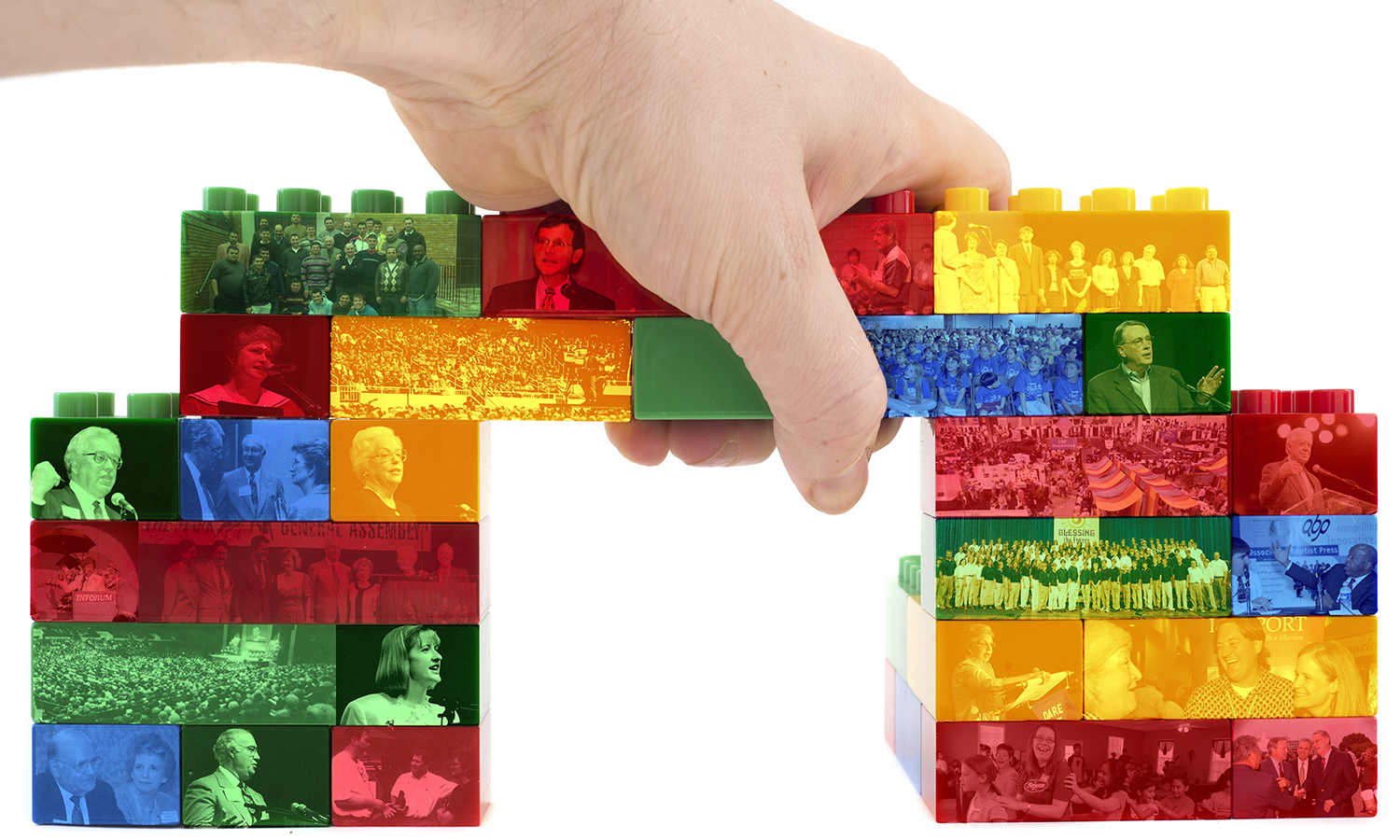

At 25, the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship recalls its birth in a passionate commitment to freedom.

All stories must start somewhere. Baptist stories are no different — from the self-baptism of John Smyth in 1609 to Roger Williams planting the first Baptist church in America in 1639 to the Triennial Convention in 1814 to the birth of the Southern Baptist Convention in 1845. These are just a few beginning points of Baptist stories.

