Pastors in the United States continue to feel increasingly exhausted, isolated and uncertain of their place in ministry in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Barna reports in a new study on clergy resilience.

Barna said its research “shows that pastors’ confidence and satisfaction in their vocation has decreased significantly in the past few years, and two in five (41%) say they’ve considered quitting ministry in the last 12 months.”

But an expert on congregational health said these and other well-known trends in the American church aren’t limited to ministers and are nothing to lose hope about.

“The clergy are the canary in the coal mine here.”

“There are a lot of men and women who are hurting in ministry, and I don’t want to minimize the fact that a lot of minsters need a good counselor or a therapist,” said Bill Wilson, founder of the Center for Healthy Churches. “But this is a North American church issue. The same statistics would probably be true not just of clergy, but of lay leaders, and I think congregations are discouraged. The clergy are the canary in the coal mine here.”

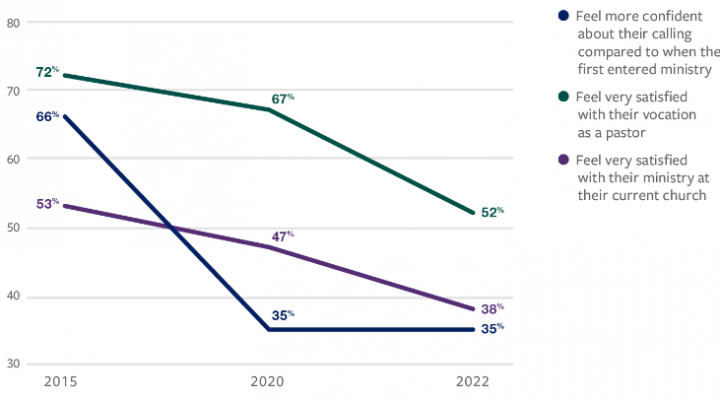

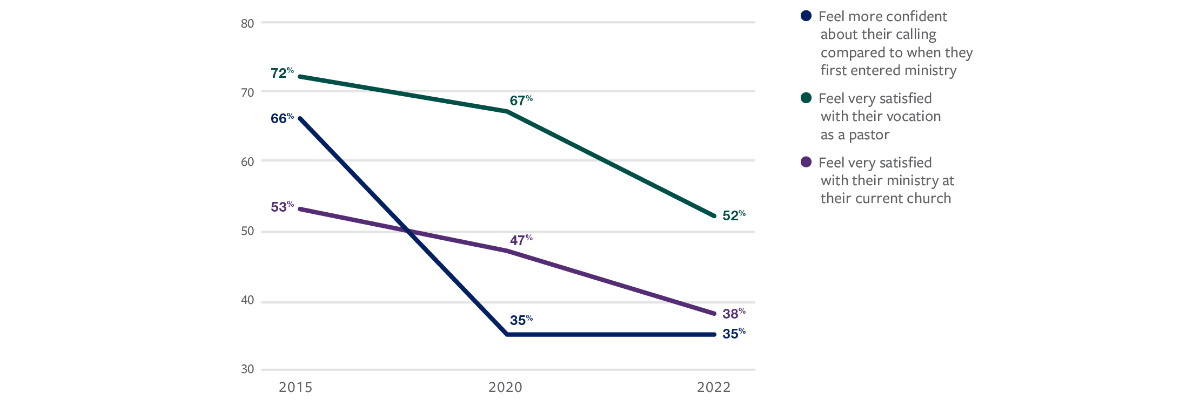

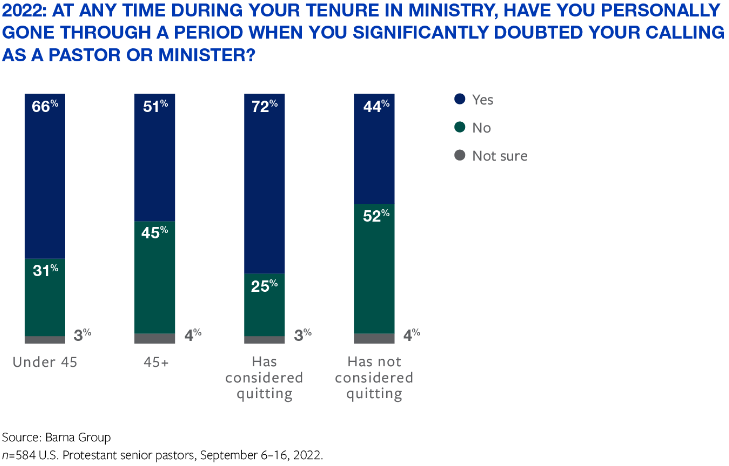

But they are also struggling considerably, according to the Barna study that reported sharply increased feelings of loneliness among pastors. In 2022, 52% of pastors reported being “very satisfied” with their jobs, down from 67% in 2020 and 72% in 2015.

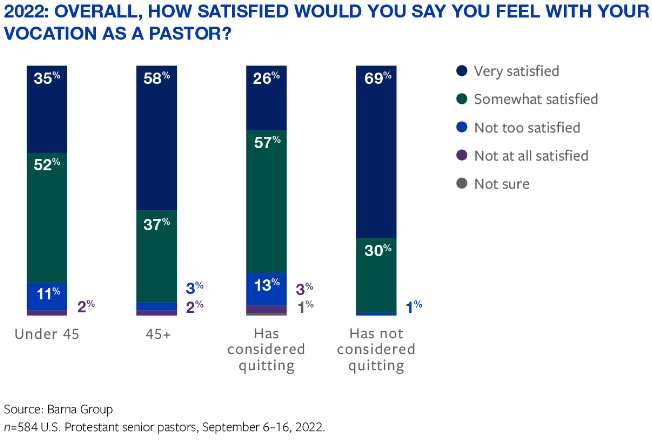

“Overall, the percentage of pastors who say they have gone through a period when they significantly doubted their calling for ministry has more than doubled since 2015 (from 24% to 55% in 2022),” according to the study. “Pastors aren’t just broadly less happy with their work than they used to be, they may also be less sure of where they’re supposed to be.”

And the trend is “especially notable among younger pastors — just 35% of pastors under 45 say they are ‘very satisfied.’ This troubling decline in vocational satisfaction may cause significant problems for churches in the future,” Barna said.

Wilson said those problems, although real, are not the entire story. “We are coming up on a season — the biblical metaphor would be pruning — that is challenging, but there is hope that what emerges beyond this season of turmoil is going to be somehow better in some respects.”

