Talk of civil war is bandied about by Americans reeling from a pandemic, racial injustice, police brutality and a hate-filled election season.

Harold Tessendorf as an official with Habitat for Humanity. (Photo/Courtesy of Harold Tessendorf)

But politically motivated violence is no idle talk to Harold Tessendorf, a conflict management consultant and licensed mediator who honed his peace-building skills in his native South Africa during the tumultuous and bloody period that ultimately ended apartheid.

Now a member of First Baptist Church of Christ in Macon, Ga., Tessendorf witnessed the power of dialogue in either preventing violence or healing from it.

Today, he is passionate about spreading that message to American churches since their South African counterparts were essential to bringing about reconciliation.

“This what the churches are called to do: to build bridges,” he said. “This is long-term work. But it’s when we build those skills and relationships that we can start to talk about the hard issues.”

Tessendorf spoke with Baptist News Global about the lessons he learned in South Africa and how they may help in the U.S. during troubling times.

How did a man from South Africa come to be a Baptist in Georgia?

At the end of 1994, I had the opportunity to work in Haiti. This was after the United States had intervened there to reinstate President (Jean-Bertrand) Aristide as the democratically elected president of Haiti. And during that time, I met the woman who would become my wife, who was from the United States.

After we were married, we worked in different parts of Africa. I headed up a British NGO in Mozambique, and when that contract ended, we returned to the United States. I had seen the work of Habitat for Humanity, and that started a roughly 29-year career with various Habitat affiliates in Georgia. We worshiped in different churches, but we ended up at First Baptist Church of Christ in Macon because I knew some Habitat board members who were members of that church. We enjoyed it, so we stayed.

What church were you raised in?

I was raised Lutheran. My family has been Lutheran for generations going very far back.

What are the major faith groups in South Africa?

In terms of Christian denominations, Anglicans and Methodists and to a lesser degree Presbyterians. Lutherans are there as well. And then, of course, you have a lot of Reformed churches, particularly those that come out of the Netherlands and the Afrikaner movements. You also have a tradition of indigenous African churches. They are very strong.

Are other faith groups present?

Islam has a significant presence. It goes back to when the Dutch initially settled in the Cape and brought in slaves from what is today Indonesia and Malaysia. And there are people from the Indian subcontinent brought in by the British in the 1800s. Among that population you have Hindus. South Africa is definitely a multi-faith country. But during the apartheid era, the predominant faith would have been Christianity.

How did you become a mediator?

During my undergraduate studies, in the 1980s, the political violence in South Africa between the apartheid order and the liberation movements was heating up and putting pressure on South Africa. At this time one of my professors received a grant and he said surely there’s got to be another way out of this. How is this going to end? Is there another way than just brute force? So, he helped establish, at what is now Nelson Mandela University, an institute focused on conflict resolution. I started out as a student worker in that.

Later, I started getting selected for (conflict resolution) training events, and that’s where I began to be at some of the church-based centers where I was trained as a mediator. Then a position became available; I became the director of one of the regional peace committees from 1992 to 1994.

What organization were you involved with?

People outside of South Africa, when they hear about reconciliation, they think of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was co-chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu. It was established after the first democratic elections were held in 1994. It provided an opportunity for both the perpetrators of violence and the victims of violence to tell their stories and for some reconciliation to take place. It was so people could really understand what happened in those murky times. The incentive for the perpetrators was that they would be granted immunity for the often-heinous things they had done. But it was also an opportunity for victims to be heard.