For me, as a writer of Baptist history, the 25-year-old story of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship naturally starts with its little-talked-about founding document — “An Address to the Public,” presented to the group of 6,000 Baptist attendees at the 1991 Convocation in Atlanta where the Fellowship was formalized.

“Forming something as fragile as the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship is not a move we make lightly.” So begins the document, co-authored by Mercer University professor Walter Shurden and Cecil Sherman, who would later become CBF’s founding coordinator. The title itself is an irony of history, named after another “Address to the Public” penned 146 years earlier by William B. Johnson to announce the reasons for the creation of the Southern Baptist Convention. That address formed the SBC. This address formed something new out of the SBC: CBF.

Reflecting on this historic document 25 years later, it is evident that “An Address to the Public” embodied the Fellowship at its best — “free and faithful Baptists” who champion a high view of the Bible, evangelism as well as social justice, women in ministry, ecumenical partnerships, equality between laity and clergy, and a “great and inclusive Church.”

Reflecting on this historic document 25 years later, it is evident that “An Address to the Public” embodied the Fellowship at its best — “free and faithful Baptists” who champion a high view of the Bible, evangelism as well as social justice, women in ministry, ecumenical partnerships, equality between laity and clergy, and a “great and inclusive Church.”

“Being Baptist should ensure that no one is ever excluded who confesses, ‘Jesus is Lord’ (Philippians 2:11),” the historic document said.

“An Address to the Public” also laid the foundation for a Baptist identity rooted in what Shurden popularly described as the “four fragile freedoms” — CBF’s core values of soul freedom, Bible freedom, church freedom and religious freedom. The address grounded the CBF story in a thick freedom theology, united the diverse group of Baptists and helped to usher in a time of togetherness in the early years of the fledgling Fellowship. This was a time to talk, a time to grieve and a time to dream aloud.

Doing ‘a new thing’

Moving forward did not necessarily come easily, however. Decisions were often the product of prolonged debate, but quick progress was made with the adoption at the 1991 Convocation of a constitution and bylaws, a $550,000 budget devoted mostly to funding SBC missionaries, election of a moderator and a 79-member Coordinating Council. Less than a year later, Sherman was named coordinator.

The 1992 gathering — called the General Assembly — saw the election of Patricia Ayres as moderator, the first female and layperson in this top elected position. The first missionaries were appointed and the Fellowship’s first and only resolution was adopted, “A Statement of Confession and Repentance.” Coming on the heels of the 1992 Los Angeles Riots, the assembly publicly confessed and repented of their historic complicity in condoning and perpetuating the sin of slavery. “We reject forthrightly the racism which has persisted throughout our history as Southern Baptists, even to this present day,” the resolution read.

While attempting to do “a new thing” — the Isaiah 43:19-based theme of the founding 1991 Convocation — the Fellowship continued to find itself mired in the deep denominational divisions from which it had sought an exodus, often embracing a protest-movement mindset rather than a future-focused identity.

“CBF was a reactionary movement in the beginning,” writes Bill Bruster, a former long-time Fellowship staff member, in CBF at 25: Stories of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. “We were much more focused on ‘what was wrong with the SBC’ than ‘what is right with CBF.’”

This reactionary approach was rooted in real grief and the pain was palpable.

“Some of us came to the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship rather beaten up,” writes Molly Marshall, a former SBC seminary professor and current president of Central Baptist Theological Seminary, in CBF at 25. “We were tired of being called heretics, skunks, infidels, theologically bankrupt, godless feminists, ad nauseam. We needed a new spiritual home place.”

“Some of us came to the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship rather beaten up,” writes Molly Marshall, a former SBC seminary professor and current president of Central Baptist Theological Seminary, in CBF at 25. “We were tired of being called heretics, skunks, infidels, theologically bankrupt, godless feminists, ad nauseam. We needed a new spiritual home place.”

Like Marshall, many (but not all) desired a new home to do a new thing. As many churches and individuals worked to form a new home place distinct and separate from the SBC, missions solidified its place as CBF’s raison d’etre. A defining moment in this founding period came when Keith Parks resigned as president of the SBC’s Foreign Mission Board and joined the CBF staff as its first Global Missions coordinator. Parks brought instant credibility to the Fellowship’s missions efforts. The focal point of these efforts was strengthening Christian ministry in the former Soviet republics of Eastern Europe, emphasizing the evangelization of unreached people groups, and ministering to internationals in the United States. Dozens of missionaries were quickly hired, with 100 appointed by 1995, including disaffected SBC veterans in addition to newcomers to the mission field.