In part, past experience suggests there will be light at the end of the tunnel for ministers and congregations, he added. “The church has always been at its best when the challenges were most severe. From the beginning, it’s been our MO that we rise to the occasion. So, there is a sense in which these are tough days, but we are going to be fine, we are going to survive this. That doesn’t make the person in ministry feel any better, but I don’t want to leave people just frightened.”

But it will take dedication and creativity for churches to respond to the cultural trends that are keeping sanctuaries and Sunday school classrooms underutilized, he said.

“Congregations and minsters have to reframe these challenges. We have been waiting for an invitation to be innovative, even entrepreneurial. Here’s our chance because the old ways of doing ministry are not producing results.”

The “paint-by-numbers” approach to ministry must be traded for imagination and the willingness to experiment with new configurations of being church, he explained. “A lot of people are saying, ‘We just want it to be the way it used to be. We want our robed choirs back and leave us alone.’ But that isn’t going to happen.”

Bill Wilson

While Wilson said he has no bullet list for what new options can or should be, one place to start is identifying ways to engage with young people.

“I have seen churches putting together dream teams and pushing themselves out of their comfort zones to listen to the world around them,” he said. “The data out there show the No. 1 social issue is loneliness, especially around Generation Z.”

Churches that are open to change are well positioned to provide access to authentic community to young people and others who are lonely “in this unsettled season,” Wilson said.

“For churches with way too much building and way too few people, being entrepreneurial could mean repurposing congregational facilities for the good of the community. Is it a bad thing or a good thing that we have unused space? Well, it’s both, but instead of lamenting that we don’t have five children’s rooms filled with children anymore, maybe consider that it means we have four rooms available for other things.”

Related articles:

If a story is meant to evolve, then so are we | Opinion by Kaitlin Curtice

The present crisis for church staff | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Churches must learn to adapt to ‘permanent transition,’ Leonard stresses