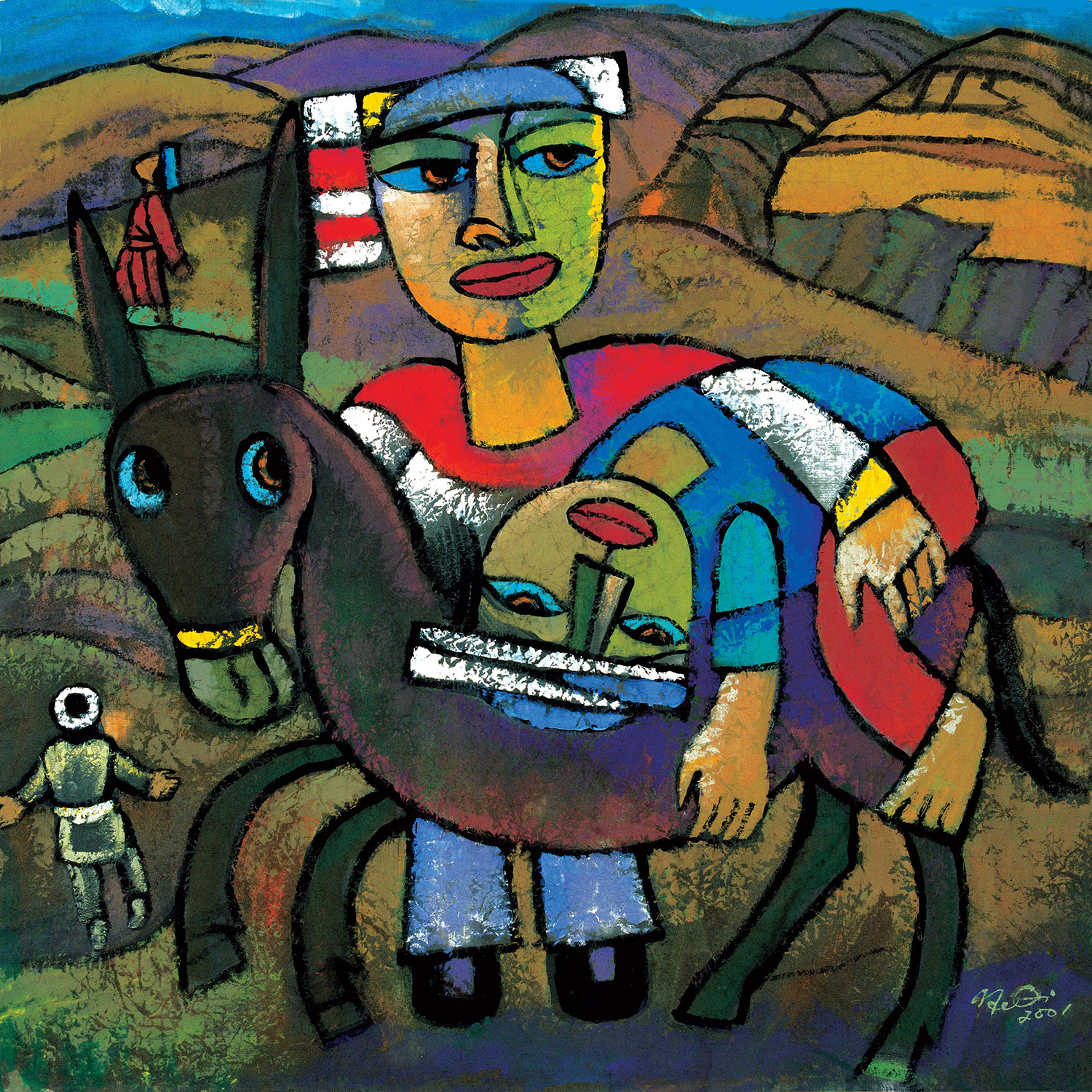

“I remember the covers and one of them showed the Madonna and baby Jesus,” he says. “I was very moved and for the first time felt so peaceful — it touched my heart.”