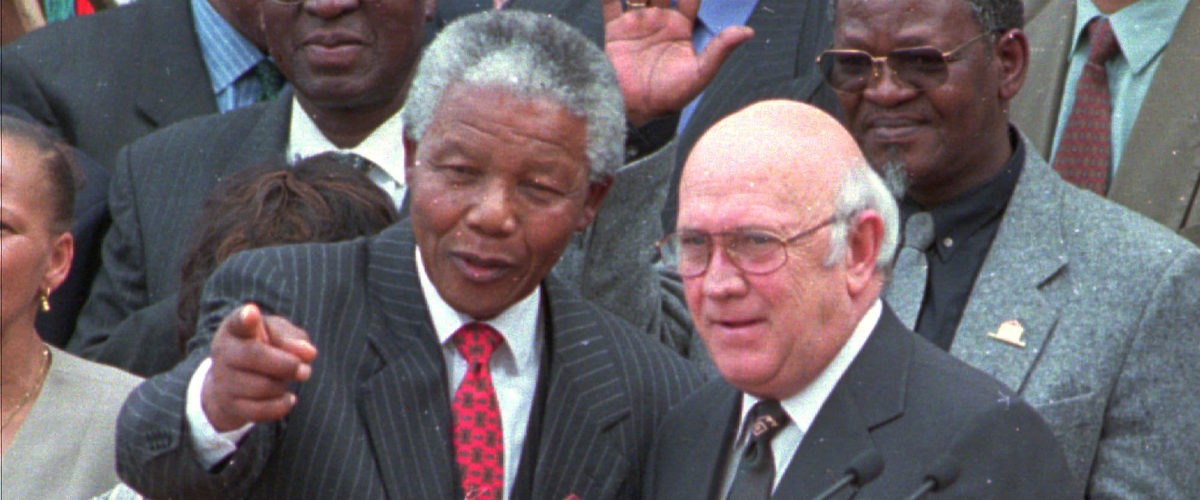

My group was the National Peace Accord. In 1990, F.W. de Klerk announced the unbanning of the ANC (African National Congress) and release of Nelson Mandela. There was talk of a negotiated transition, but everyone was gunning for power. The relationship between those political leaders was never a good one. And there were elements in the police and the military who were right wing and did not want to see a negotiated, democratic South Africa. They were using violence to destabilize the negotiating process.

So, in 1991, church and business leaders got together and said this can’t continue. And they began to lobby and pressure the political leaders to agree on a process to prevent violence and respond to flashpoints in order to keep the peace while these negotiations were taking place. They put together this National Peace Accord in 1991.

How is the racial and political context of the U.S. today like South Africa at that time?

I think they are similar in the sense that people are more and more in their bubbles. I’ve heard the term “echo chamber” used. We only hang out with people, and talk with people, who hold similar viewpoints. I see more of that divisiveness and more of the dehumanizing of people that I saw in South Africa.

In some ways I think that’s where the role of our faith comes in. If we say we are all created in God’s image, then dehumanizing somebody presents us with a challenge.

And there is also a lot of fear. My concern has been that things are starting to spiral out of control. If we don’t get the results we want, our rhetoric becomes more hardline. Just below that, we see more and more of this question of weaponizing the conflict, whether it is with physical firepower or the use of social media.

There is a sense of pessimism in the U.S. about whether dialogue can work in this context. Did you see that attitude in South Africa at the time you were working there?

The answer to that is, yes. But I strongly believe, as a matter of faith, that death never has the last word. Hope does. Growing up in South Africa as a young person, my generation did not feel very hopeful at all. We felt we were caught up in a cycle of violence we could never escape from. But we were able to overcome that because we realized we had to sit down and talk.

At the time when the tensions were starting to increase, people were starting to talk. That’s where business groups and faith leaders were so important. They legitimized the reconciliation process, and they kept those doors open. And if it can be done here, the church must keep that dialogue open. There is a strong tradition in the Gospels. Jesus may have disagreed with a lot of people, but he talked to them. That’s our model.

But does it take widespread violence to create the motivation to engage in that process?

Waiting for violence to increase to that point is a very dangerous strategy because it emboldens those who believe you can never talk. The important thing is to start building those bridges beforehand. That doesn’t mean you won’t have violence, but there is a better chance conflict will not escalate out of control.

We should be building those relationships between (liberal and conservative) pastors and congregations. We should be building relationships with local law enforcement and with groups in other sectors we don’t have relationships with.

We should be investing in developing problem-solving skills. The lesson from South Africa is that by getting those skills of mediation and facilitation into the hands of more people, we can build more bridges and hope.