In Central Florida this summer, the sounds at Lake Yale Baptist Conference Center resembled more a Quaker retreat than a rambunctious camp for teens yelling at the tops of their lungs.

There was no frolicking in the lake or singing around campfires. Camp Director Jeff Yant likened it to more like the sounds of silence than “Kumbaya.”

For decades, a week or two in a rural location has been much-anticipated time on the calendar for Protestant church life in America. Church homecomings, youth camps, even revival meetings centered around the auditoriums and campfires of retreat centers. This year’s pandemic changed all that, though, as camp directors sought ways to accommodate smaller groups with more intense health hygiene.

Jeff Yant

As the nation eclipsed 110,000 COVID-19 deaths in early summer, congregations became far more cautious about putting the health of their members at risk for a summer in the woods. In the 12 weeks between June 6 and the week leading up to Labor Day Weekend, another 70,000 deaths were recorded, bringing the national total to slightly more than 180,000.

With nearly 6,000 weekly deaths nationally during the summer, it was no wonder families were staying close to home and avoiding groups of strangers in conference center settings. Parents felt validated for keeping their children home after the virus spread to 260 campers at a mask-less YMCA camp in Georgia.

Baptist camps and conference centers have been especially hard hit by the pandemic.

Yant walks around the grounds of Lake Yale, contrasting the silence with the usual cracks of a baseball hitting a bat or the whining of a zip line through the trees.

“Summer is typically our big season and we are usually full, with up to 800 campers,” he said. “It’s kind of eerie to walk the grounds and see empty fields and empty buildings. It’s not unusual, due to the pandemic, for us to go three weeks with no one and then have a small group of 50.”

Quick adaptation at Ridgecrest

At Ridgecrest Conference Center, a legendary Baptist retreat in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, the scene has been much the same. After mass cancellations in mid-March and as group gatherings were banned based on public health concerns, the leadership team at Ridgecrest began to brainstorm how to save the summer — and generate badly needed revenue.

A promotional banner for Ridgecrest.

The solution was to pivot from summer camping to socially distanced family retreats. That format proved to be a popular option for parents still feeling the need for a family vacation in a setting they could trust.

At Ridgecrest, parents and their children rotated between the two summer camps normally reserved for boys and girls and the main conference center facilities, enjoying a smorgasbord of swimming, hiking, a rock-climbing wall, and other amenities.

And, of course, the ever-popular ice cream parlor, which has been the evening focus for decades. The difference this year was that there were no crowds spilling out of Spilman Auditorium after hearing a guest speaker who challenged them in their faith.

Ridgecrest Executive Director Art Snead and staff seized on the idea of extending the family retreat idea, which traditionally occurred only on Labor Day weekend, to the nine weeks of summer. Marketed as “Family Getaways,” these packages provided an all-inclusive experience with lodging at either of the camps or the hotel.

“Families could stay for a minimum of three nights or however longer they desired, as a family unit with no intermingling with other guests,” Snead explained. “They might spend the morning at the girl’s camp pool or move over to the boy’s camp for different activities. They were able to enjoy swimming, axe throwing, archery, a climbing wall, rope swing, zip line, and lake activities at their leisure.”

All in a socially distanced environment with the facilities sanitized between groups.

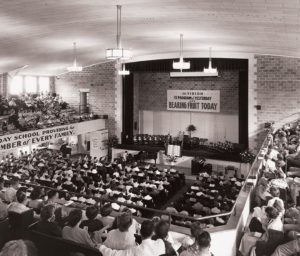

Spilman Auditorium at Ridgecrest was built in 1938. The original auditorium had a seating capacity of 2,600. (Ridgecrest photo)

More than 400 families participated between mid-June and Aug. 2, allowing the facility to keep all 85 full-time employees on staff. The original event, called “Endless Family Adventure Weekend,” is still scheduled for this Labor Day weekend.

While the primary conference center remained open for small groups, the emphasis this year fell on small groups. Ridgecrest continued to host individuals on a personal spiritual retreat or ministerial getaways, plus a few very small events.

“We did whatever was safe within government guidelines,” Snead said.

Still, the facility was far below its 2,000-person capacity all summer.

Before the pandemic, business had been good for Ridgecrest, with an increase in guests over the past seven years. In 2013, the ministry hosted 59,000 guests, a number that had grown to 65,000 last year. By the end of February this year — days before the extent of the pandemic became known — Snead was anticipating a strong year in attendance and income, with bookings ahead yet again.

Snead credits the facilities’ steadily booming business with its investments in infrastructure.

“We have very strong Wi-Fi in the conference center and can stream events for those unable to attend live programming,” he said. “We have invested especially heavy in technology for sound and audio-visual capability in Spilman Auditorium.”

The next chapter for Ridgecrest, as for all conference centers, will be determined by the nation’s ability to accept face masks and social distancing until a vaccine can be produced.

“Tremendous shortfall” in Georgia

At the Georgia Baptist Conference Center at Toccoa, the problem is slightly different.

Bill Wheeler

Director Bill Wheeler said 2020 was forecast to be his camp’s strongest year ever. A full house was booked for a weekend in mid-March but emptied out group by group as the virus spread.

“We lost the majority of our bookings … popular youth gatherings like Impact, SuperWow, Surge were all cancelled in June. Quilting retreats, family reunions … they were all cancelled, about 152 groups total,” he explained.

