It is better to give than to receive, in basketball and in life.

Let’s start with basketball. When it’s played the right way, there’s nothing more beautiful in sports, whether it’s a March Madness matchup on national TV or a pickup game on some anonymous blacktop. And the most beautiful play in basketball is the pass, especially the assist — the pass that leads directly to a basket.

Laker legend Earvin “Magic” Johnson, my all-time favorite player, was the Picasso of the pass, the artist of the assist. He was a superstar, to be sure, but he got a lot more satisfaction out of making a great pass to a teammate streaking to the basket than making a basket himself.

Current NBA Most Valuable Player Nikola Jokic of the Denver Nuggets models the same team-first mentality. His all-around game is amazing, but his passes sometimes defy belief. As the crowd goes wild, he shrugs and jogs back down the court to play defense, acting like it’s all in a day’s work.

See, basketball is a team game. Dunks and halfcourt three-pointers are great, but they don’t win championships. Selfless play does.

Bill Walton, the redheaded, 6-foot-11-inch center, philosopher and joyfully weird commentator, who died of cancer May 27 at 71, believed in selfless play with all his heart.

“In basketball, you can be the greatest individual player in the world and still lose every game, because a team will always beat an individual.”

“In basketball, you can be the greatest individual player in the world and still lose every game, because a team will always beat an individual,” Walton said. “Success at the highest level comes down to one question: Can you decide that your happiness can come from someone else’s success? Never forget: Happiness ends when selfishness begins.”

No one can dispute Walton’s success on the court: His UCLA teams were undefeated national champs twice from 1972 to 1974. They went 86-4 when he was starting center. He was the NCAA basketball Player of the Year three times.

“He was, without argument, one of the two greatest players in college basketball history — along with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, known as Lew Alcindor during his college days (also at UCLA) — and remains so to this day,” wrote Jay Bilas, a close friend of Walton and fellow ESPN sportscaster. “Walton was the most complete center in the game: scoring, rebounding, blocking shots, passing, outlet passing and running the floor.”

In the NBA, Walton led the Portland Trail Blazers to the league title in 1977 and was named the Finals MVP. The next year he was league MVP. Then came years of chronic, debilitating injuries. But he returned to late-career glory as a key player and NBA Sixth Man of the Year with the 1986 league-champion Boston Celtics. After retiring from basketball in 1990, he was elected to the Naismith Hall of Fame, and in 1996, to the NBA’s inaugural 50 Greatest Players list.

For all his glitzy numbers, Walton reportedly checked one personal stat after every game: assists. His happiness came from his teammates’ success.

Generosity, zest and zaniness

He took the same team-first approach to life — with a mixture of generosity, zest and sheer zaniness we’ll probably never see again. Not in this solar system, at least. Maybe in some other, groovier galaxy, where Walton and Grateful Dead founder-guitarist Jerry Garcia might be tuning up even now for a thousand-year jam session.

“He took the same team-first approach to life — with a mixture of generosity, zest and sheer zaniness we’ll probably never see again.”

Walton was the ultimate Deadhead, as the venerable band’s fans are known. Many of them followed the Dead around the country — and the world — for years on end to participate in the marathon, mind-altering experience of their live shows. Walton attended more than 850 Dead concerts, including a famous gig at the pyramids in Egypt where he joined the band onstage to play drums. Whenever he was in the audience, you could easily spot him in his trademark tie-dyed T-shirt, red head bobbing up and down above the crowd. He was 6 foot 11, after all.

But the Dead were just one of Walton’s many passions. He loved nature. He loved riding his bicycle. He loved fighting for racial and social justice with an unapologetically leftwing, anti-establishment perspective. He loved ideas. He loved the Pac-12 college sports conference and especially UCLA, his beloved alma mater. He loved Coach John Wooden, the legendary, bespectacled “Wizard of Westwood” who led UCLA to 10 NCAA basketball championships (including the two with Walton at center).

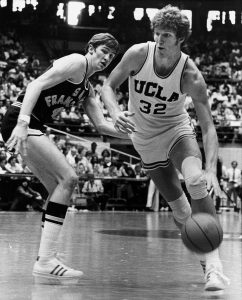

UCLA’s Bill Walton dribbles around San Francisco’s Eric Fernston in the NCAA west regional playoff in Tucson March 1974. (AP Photo)

Despite their radically different personalities, Wooden was Walton’s dearest friend and closest mentor (Walton called Wooden twice a week until Wooden’s death, at age 99, in 2010). They were the odd couple of American sports: Wooden, the conservative traditionalist and devout Christian. Walton, the longhaired, bandana-wearing radical.

Walton initially refused Wooden’s order to get a haircut before playing for UCLA.

“We’ll miss you,” Wooden responded.

Walton reluctantly rode his bike across campus to a barbershop. But Wooden had to make compromises, too. He bailed Walton out of jail after the young player was arrested for protesting the war in Vietnam.

Walton may not have embraced Wooden’s deep Christian faith, but he zealously adopted his mentor’s commitment to character and values.

Thousands of friends

Most of all, Walton loved people. Thousands of people. He actually had that many friends in later life. Amazing, when you consider he was agonizingly shy well into adulthood. A childhood speech impediment silenced him until he overcame it in his late 20s with the help of famed New York sports announcer Marty Glickman.

“I’m a stutterer,” Walton recalled. “I never spoke to anybody. I lived most of my life by myself. As soon as I got on the court I was fine. But in life, being so self-conscious, red hair, big nose, freckles and goofy, nerdy looking face and can’t talk at all. I was incredibly shy and never said a word. Then, when I was 28, I learned how to speak. It’s become my greatest accomplishment of my life and everybody else’s biggest nightmare.”

Walton more than made up for lost time as a communicator after retiring from basketball. He became a popular — and hilariously off-the-wall — color commentator during 30 years of college and NBA hoops broadcasts. You never knew what he was going to say, or whether it would relate to the game at hand. But it was guaranteed to be entertaining.

One of my favorites among thousands of Walton play-by-play observations: “Come on, that was no foul! It may be a violation of all the basic rules of human decency, but it’s not a foul.”

Another time, he declared then-Utah Jazz point guard John Stockton to be “one of the true marvels, not just of basketball, or in America, but in the history of Western civilization!”

His broadcast partner that night, Tom Hammond, responded, “Wow, that’s a pretty strong statement. I guess I don’t have a good handle on world history.”

Walton: “Well, Tom, that’s because you didn’t go to UCLA.”

For all his fame, talent and latter-day comedic craziness, Walton had one guiding characteristic, according to Bilas, his friend and fellow broadcaster: “When all would be thrilled to hear Bill talk about himself and his rich life in the game, he would never fail to ask questions about you. He was genuinely interested in you. …

“Walton was about enjoying every minute of his existence and making your existence around him meaningful and unforgettable. He was a free spirit, with endearing eccentricity. But deep down, he was about finding joy in others.”

Which brings me back to my first sentence: It is better to give than to receive, in basketball and in life.

Erich Bridges, a Baptist journalist for more than 40 years, has covered international stories and trends in many countries. He lives in Richmond, Va.