Evangelicals have made it clear: Don’t call us racists. We are not racists.

Rather than debate the issue, I volunteer to take the word “racist” off the debate table. Instead of calling evangelicals “racists,” I will use the word “heedless.” I believe this is the exact word for evangelical ideology on issues that relate to race.

Norman Fischer in his translation of Psalm 1 uses the word “heedless” instead of the word “wicked”:

Happy is the one who walks otherwise

Than in the manner of the heedless.

The heedless … are like chaff scattered by the wind

Endlessly driven, they cannot occupy their place

And so can never be seen or embraced

And they can never be joined.

The way of heedlessness is oblivion.

Instead of shaming people with words like “wicked,” “evil” or “racist,” the chosen word is “heedless.” The “heedless” are still capable of transformation, and I set them off from those who dehumanize and degrade others as part of some political masquerade. The wise woman of Proverbs set these workers of iniquity apart as “sinners,” “scorners,” “mockers” and persons “whose speech is twisted.”

While the rest of the diverse population of the United States grounds common life in ontological connectedness, evangelicals resist the uncomfortable “otherness.” A majority of Americans shout, “We are in this together, for each of us is a part of a body.”

Many evangelicals are “heedless” of this relentless march toward connectedness with all other humans and the environment. Thus, we are in a rhetorical war of charges and countercharges.

“Many evangelicals are ‘heedless’ of this relentless march toward connectedness with all other humans and the environment. Thus, we are in a rhetorical war of charges and countercharges.”

Both sides with similar dilemmas

Liberals shame conservatives; conservatives lash out with wounded pride and assert dignity. Liberals cry, “Racist!” Conservatives deflect with, “We are not racists.”

Charles Taylor, in his monumental book A Secular Age, suggests that “the general shape of the struggle seems to be this, that both sides are at grips with similar dilemmas, each within a different understanding of the human predicament. In the one-sided heat of the debate, this generally disappears from view, and huger rocks are thrown by either side than are safe for dwellers in glass houses.”

How painful it must be for persons of color — persons who actually embody the struggles and agonies of racism — to be mostly left on the sideline watching white people argue over who is and who is not racist. Perhaps this is the very definition of heedlessness — debates that leave out the subjects of the debate and reify them as objects.

When we rail at evangelicals for being “racists” or “evil” or “wicked,” we defy our own ontological commitments to sympathy, understanding and love. I believe most evangelicals are mistaken in how they approach issues of race — they are mistaken at the ontological level. They are heedless.

“How painful it must be for persons of color — persons who actually embody the struggles and agonies of racism — to be mostly left on the sideline watching white people argue over who is and who is not racist.”

In protest after protest, evangelicals pit themselves against others in an attempt to impose the evangelical will on others. Whether they are attacking the standards of science in public schools because of evolution or the social studies standards because of Critical Race Theory, their interactions suggest living heedlessly.

We are a heedless people

I looked up the definition of heedless: “Showing a reckless lack of care or attention, paying no heed to, inattentive, and oblivious to.”

Examples of heedlessness abound in our nation. A guy drives 110 miles per hour on I-890, cutting off other drivers, endangering lives, because he’s late for dinner. Heedless. The third guy in the turn lane runs the red light because he can. Heedless. A woman takes a private jet to D.C. on Jan. 6 and wanders into the Capitol with the crowd. Heedless. A protester throws a rock through a store window. Heedless. A mother in Virginia threatens the local school board on mask mandates: “I will bring every gun loaded.” Heedless. Airline passengers attack flight attendants over mask mandates. Heedless.

Multiply the ways that we are a physically heedless people.

The heedless, like the metal ball in an old-fashioned pinball machine, ricochet from cause to cause in fear, outrage and a sense of “I’m not going to take it anymore.” In contrast, the wise woman of Proverbs observes, “By insolence the heedless make strife” (Proverbs 13:10).

The heedless are thrown about by every wind of emotion, rumor and conspiracy, the mistrust of government, the whims and fads of the moment. I am convinced that much of our violence is related to becoming a heedless people.

“The heedless are inattentive to realities, facts, even truth itself.”

The heedless are inattentive to realities, facts, even truth itself. The battle here is against a certain kind of ignorance of the interconnectedness of all beings. People act heedlessly when they pit themselves, unnecessarily, against others. This is not a denial of people being evil, but a realization that heedlessness can be corrected.

Heedlessness and sloth

The ancient church had a word that suggests heedlessness: acedia or sloth. One of the seven cardinal sins, acedia means “not caring.” Chaucer says that sloth “makes (us) brooding and fretful.” It “severs a man from all love.” And “sloth does all things with vexation, fretfulness, slackness, excusing, idleness and reluctance.”