Wheeler added that the 985-acre property will post “a tremendous revenue shortfall this summer, and our fall months are not looking much better. October is usually a very strong month in northeast Georgia for senior adult retreats with prominent speakers and musicians, but we are losing many of those due to their at-risk factor,” he added.

“We hosted a wedding party and some pastors, but overall it’s been a very quiet summer. We never closed and have the facility to host anyone, there just hasn’t been any demand.”

Part of the Toccoa facility’s problems is how the state opened up aggressively to stimulate the economy. Ahead of most other states, Georgia bars, restaurants, bowling allies, tattoo parlors and hair salons were the first to be given the green light to reopen as long as customers practiced social distancing.

Gov. Brian Kemp flew around the state requesting residents wear masks but only if they were comfortable with the idea.

By mid-August, Harvard University and Georgia Tech University released separate reports identifying Georgia as the most likely place in the nation to contract the virus.

While Stephens County, where Toccoa is located, is not a high-risk area, groups from around the state thought twice about attending a retreat where others from high-infection areas might also be on campus.

Dining hall at Georgia Baptist Conference Center in Toccoa

Conference center directors like Wheeler stressed that they strictly follow health guidelines suggested by the CDC and other government agencies. They can encourage following proper safety standards, but they primarily provide the facilities and host guests; each group is responsible for implementing social distancing while on campus, especially when children and teens are involved.

Wheeler, like other conference center directors, said these guidelines extend to the dining hall. Mealtime is booked for groups so there is no mingling with other guests, and buffet lines have been modified to allow guests to indicate what they want and staff plate the food for them.

“This summer is nothing like I have experienced in my 25 years here at Toccoa,” he added. “What I have reminded our small staff is that we live by the wonderful gift of today. We do our best and give our best today as a gift from the Lord and just not worry about tomorrow.”

Crickets at Falls Creek too

In the Arbuckle Mountains of Oklahoma, Andy Harrison knows well the eerie sounds of silence. It’s somewhat deafening as he hears the wind blowing across the campus of Falls Creek Baptist Conference Center.

Andy Harrison

Harrison walked into a budgetary buzzsaw just 14 months after being named the director of the historic Baptist camp in January 2019. In a matter of weeks this spring, enrollment at Falls Creek — known as the nation’s largest youth camp — collapsed under the strain of the pandemic.

In early spring, leadership at the Baptist General Convention of Oklahoma cancelled all summer children and youth camps. LifeWay Christian Resources followed with their summer collegiate programming. Indian Falls Creek, the largest national family gathering of Christian Native Americans for more than 75 years, cancelled its July meeting with 2,500 guests and moved online.

“Basically, we were closed for the summer,” Harrison said. “We had a very few number of small groups staying in individual cabins to avoid contact with others. The summer has been pretty much a wash.”

Traditionally, Labor Day begins the season when Falls Creek starts hosting smaller gatherings when the weather begins to cool. But this year, bookings are slim to none with just a handful of church events on the calendar for now.

The camp’s website shows that the Singing Churchmen Retreat, set for Sept. 21-22, has been cancelled. But the annual Fall Back Weekend, which attracts up to 1,900 collegians, is still set for Oct 16-17. Harrison expects attendance to be lower based on how the opening of college campuses plays out. Registrants will be notified no later than Oct. 5 if the event is cancelled.

The modern worship space at Falls Creek is a far cry from the historic open-air Tabernacle used for many years.

Falls Creek usually hosts between 80,000 and 90,000 guests throughout the year. When asked what this year’s enrollment would be, Harrison paused for a moment, then jokingly responded “Probably nine.”

Then he began a quick tally off the top of his head, starting with the big Youth Evangelism Conference that was held before the pandemic hit and checking off cancelled events too numerous to count. He paused again with a more somber tone in his voice.

“I’d say we will end the year with between 4,000 and 5,000. That’s a pretty good drop, anyway you look at it.”

Winter is coming

Christian camps and conference centers make most of their money in the summer months and then scale back on staff in the off season. But this year the scaling back began in March, and the lack of cash flowing in throughout the summer, will make winter harder to bear.

At Shocco Springs Baptist Conference Center near Talledega, Ala., Executive Director Russell Klinner saw the clouds building in mid-February and thought to himself, “This is going to get bad before it gets better.”

By April, he was bracing for a 50% drop in income. To avoid that cliff, the seasonal staff headcount of 180 was reduced to 100. The government’s Paycheck Protection Program through the CARES Act supported the ministry through those months with no cash flow.

By June, payroll for the high season had been decreased to 36 full-time cross-trained workers. The end of July saw a summer full-staff payroll bumped up to 150 workers but still below the normal 250.

“It was a strange summer. It was not unusual to book five groups and then cancel just as many before the day ended,” Klinner said. “Most were just not comfortable with the risk.”

By May, cancellations had erased $1 million from the camp’s income budget before the first campers arrived in mid-June. In August as the summer drew to a close, the pandemic had erased $4 million from the budgeted guest income of $5.5 million.

Fortunately, Shocco Springs will survive due to having stored away financial reserves from past years. A $2.5 million chapel construction project will be delayed, and a major update of the air conditioning in the main conference building has been put on hold.

Other camps may not be so fortunate as the winds of winter blow in.