Like people around the world, Frances Fuller was deeply grieved by the Aug. 4 explosion that killed nearly 200 people and displaced another 300,000 in Beirut, Lebanon.

But for Fuller, 91, watching the indescribable carnage was personal. She saw in the faces on her TV screen people she knew and loved. And she was transported back to the 30 years she and her late husband, Wayne, spent as Baptist missionaries in Lebanon. In that span ending in the mid-1990s, the couple was exposed to innumerable instances of military and terrorist violence — sometimes as targets themselves.

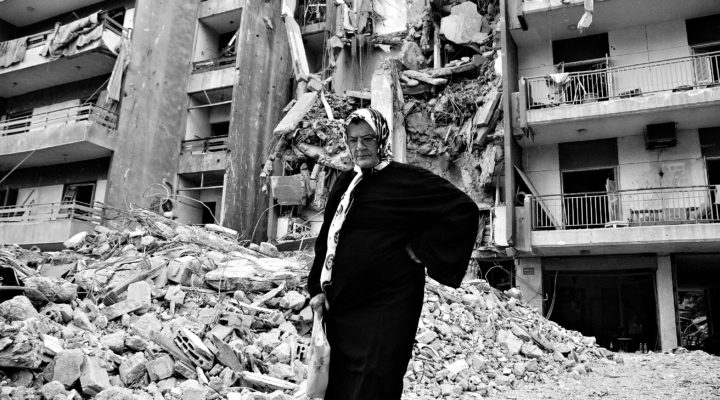

“For a whole day, I cried while watching the same newsreels over and over, the pictures of Beirut in a mushroom cloud, in flames, in flying shards, in broken walls and tumbling cars, her stunned people covered with blood,” Fuller shared in a blog post.

Frances and Wayne Fuller in Lebanon, 1979. (All photos courtesy of Frances Fuller)

Her 2017 book, In Borrowed Houses: A Memoir of Love and Faith Amidst War in Lebanon, displays her admiration and spiritual connection to the people of Lebanon. So do her social media accounts. “Seventy-five percent of my Facebook friends are Lebanese,” she said.

Fuller said she was inspired during her time in that country, and in the years since, by the devotion her Christian friends, Baptist or otherwise, showed to family and faith during even the most violent of times.

“We were there when the Israelis invaded (1982). We saw history happening,” Fuller said. “We experienced shelling. I personally got shot at by a sniper more than once while I was out doing my work.”

That work was to direct the Near East publishing ministries for the Foreign Mission Board of the Southern Baptist Convention. She also served as the board’s press representative in the region.

The California resident continues to write books and blog in keeping with the calling she sensed to serve others through the written word. Her journey includes growing up Baptist in Arkansas, majoring in journalism in college and following the Spirit’s push to Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary in the early 1950s.

Fuller is aware that she stood out as a woman in the male-dominated SBC.

Frances Fuller as a Baptist missionary in Lebanon.

“What I really wanted at Golden Gate was to deepen my understanding of the Scriptures, but at that time they wouldn’t let me enroll in the ministry program that the men all took,” she recalled. “All the women had to enroll in religious education.”

So, she enrolled. But she also was tapped to work in the public relations office at what was then a brand-new institution in California. “It was my responsibility to get it on the map,” she said.

The experience helped clarify how her writing and editing talents could be used for ministry. “I had grown spiritually to the place where I felt that everything was stewardship.”

She and Wayne met at Golden Gate. “Together we committed ourselves to missions, and when the Foreign Missions Board asked us where we wanted to go, we told them the Arabic world.”

Delighted at the choice, the board initially assigned the couple to Jordan, preceded by a period learning Arabic in Lebanon. Then they settled in Amman, the Jordanian capital.

“We had a ministry to students in our home and Sunday worship in our home and during this time I was writing for the (FMB’s) publishing house and was their press rep.”

Military conflict intervened, however. “The civil war in Jordan got so bad” that they returned to Lebanon “for safety’s sake.”

The mission board’s Near East publishing activities were based in Lebanon, and Fuller was hired on and later became director after her predecessor, Virginia Cobb, died of cancer in 1970.

Fuller, who ran the program for 24 years, said it was unusual for women to have such high-profile roles within the mission board’s operations. But this was a case where education, experience and calling superseded convention.

“I was the only person in whole Near East Baptist Mission — Lebanon, Jordan and Egypt — who had any background that seemed to equip them to do that job,” she said. “We came into this place where there was such a dearth of Christian literature, and we did historic things. The books we published have become the basic Christian library in the Arabic language.”

Frances Fuller and her publications staff in Lebanon in 1985.

Those works include an atlas of the Bible and children’s books that even Muslims sometimes purchased. “You can write a lovely little book about God that appeals to the Muslims as much as it does to Christians,” she explained.

The concordance had an especially significant impact, she added. “The Bible had been in the Arabic language for a thousand years, but Arab Christians didn’t have a way to study it. So, a concordance was essential.”

Arab Christians were hired as editors and writers to ensure books, pamphlets and other materials were culturally relevant. It proved to be a vital practice in the publishing of children’s Sunday school curricula.

“In the Arab world, if there were 25 in church there were 75 in Sunday school,” Fuller explained. “The materials they had before, which had been translated, didn’t fit into their culture.”

But rising military and guerrilla activity were taking their toll in Lebanon, and the kidnapping of Westerners was generating international headlines by the early 1980s. A lot of foreign nationals fled, but not the Fullers. “There were times when you knew this street or that street wasn’t safe. We were careful, but we were stubborn too,” she said.

The couple eventually left for Cypress in 1987 after the U.S. ordered its citizens out of the country. “It was the worst thing that ever happened to me,” she said.

Frances Fuller with a Lebanese friend.

But Fuller found a loophole enabling her to enter and leave Lebanon each day by ferry. She was soon back at her desk overseeing the publishing ministry. “I got the OK to go in and out as long as I promised not to cause an international situation.”

Even then she learned an important lesson about Christian work in Lebanon: “In the whole of the Middle East there is very little emphasis on denomination. But during these wars our church grew even when others were fleeing. People just needed something spiritual, something that couldn’t be blown up by a bomb.”