Forming a freedom identity

As its missions identity took shape under Parks’ leadership, the Fellowship continued to develop during the first half of its history as the movement began to institutionalize with the formation of more than a dozen autonomous state/regional CBF organizations.

Numerous Baptist seminaries and divinity schools were birthed and even more partner organizations started. The CBF Foundation was launched to serve churches and individual supporters with endowment and investment services in 1994 and a detailed mission statement was adopted in 1995. Three years later, CBF received recognition as a non-governmental organization by the United Nations and was allowed to participate in its proceedings. Also in 1998, CBF became a “religious endorsing body” and began endorsing chaplains and pastoral counselors to hospitals and the military, among other specialized settings. The following year an initiative was launched to plant CBF churches and, in 2003, the Fellowship was granted membership in the Baptist World Alliance.

“We can be alone, or we can be in fellowship with other Christians for a compassionate identity.”

While rapidly expanding into an increasingly denomination-like network, CBF continued to cling to its freedom theology. Slowly, the Fellowship began to live — albeit imperfectly at times as supporters and observers alike have noted — into a more holistic theology of freedom, still stressing freedom from fundamentalism but also championing gender equality and other justice issues, ecumenical relationships and interfaith dialogue, as well as a deeper understanding of what it means to be a Baptist in the 21st century.

At the 2001 General Assembly, CBF Executive Coordinator Daniel Vestal, who had succeeded Sherman five years earlier, highlighted this evolving freedom-based identity.

“Our identity and our mission are tied to being Baptist. And being Baptist is not just being a dissenter …. It is being passionate about the free experience of the grace of God revealed in Jesus Christ. It is being committed to the church as a body of baptized believers and then finding ways for believers and churches to connect and cooperate for the eternal Kingdom of God. The longer CBF is a movement of faith and freedom, a grassroots fellowship of churches and individuals, the more we will be an instrument of renewal.”

This attempt to push forward with freedom has been seen in the past 15 years amid attention to justice issues in the Fellowship, including national summits on HIV/AIDS in 2006 and torture in 2008, the adoption in 2007 (and a succeeding sustained emphasis) on the U.N. Millennium Development Goals aspiring to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, empower women, ensure environmental sustainability, and other priorities. In 2013, CBF formalized its advocacy work, concentrating on combating predatory lending, championing immigration reform and advocating for global religious freedom.

A similar emphasis was taking shape within CBF’s missions enterprise under the new organizational vision of “being the presence of Christ.” Following Parks’ retirement in 1999, CBF Global Missions expanded its missiology, focusing on forming sustainable ministries among “neglected” and “marginalized” peoples striving to accomplish community transformation through water projects, disaster response, hunger relief and development projects in rural and urban settings. This asset-based approach is best exemplified in Together for Hope, CBF’s rural poverty initiative launched in 2001 — a 20-year pledge to locally led mission engagement in 20 of the poorest counties in the United States. The last decade has seen the formation of strategies around congregations and their short-term mission teams in partnership with missionaries (called “field personnel” beginning in 2002). More recently, there has been an articulation of the Fellowship’s mission commitments to cultivate beloved community, bear witness to Jesus Christ and seek transformational development.

Seeking a creative ecumenism

Throughout its 25-year history, partnerships and cooperation with other Christians have been a hallmark of the CBF story. The Fellowship declared in “An Address to the Public” the importance of “mending the torn fabric of both Baptist and Christian fellowship.” Seeking to forge a creative ecumenism through cooperative endeavors, CBF’s list of mission partners has been lengthy and noteworthy, from World Vision to Habitat for Humanity to Buckner International to the American Bible Society to name a few. In 2006, Vestal led CBF to become a founding member of Christian Churches Together, a diverse justice-focused ecumenical organization comprised of more than 40 Protestant, Catholic and Orthodox groups.

