As Ukrainian theologian and pastor Fyodor Raychynets serves bread to the elderly imprisoned in bomb shelters, his prayer is to retain his humanity.

“I have to remind myself on a daily basis that we are humans and we are — not just remain — but it is so crucial in the midst of hell, not to lose our humanity. But to preserve it, and to show it, and to demonstrate it. Because that’s what the people need the most at this moment,” Raychynets told Miroslav Volf, a Croatian theologian who teaches at Yale Divinity School.

Fyodor Raychynets

The two men — Raychynets is a former student of Volf’s when he taught at Evangelical Theological Seminary in Osijek, Croatia — spoke on the “For the Life of the Word” podcast that is a product of Yale Center for Faith and Culture. Raychynets is head of the theology department at Ukrainian Evangelical Theological Seminary, located on the outskirts of Kyiv.

Their 40-minute interview offers a rare glimpse into what Raychynets called the “rearguard” of the Ukrainian stand for freedom against the onslaught of war sent by Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

Raychynets, who experienced the Balkans war, says he learned then that in war there is a frontline but also a rearguard. “And in these rearguards, there are so many things to do. So many things to be useful. So we decided that when the war started, we will build a small volunteers group and we will just serve to the people who suffered the most from the war. And these are the elderly people.

“We feed them because they are in the basements,” he explained. “They have no idea what’s going on outside the world. And they’re just there. Blocked. They are scared to death. So many of them could never dream that they will experience a war again in their lifetime. They are there hungry, without electricity, without water. So what we decided to do is we decided just to provide to these people.”

By now, most of the younger mothers with children have been evacuated to western parts of Ukraine, he said, and are hopefully on their way as refugees to Poland and Hungary and Croatia.

Fyodor Raychynets offered fruit and bread to an elderly woman in Urkaine.

The work of the rearguard, he said, is “to provide the necessary things. Medicine, hygiene stuff, clothing, shoes. We don’t supply the weapons or anything like that, but there are many needs beside that to be helpful with. … The rearguard matters a lot to the frontline. And if there are these people, volunteers who are helping with all the necessary things, then the people in the frontline, they feel supported. And they want to protect us. They want to fight for these people and protect us.”

Raychynets and his rearguard colleagues, particularly other clergy, also interact with the military as they pass through checkpoints and enter areas others are not allowed to enter. And in doing so, they have found needs to be met among the forces defending the Ukrainian people.

Last Thursday, Raychynets and two other clergy served Communion to a group of soldiers, an event documented by photos on his Facebook page. Volf asked him: “What’s happening at that moment? What does this communion stand for and symbolize? … What does Christ’s body, given for the life of the world, mean in that moment?”

Raychynets replied: “It was an overwhelming experience for me, because, in the Balkans, I started to believe in what we called an open Lord’s Supper, when everyone is welcomed, and when there is something scandalous in the Lord’s Supper, how it takes place. Because there are always people who should not be there by our theological perspective or our theological beliefs and so on and so forth.

“And when we went there, and, whenever I’m in that kind of situation, and I am to serve the Lord’s Supper, I always ask people — whoever, whatever church they are, or maybe they’re not church people at all — I will come to them with the bread, and I will say, ‘This is the body of Christ broken for you.’ They should just say ‘Amen.’ And I think that whenever they say ‘Amen,’ they agree. That body of Christ was broken for them as well.”

Fyodor Raychynets and fellow clergy serve Communion to members of the Ukrainian military.

As he served Communion to the Ukrainian military members, one of the soldiers appeared to have no religious background, and he asked what all this meant.

“We just said to them, ‘That’s how we do it. We just come to you and we say, “This is the blood of Christ shed for you.” And when he said ‘Amen,’ it was a moving experience. And I believe that we are just the instrument in this kind of situation. And there is a much bigger, invisible presence of God’s grace which can do something that we cannot do.”

Raychynet knows something of brokenness. Not only from the present moment by also from the death of his wife last year due to COVID-19. And now the seminary where he teaches has been bombed to bits and is occupied by the Russians. He does not know the fate of his own apartment or his church’s building.

“We cannot go there. It is now controlled by the Russian troops. But the video footage that we get daily from that city, it looks much worse than Srebrenica. So that’s the condition. Now the frontline goes through the place. Once the most beautiful part of Kyiv, which is northwest of Kyiv.”

Ukrainian emergency employees and volunteers carry an injured pregnant woman from a maternity hospital that was damaged by shelling in Mariupol, Ukraine, March 9, 2022. The woman and her baby died after Russia bombed the maternity hospital where she was meant to give birth. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka,

Volf noted that Raychynet’s name means “the maker of paradise” but he now finds himself in hell.

Volf also commented that Raychynet’s current service to others reminds him of the words from 1 John: “Love conquers all fear.”

To which Raychynets responded: “Yes, I will dare to put John’s statement in different words, which is more relevant to me: It is not that love conquers fear, but it corrects the fear. It challenges your fear.”

And fighting that fear requires fighting to retain some sense of humanity, the Ukrainian said.

“I see how I, myself, am easily overwhelmed with the negative emotions. Especially when we hear some news about newborn children who suffered, mothers in the maternity houses being hit by the missiles. When I see on a daily basis our literally helpless people, who have to suffer because of someone’s obsession with power, with the desire, uncontrollable desire to crush someone’s will. And at some point I am scared for myself.”

Facing this, he must pray “that I would not, in the midst of this hell, lose that humanity.”

Despite the horrors he is seeing firsthand, he tries to offer encouragement on his Facebook posts, “because I don’t want the outrage, the negative emotion, my anger to take control over the situation. Because I think that’s what our enemy wants. And that’s what we cannot let happen.”

Volf commends Raychynet as a person of strong faith, but he demurs.

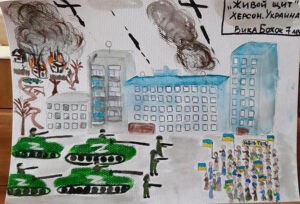

A child’s drawing of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, posted by Fyodor Raychynets to his Facebook page.

“I don’t think I’m a person of a strong faith. I’ve struggled with my faith along the way as a theologian, as a pastor. Because for me, it was always important in theology, in our conviction, to be sincere. Well, to the extent that it is possible. But it is challenging to sustain a faith in the situation where there is a sense that you cannot control anything that is happening. You cannot change anything. You cannot impact on the situation that it would change in the way you would like.

“But on the other hand, I know I will be contradictory, but that’s what theology for me is, very contradicted. … In this situation, when you have control of nothing, when you are laying in your bed and you don’t know whether the place where you stay tonight will be preserved until the morning, and when in the morning you are tired and you don’t want to do nothing, you just want to sit in some safe place, and just even not think to go out. But then you remember these people and you remember their needs, and then you get some phone calls, what they need. And you just trust the Lord that, I will go. And if I die, well, at least I die for the right cause. I was trying to help someone.”

Related articles:

‘The situation here is terrible,’ Ukrainian Baptist leader tells European allies

Mercer scholars explain the immense danger of Putin’s power play in Ukraine