Not realizing the image was a religious one — which would have been illegal in China at the time — He painted his own version using oils. He remembers showing it to a trusted friend.

“He was surprised and said, ‘You know this is a Christian image?’ I had no idea about Christianity.”

‘I … just wept’

He learned plenty about the faith by the time Anita Snell Daniels encountered him around 2001. She and her late husband, Jack Snell, serving then as Asian mission coordinator for the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, were visiting China. They met He at Nanjing Theological Seminary, where he was teaching.

“I sat at my computer and just wept. I saw Christ hanging on the cross and all these arms reaching up to him.”

Snell Daniels looked up He’s art online after returning home. His painting of Christ on the cross, she says, was overwhelming.

“I sat at my computer and just wept,” says Snell Daniels, a member of Hendricks Avenue Baptist Church in Jacksonville, Fla., where her late husband served as pastor for 20 years. “I saw Christ hanging on the cross and all these arms reaching up to him.”

It was difficult to grasp how someone could use so many artistic styles to convey such focused messages of the gospel, she says.

“He was sharing all of the deep meaning of the Christian faith through art with Chinese symbolism. It’s just amazing.”

It wasn’t long before word got out in American religious circles and He became a regular guest at congregations and seminaries of one denomination or another.

His work has been exhibited at multiple CBF General Assembly gatherings and at similar meetings of other denominations.

He has served as artist-in-residence at theological schools from California to Minnesota, and he is in high demand as a lecturer. His work has also been shown in churches and galleries across Asia and Europe.

But He does much more than display his art, Snell Daniels says. He uses his work, and his survival of the Cultural Revolution, to inspire viewers to seek solace in faith.

“Everything around him has been so hard and so cruel, yet in this state he saw peace and he said, ‘I want to find that kind of peace for myself.’ So he sought out Christianity and that became his quest.”

Expressing a peaceful message

One of the first steps in that quest led him in the early 1980s to Tibet, where he and a team of experts studied and documented traditional wall paintings and frescoes. Their work was displayed in a post-Mao China that was beginning to ease restrictions on art and religion.

The experience influenced He to focus on research into religious art. Back in China and teaching in Beijing, he added Christian art history to his studies.

“I also studied medieval art,” he says, an interest that took him to doctoral studies in Germany.

In Europe, He was exposed to the work of artists like Picasso and Chagall, who also influence his art.

“And I like Chinese traditional folk art, and Tibetan art is also an influence,” he says.

“There are many, many influences in my artwork,” including Zen, Indian Buddhism and traditional Chinese watercolor.

But these eclectic inspirations express a single message of hope — a hope He embraced by becoming a Christian in 1989.

“I can only focus on doing one thing,” he says. “As a Christian artist, I want to express a peaceful message through my artwork.”

His approach has been validated recently, especially in events like 9/11 as well as wars and terrorist attacks which underscore the need for faith-based calm.

“Sharing a peaceful message is most important.”

He says his Christianity is as varied and peace-giving as his painting. Rather than identifying with a particular denomination, he sees beauty in them all.

It’s an approach to faith in part fostered by the Chinese historical and political process. Forced to worship in secret for so many years, Chinese Christians tend to embrace a non-denominational brand of the faith.

So He has no trouble accepting teaching and lecturing invitations from Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans, Presbyterians and others.

“They’re all Christians.”

He’s holistic approach to art and faith are precisely what stressed American Christians need today, Meyers says, noting that He is especially talented at helping practitioners discover the Celtic notion of “thin places” between this world and the next.

At the spiritual retreat in September, He was tasked with “teaching and guiding us in a more mature spirituality and peacemaking mode,” Myers says.

This article was first published in the September-October 2016 issue of Herald, BNG’s magazine sent five times a year to donors to the Annual Fund. Bulk copies are also mailed to BNG’s Church Champion congregations.