Relationships with the global Baptist family have been strengthened in the new century through participation in the multifaceted work of the Baptist World Alliance, and joining in the collaborative efforts of the New Baptist Covenant. NBC, regarded as the brainchild of former President Jimmy Carter, has sought to bridge the racial divide between Baptists in North America to live out Christ’s Luke 4 mandate through local churches making “covenants of action” to bring reconciliation and renewal to their larger communities.

“Looking to other rooms of the Christian family,” has been central to the Fellowship’s mission and identity, according to CBF Executive Coordinator Suzii Paynter, who has often emphasized the growing interconnectedness of Cooperative Baptist churches around missions and ministry.

“We can be alone, or we can be in fellowship with other Christians for a compassionate identity,” said Paynter during her first address to the General Assembly in 2013. “You are most likely the Baptists in hundreds of communities that show up for ecumenical, interdenominational and interfaith collaborations. Our willingness to hold our convictions strong and yet be generous in friendship is what makes us stand out.”Focusing on theological education

Support for theological education and an intentional focus on young Baptists are areas where the Fellowship has been most impactful — contributing significantly to the diversity of viewpoints within the “Big Tent” that has characterized the Fellowship. Since 1992, CBF has provided scholarships to more than a dozen partner theological schools and in the second half of its history has launched several key initiatives to nurture the callings of young Baptists through retreats, a collegiate congregational internship program (Student.Church) and sent hundreds of students around the world to serve alongside its field personnel (Student.Go).

Support for theological education and an intentional focus on young Baptists are areas where the Fellowship has been most impactful — contributing significantly to the diversity of viewpoints within the “Big Tent” that has characterized the Fellowship. Since 1992, CBF has provided scholarships to more than a dozen partner theological schools and in the second half of its history has launched several key initiatives to nurture the callings of young Baptists through retreats, a collegiate congregational internship program (Student.Church) and sent hundreds of students around the world to serve alongside its field personnel (Student.Go).

“It has been in theological education where the Fellowship’s partnering with new seminaries has been transformative,” writes Vestal in CBF at 25. “These schools … have changed the face of Baptist life. Their influence and impact are truly remarkable.”

The focus on young Baptists was instrumental in forming the Fellowship’s identity, notes Paynter. “It gave us something to focus on, rather than focus away from and that would not have been possible if we didn’t have these seminary connections.”

“When CBF contributes scholarships to seminarians, they are literally investing in the future,” adds Bill Leonard, professor and former dean of Wake Forest University School of Divinity. “These are students and now graduates who are choosing Baptist life, who are choosing to be involved in CBF. They don’t have the old networks, they don’t have the old histories, but they are energized. I am in awe of them for the commitments they are making to pastoral ministry and Baptist identity.”

Embracing egalitarianism

Perhaps the most significant development in CBF’s quarter-century history has been its unequivocal embrace of women in ministry as a cornerstone commitment. That embrace has certainly come slowly and there remain more stained-glass ceilings left to break. While there were only 51 women serving as pastors in the SBC in 1993, there are now at least 119 women pastors and co-pastors in the Fellowship, according to a new “State of Women in Baptist Life” report by Baptist Women in Ministry.

BWIM Executive Director Pam Durso has described 2015 as a “banner year” for women being called as pastors. “In the last few years, more and more CBF churches have been intentional in including women candidates in their pool, and then in 2015, a record number of churches called women pastors,” Durso says. “The slow but steady progress that has been made gives me much hope for the Fellowship’s future. But the daily emails and phone calls that I receive from women who are struggling in their search for ministry positions remind me that the work is nowhere near finished.”

At the still-young age of 25, CBF — with its freedom-based identity in tow — is well positioned for the next 25 years, ready to keep living into its values and ready to keep doing “new things” together.

“Cooperative Baptists have a unique identity that our world needs,” writes Marshall. The kinds of freedom and gospel accountability that define our story are good news, truly. … The spirit works in freedom, calling the church and society to new forms of service in the world. In a day when participation in congregational life is in rapid decline, freedom-loving Baptists must make a compelling case for the role that the gathered community plays as a transformative agent of the Spirit.”

This article was first published in the Summer 2016 issue of Herald, BNG’s magazine sent five times a year to donors to the Annual Fund. Bulk copies are also mailed to BNG’s Church Champion congregations.