“Sloth is the sorrow of goodness and the joy of harm,” Augustine put it.

Perhaps the most telling explanation of sloth in Canterbury Tales are these words: “Sloth will not abide hardship nor Penance.” Chaucer shows that sloth, refusing repentance or change, becomes sluggish, and then, reacting against being shamed, becomes angry and “is soon inclined to hate and to envy.”

Evangelicals need to ask why they are so angry. Why is there all this white rage in the country?

“Evangelicals need to ask why they are so angry. Why is there all this white rage in the country?”

American historian David Blight muses: “The lies have now crept into a Trumpian Lost Cause ideology, building its monuments in ludicrous stories that millions believe, and codifying them in laws to make the next elections easier to pilfer. If you repeat the terms ‘voter fraud’ and ‘election integrity’ enough times on the right networks, you have a movement. And ‘replacement theory’ works well alongside a thousand repetitions of Critical Race Theory, both disembodied of definition or meaning, but both scary. Liberals sometimes invite scorn with their devotion to diversity training and insistence on fighting over words rather than genuine inequality.”

Heedlessness and race

Is heedlessness the root of our problems with race? Ignoring injustice piled up at our door for more than 400 years. Inattentive to the needs of African Americans. Intoxicated by our own imperialism and consumerism and greed. Refusing to even entertain the idea that repentance may be the necessary step forward for us all. Rage may be more emotionally satisfying to people who have been shamed by liberal pedagogy.

Brian Ott and Greg Dickinson, in The Twitter Presidency, locate white rage in “the fear and anxiety surrounding the social decentering of white privilege and hegemonic masculinity.”

Perhaps our heedlessness keeps us from actually understanding what constitutes racism. When a white evangelical says he is not racist, he is sincere. Most likely, he is not prejudiced in an individual sense, and he is accepting of all others. This doesn’t mean he is an antiracist. As long as the simple definition of racism remains individual or personal prejudice, we are not even approaching our culture’s systemic and institutionalized racism.

“Perhaps our heedlessness keeps us from actually understanding what constitutes racism.”

Ibram X. Kendi in How to Be an Antiracist defines racism as “a marriage of racist policies and racist ideas that produces and normalizes racial inequities.” He adds that “racial inequity is when two or more racial groups are not standing on approximately equal footing” and a racist policy amounts to “any measure that produces or sustains racial inequity between racial groups.”

What Kendi offers us is an elegant starting point for not being racist: Be antiracist.

Insisting, “I am not a racist,” is not enough. Protesting Critical Race Theory doesn’t make the case for anyone being antiracist. Action that helps create a system and institutions that are antiracist is the only legitimate means of addressing our problem with race.

Saying, “I’m not a racist” is not evidence for anything other than a suggestion of denial or a cover-up. The thoughtful and attentive will discern the racist nature of our nation from its founding to the present moment. Instead of drawing a line in the sand and making war over ill-prepared tropes like “political correctness,” “wokeness,” or Critical Race Theory, the way of the antiracists is more than a tropological war; it is a politics of interaction, engagement and relationship building.

By undertaking the spiritual discipline of becoming an antiracist, we will be more compassionate, loving, mindful, grateful citizens. Only then will we transform our current racist antagonisms into agonism — a contest of debate, discussion, discernment and transformation.

We’ve got to talk about it

My mother had many rules, many of them confusing and indecipherable, but one rule topped all the others: “If you don’t talk about it, it didn’t happen.” Heedlessness is here made into a commandment, a carved-from-stone commandment with epistemological status. Evangelicals seem determined not to have the conversations about race that are necessary for us to have healing, closure and an ascending antiracism.

Who do you know who really wants to produce an ontological connection between America’s left and right wings?

Blight asks: “Who do you know who really wants to compromise with their ideas? Who on the left will volunteer to be part of a delegation to go discuss the fate of democracy with Mitch McConnell, Kevin McCarthy or the foghorns of Fox News? Who on the right will come to a symposium with 10 of the finest writers on democracy, its history and its philosophy, and help create a blueprint for American renewal?”

Learning from the African American prophetic tradition

We never will make serious progress on race until we make the connection between African Americans and democracy. Cornell West shakes the rafters of our minds with these searing words: “The Black prophetic tradition has been the leaven in the American democratic loaf. What has kept American democracy from going fascist or authoritarian or autocratic has been the legacy of Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Martin King, Fannie Lou Hamer. This is not because Black people have a monopoly on truth, goodness or beauty. It is because the Black Freedom movement puts pressure on the American empire in the name of integrity, decency, honesty and virtue.”

