I’ve been engaging in hard conversations about race for the past seven years. Sometimes I’m asked if they matter, if anything can change hearts and minds.

Not long ago, a friend who is a devout Christian and a person of genuine good will wondered if I was wasting my time, people being what they are, believing what they do.

James Baldwin

There’s so much anger, so much division. Why bother talking?

Here’s what I’ve been thinking about lately:

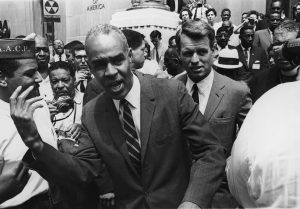

In May 1963, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy asked James Baldwin to gather a group of Black artists and advocates to meet with him and Department of Justice lawyer Burke Marshall in his Manhattan penthouse. Baldwin invited a number of people involved in the fight for racial freedom, including Harry Belafonte, Lorraine Hansberry and Lena Horne.

Kennedy wanted to lay out the racial accomplishments of the John Kennedy administration, to explain the political realities of why change moved so slowly, and to try to understand the rage and despair among Black people when — as he felt — things were changing for the better.

He seems to have imagined this meeting in his family’s apartment off Central Park as following a familiar and comfortable formula: A powerful white man explaining how things were, a Black audience nodding their heads and perhaps offering some words of thanks or confirmation or encouragement.

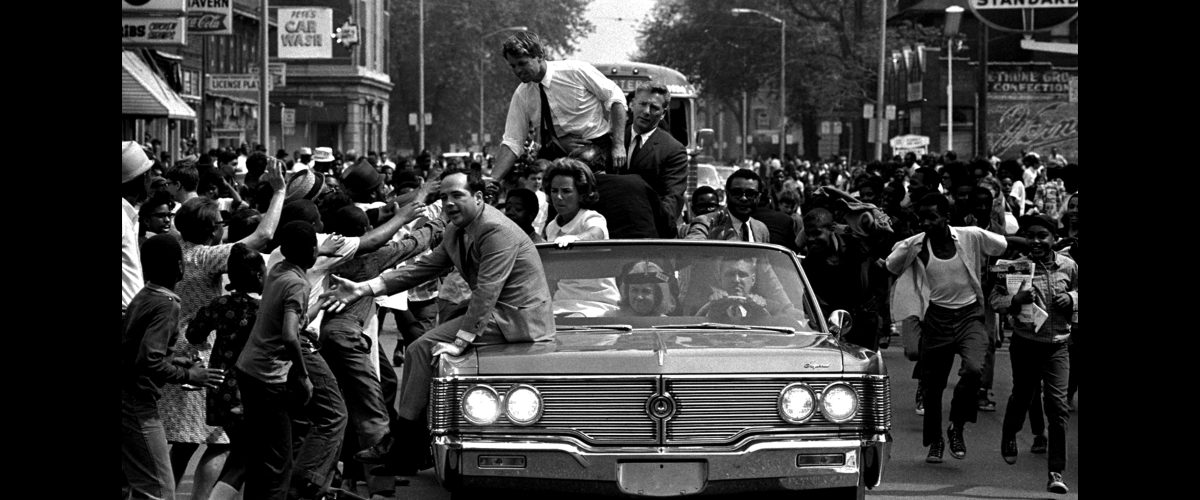

Jerome Smith’s Jackson, Miss., police mug shot, taken after a 1961 arrest.

But Jerome Smith, 24, who had suffered horrific personal violence working as an activist in the Deep South, departed that script. After listening to Kennedy extol the accomplishments of the administration and discuss the political problem of racist Southern Democrats, Smith told him he didn’t know why he was there listening to “all this cocktail party patter.” He told Kennedy he had reached the outer edge of his strength and his patience, and although he truly believed in nonviolence, he could not promise to keep turning the other cheek if the police kept coming at him with dogs, billy clubs, and firehoses.

“When I pull a trigger, kiss it goodbye,” Smith said. Then he shocked Kennedy further by telling him that young Black people fighting for their rights at home would not fight for this country in Vietnam or anywhere else. Why should they?

Kennedy and his older brothers had served in World War II; Joseph had been killed, John badly injured. RFK turned away from Smith, startled and angry, and scanned the room. Was there a more civilized voice, someone who could hear reason, anyone who understood political realities better than this boy?

But playwright Lorraine Hansberry turned the attention back to Jerome Smith: “You’ve got a great many very, very accomplished people in this room, Mr. Attorney General, but the only man who should be listened to is that man over there.”

The evening ended badly. Hansberry coolly told Kennedy good night and walked out, and the others followed. Kennedy felt ambushed and angry, and he lashed out against Baldwin, Hansberry and Smith in the press.

Historian Larry Tye writes that “neither side got what it wanted. The Blacks had grasped the chance to vent their rage — one reason they’d come on such short notice. They had also hoped to remake this well-meaning brother of a president into an ally, not for his incremental reforms but for breakthrough change. The Blacks believed they had not only failed but that they had burned the bridge they had come to build.”

