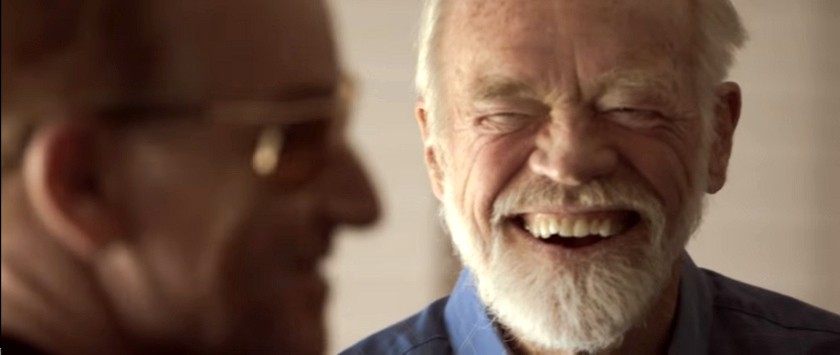

Some of Winn Collier’s most cherished moments with the late Eugene Peterson include sitting quietly with the pastor, author and translator of The Message Bible in his Montana home overlooking Flathead Lake and the Mission Mountains in the distance.

“When you were with Eugene for extended periods of time, there were often these long periods of silence that at first seemed awkward but became holy and beautiful. That was just a holy space,” said Collier, director of the Eugene Peterson Center for Christian Imagination at Western Theological Seminary in Holland, Mich.

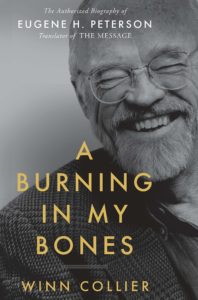

Collier shares more of those memories in his latest book, A Burning in My Bones: The Authorized Biography of Eugene H. Peterson, Translator of The Message, which will be released later this month.

Collier shares more of those memories in his latest book, A Burning in My Bones: The Authorized Biography of Eugene H. Peterson, Translator of The Message, which will be released later this month.

Collier, former pastor and founder of All Souls Church in Charlottesville, Va., spent years conducting interviews and poring over journals, personal letters and photos to help readers know a man many considered to be America’s pastor.

“I hope people feel like they actually encounter Eugene and enter into his world,” Collier said of his book.

By the time Peterson died in 2018 at age 85, he was known to much of the world as a prolific author who penned more than 30 books, including The Contemplative Pastor: Returning to the Art of Spiritual Direction, The Jesus Way and The Message, his 2002 translation of Scripture from Greek and Hebrew into everyday English that has sold more than 15 million copies worldwide.

Eugene Peterson

Peterson, a Presbyterian pastor for more than three decades, also was a keen observer of the state of the church. He lamented the rise of the megachurch phenomenon, online worship and the church-as-business approach to ministry.

Those and other concerns derived from his primary calling as a pastor intent on making Christ, the Bible and discipleship intensely practical to members of his church and his audience of readers, Collier recalled.

He often was wary of gauging ministry success by financial and membership growth. “While he found that many of those things are necessary at times, they were often driven more by an American entrepreneurial and capitalist spirit than the ancient work of being a pastor to God’s people,” Collier explained.

For Peterson, a pitfall of such methods included becoming trapped in them. “Church doesn’t always work or run smoothly, and you can’t always measure success in that way. He said if Jesus’ life tells us anything, it’s that ministry may not be successful at all and it may get you killed.”

Peterson avoided theological abstractions and promoted the idea that “pastors must immerse themselves in the lived conditions of their people. You have to attend to the story of the people you are with.”

That sensibility inspired a project that eventually led to The Message, Collier said. Years earlier, Peterson translated sections of Galatians for members of a Sunday school class that had been struggling to follow along as he taught.

“You have to attend to the story of the people you are with.”

Members of his congregations loved the translated passages so much that Peterson later included them in a book and the publisher suggested a wider translation, Collier said. “It’s important to understand (The Message) didn’t start out as ‘I’m going to translate it for the world and America.’ It was just for this little circle of friends at church.”

That’s another illustration of how Peterson approached people and ministry. “His question wasn’t ‘How do you build a leadership pipeline?’ It was, ‘How do I teach people to pray?’ That was the important question for Eugene.”

His concern about the megachurch, in turn, was that it represented the church being overrun by cultural forces and business practices that have little to do with the kingdom of God, Collier recalled. “And the danger of that for Eugene is that the church becomes anti-relational. He didn’t see how the constant fascination with getting larger and larger contributes to being relational. He thought it was a betrayal of that.”

Peterson also cautioned against over-reliance on the logical mind to view Scripture and God. Imagination was a key to that understanding, Collier said. “Eugene used the word ‘imagination’ not to mean ‘to make things up,’ but as the capacity to see spiritual things we usually miss with the didactic, rational mind.”

Peterson’s journals were filled with biblical allusions connecting his experiences with those described in Scripture. “He would say, ‘I have to cross my Red Sea’ or ‘I have to cross my Jordan,’” he said. “He wasn’t using the Bible to illustrate his life, but he was seeing himself in the Bible’s world.”

Peterson’s reading lists were heavy in poetry and fiction “because they created worlds of possibilities you can’t see by purely rational means.”

As a result, Peterson’s reading lists were heavy in poetry and fiction “because they created worlds of possibilities you can’t see by purely rational means,” Collier said. “He believed that to see God and grace as they really are requires a new way of seeing.”

That way of seeing, in turn, attracted many creative people to Peterson and his writings. “A lot of musicians and painters were just really drawn to him because, like him, they didn’t see the world as separated and siloed.”

Bono listening to Peterson

One of those artists was Bono, lead singer of the rock band U2. He reached out to Peterson after reading the author’s book Run with the Horses: The Quest for Life at Its Best.

“He found in Eugene a really faithful Christian voice speaking a language that Bono recognized. He was drawn to Eugene’s wide, expansive imagination and to the way he interpreted Scripture. … After that, Eugene became something of a pastor to Bono as their relationship continued.”

Peterson’s mother also helped shape his imaginative foray into the life of the Spirit. A Pentecostal lay preacher, she took him as a boy to preaching events at grange halls and logging camps. “Her faithfulness and her passion for God and her love of people really formed him a lot,” Collier said.

Perhaps that’s why, shortly before his death, Peterson seemed to have his fill of the nasty political and cultural climate that erupted during Donald Trump’s presidency, Collier noted. “One of his favorite rituals was reading the newspaper with his coffee. But at some point, he canceled his paper subscription because he couldn’t stomach reading about Trump anymore.”

This wasn’t just a political issue for Peterson. “He was absolutely bewildered. He could not comprehend how President Trump seemed to have seduced such large portions of the church.”

Peterson’s response to these and other challenges included running, woodworking, memorizing portions of the Psalter, checking in with his Carmelite nun spiritual advisor “and just putting one foot in front of another.”

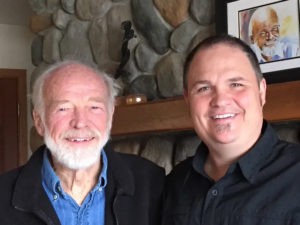

Eugene Peterson (left) with Winn Collier

Collier said writing the book and his years-long friendship with Peterson significantly changed his own life. “In 1999 I read his book Working the Angles. It just smote me. It’s where I saw what it means to be a faithful pastor in our time.”

They later were introduced by a shared publisher and began exchanging letters. “From that back and forth he became like a pastor to me.”

The goal of the biography is help others find a similar connection with Peterson, Collier said. “My hope is that people will encounter the reality of Eugene and feel like they have met him.”