Instead of accusations of racism and the denials of racism, there needs to be an appropriation of the African American prophetic tradition as one way to save us from heedlessness in the facing of our race problem.

Again, it is West sounding the alarm: “It may very well be that Black people will never be free in America. But I believe, and the Black prophetic tradition believes, that we proceed because Black people are worthy of being free, just as poor people of all colors are worthy of being free, even if they never will be free. That is the existential leap of faith.”

I have confidence that such Americans willing to take the leap of faith still exist. In the streets of America, I still see faithful citizens leaping and dancing like King David as racism folds its tent and becomes extinct. By God’s help, Americans can learn to “leap over all walls” constructed to keep others apart.

“I refuse to employ the rhetoric of blame for the majority of our citizens.”

I refuse to employ the rhetoric of blame for the majority of our citizens. There’s still a sense of “fellow Americans” out there that has been silent too long. Away from the digital “uncivil war” of tweets, advertisers, political consultants, hate-producers, there is an American voice.

Inspiration from three prophets

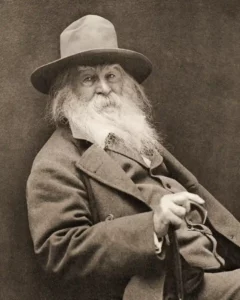

The bard of democracy, Walt Whitman, can come once again singing his tune of making space for everyone. Remember Whitman: No games of normal and abnormal. All welcome — runaway slaves, prostitutes, farmers, mothers, children, dock workers, common workers, the deformed and sick, the poor and destitute, all have their place at the table.

Walt Whitman

Perhaps the most important contribution of Whitman was his vision of a universal community without division, gated communities and separate spheres. Whitman posits an “us” without a “them.” This is the ideal good, the goal of antiracism. This is, of course, a religious undertaking. Here is a soteriology that includes everyone, a community without barriers, fences, railroad tracks (as in “the wrong side of the tracks”), ghettos, “hoods,” or walls.

Here’s a bit of Whitman’s song: “This is the meal pleasantly set …, this is the meat and drink for natural hunger, it is for the wicked just the same as the righteous. … I make appointments with all, I will not have a single person slighted or left away, the keptwoman and sponger and thief are hereby invited … the heavy lipped slave is invited … the venerealee is invited, there shall be no difference between them and the rest.”

Ah, the glory of true democracy — the amazing miracle of synthesis bringing the high with the low, rich with poor, men with women, white with Black, North with South, East with West.

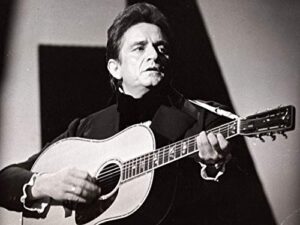

Johnny Cash

There are, of course, other voices. Perhaps there’s surprise that one of those voices was Johnny Cash.

There’s a place I know where the train goes slow,

Where the sinner can be washed in the blood of the Lamb.

There’s a river by the trestle down by sinner’s grove,

Down where the willow and the dogwood grow.

And I know that your name can be on that list.

There’s no eye for an eye, there’s no tooth for a tooth.

I saw Judas Iscariot carrying John Wilkes Booth,

He was down there by the train.

And all the shamefuls and all of the whores

And even the soldier who pierced the side of the Lord

Is down there by the train.

Meet me down there by the train.

There’s one more voice I offer, not a democratic one, but the moral imperative of a Hebrew prophet who went by the name Isaiah: “On this mountain, the Lord of hosts will make for all peoples a feast of rich food, a feast of well-matured wines, of rich food filled with marrow, of well-matured wines strained clear. And he will destroy on this mountain the shroud that is cast over all nations; he will swallow up death for ever. Then the Lord God will wipe away the tears from all faces, and the disgrace of his people he will take away from all the earth” (Isaiah 28:24-26).

Whitman the poet, Cash the country musician, and Isaiah the prophet — a veritable trinity of democratic voices singing the glory of attentiveness, thoughtfulness, discernment and the danger of heedlessness. With Whitman I now cry, “I speak the pass-word primeval, I give the sign of democracy, By God! I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms.”

Welcome to the table — the sacrament of “us” without a “them.”

Rodney W. Kennedy currently serves as interim pastor of Emmanuel Freiden Federated Church in Schenectady, N.Y., and as preaching instructor Palmer Theological Seminary. He is the author of nine books, including the newly released The Immaculate Mistake, about how evangelical Christians gave birth to Donald Trump.

Related articles:

Everything you need to know about the rise in efforts to ban books from libraries | Analysis by Mark Wingfield

Who’s behind the nationwide attacks on local school boards over Critical Race Theory?