“Robert F. Kennedy had gone into this hard conversation with Baldwin and his cohorts as a well-meaning white man who assumed he knew what was best.”

Robert F. Kennedy had gone into this hard conversation with Baldwin and his cohorts as a well-meaning white man who assumed he knew what was best and that his country was on an upward trajectory in regard to race. He was a good white liberal. But what he encountered was the truth: Black people were weary and angry and in despair because this nation denies the moral reality of racism. Even many good white liberals.

Kennedy was incensed and outraged in the moment and for some little time after. But to his credit — and to my friend’s question — something shifted in him after that conversation.

In Christian teaching, we often refer to the New Testament Greek word metanoia, typically translated as “repentance.” In the church of my youth, that was the important idea: Stop doing those bad things you shouldn’t be doing. But the actual meaning of the original Greek is more nuanced; it’s not simply about stopping what you shouldn’t do, but about a 180-degree turn toward what you should do. Stop doing these bad things, and lean into these good things. As Baldwin believed, we can always be better.

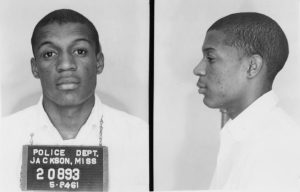

Mark Whitaker noted in the Washington Post that Bobby Kennedy “was one of the rare leaders in our national history who appeared to grow wiser, humbler and more compassionate the more fame and power he attained.” Only a few weeks after being confronted with uncomfortable truths at Baldwin’s civil rights meeting, Robert Kennedy was the lone adviser encouraging JFK to take the politically risky step of responding to Alabama Gov. George Wallace with a substantial speech on civil rights.

RFK and Burke Marshall actually worked with speechwriter Ted Sorenson on the speech the president delivered on national television on June 11, 1963. Bobby also sat with his brother in the minutes before he went on air, helping him script additional talking points.

NAACP executive secretary Roy Wilkins (1901 – 1981) walks in front of U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy (1925 – 1968) during a NAACP march in front of the Justice Building in Washington, D.C. in 1964. (Photo by Washington Bureau/Getty Images)

Eric Michael Dyson has said that Baldwin and the others in New York had wanted Bobby Kennedy to realize that the question “was not just about politics; it was about morality, dignity, about taking a symbolic stand in front of the entire country. Kennedy didn’t get that. He kept insisting that change was hard and slow.”

But the speech John Kennedy delivered that night shows that those lessons were not wasted, how that hard conversation had led to some hard reassessments. JFK went further than any previous president in calling out racism as a national sin:

We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the Scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution.

The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated. If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, if he cannot send his children to the best public school available, if he cannot vote for the public officials who will represent him, if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place? Who among us would then be content with the counsels of patience and delay?

By describing racism as a “moral crisis,” Kennedy said that even though there must be constructive political action, this was, at heart, a question about what sort of nation America would be, an issue to be decided in every American heart — language very much like Baldwin’s frequent argument that how America handled the race question would determine whether the American experiment would succeed or fail.

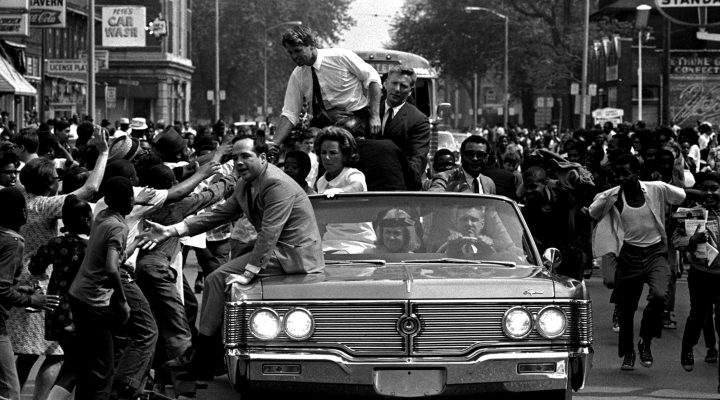

In the years following that painful cocktail party, Bobby Kennedy demonstrated a love and understanding for the poor, for the downtrodden of every race, and for those held down by white supremacy. As a senator and as a candidate for president, Robert F. Kennedy showed how hard conversations could change the people involved, how the “witness” Baldwin often spoke of could bear fruit.

This is far from the only story about conversation leading to engagement, of course, but it’s one of my favorites. So to my friend — and to all of us — I would say: Hard conversations matter, perhaps more than ever in a radically divided nation. They’re only a first step. But until we take that first step in faith, until we are willing to sit with possible discomfort, the rest of the journey remains out of reach.

May we risk something big for something good.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett is Carole McDaniel Hanks Professor of Literature and Culture at Baylor University and canon theologian for The American Cathedral in Paris. One of America’s leading voices on religion and culture, he is the author of more than two dozen books, most recently In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is currently administering a research grant on racism from the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation and writing a book on racial mythologies for Oxford University Press. Greg is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church and canon theologian at the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.