The election of President Donald Trump reveals a side of America long known to people in marginalized communities, says ethics professor, author and activist Miguel De La Torre in a new book calling for faithful resistance to systems that perpetuate social and economic injustice.

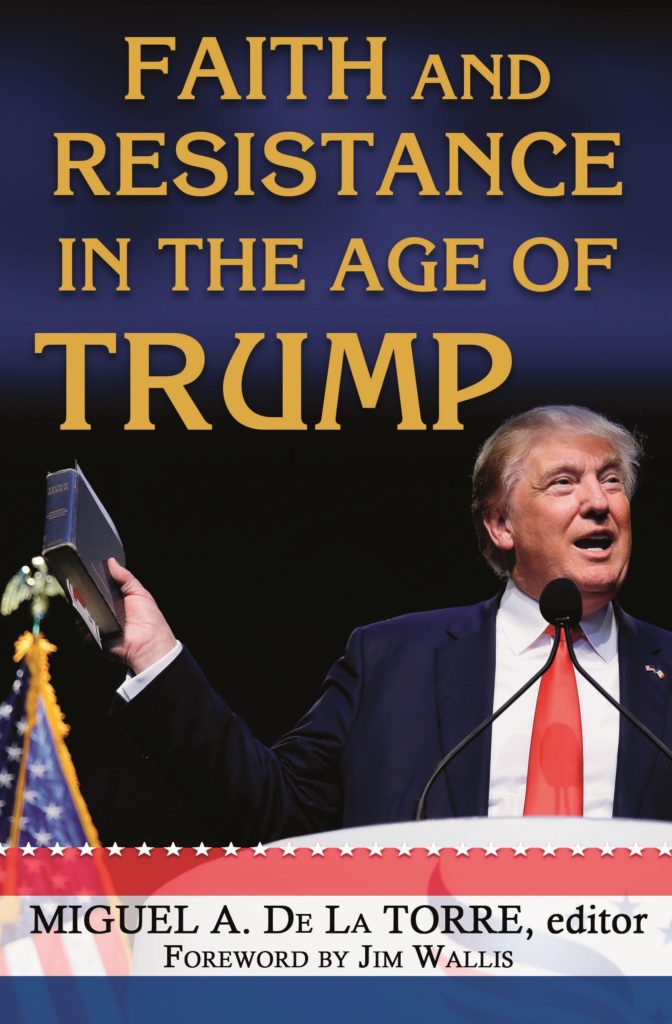

“For marginalized communities in the United States, especially racial and ethnic communities, Donald J. Trump is the true face of America,” De La Torre, professor of social ethics and Latinx studies at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver, says in the final chapter of Faith and Resistance in the Age of Trump, a collection of essays due out Sept. 14.

“It is the face we have confronted throughout most of our interactions with societal authorities, though it remained masked to those in the dominant culture who embraced the illusion of a post-racial society,” he says. “On election night, that mask was ripped aside, revealing that face to society at large, and leaving many of us terrified.”

De La Torre, a Baptist News Global columnist, says in the introduction that he and the other 24 authors of the book “are not seeking simply to contribute a harangue about why we think Trump is the antithesis of what we claim are the core beliefs of any faith rooted in justice.”

The book, submitted to the publisher just three weeks after Trump took office, rather wrestles with the “why” of Trump and what it means for progressive faith communities during the next four to eight years.

De La Torre, born in Cuba eight months before the Castro-led revolution overthrew U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959, says in his chapter that he found rare agreement with then-candidate Trump in the months leading up to November when Trump kept insisting the electoral system is “rigged.”

De La Torre says the popular “myth” about why the president is elected by the Electoral College instead of popular vote is that 1787 Constitutional Convention wanted to protect smaller states from large states amassing too much power at their expense. He says the real issue was that slave states had larger non-voting populations (i.e., humans who were enslaved), so the Electoral College was a compromise to add clout to Southern states in the presidential election.

He says institutions like the Electoral College, along with tactics including gerrymandering and voter suppression, continue to benefit those holding on to power and limit the ability of those on the margins to bring about change.

De La Torre says in a chapter completed months before events in Charlottesville, Va., that it is impossible to “ignore those on the alt-right extreme” who helped bring Trump to power, but the “moveable middle” who voted for him, many after previously voting for Obama, is harder to explain.

“Many of those who voted for Trump assure us that misogynist, racist, homophobic, xenophobic and Islamophobic motives were not the reason they cast their votes,” De La Torre writes. “But underneath their reasons it is impossible to ignore the element of white privilege among this moveable middle. If it was not because of his racist, misogynistic, xenophobic, Islamophobic positions that they supported it, they nevertheless found it possible to support him despite these positions, because he did not threaten their existence.”

Similarly, while it’s easy to identify physical violence in overt acts such as hate crimes, De La Torre says “the more insidious violence is normalized in social structures designed to exploit one group of people (usually along race, ethnic, and gender lines) so the minority can live a life of power and privilege.”

Similarly, while it’s easy to identify physical violence in overt acts such as hate crimes, De La Torre says “the more insidious violence is normalized in social structures designed to exploit one group of people (usually along race, ethnic, and gender lines) so the minority can live a life of power and privilege.”

While not dismissing physical violence, he and the other authors talk primarily about what theologians call “institutionalized violence.”

“When a police officer pulls over an unarmed person of color and ends up shooting him or her, that is a vivid example of physical violence,” De La Torre writes. “Redefining violence to encompass its institutional manifestations shifts the emphasis from an individual act that can be dismissed as some unfortunate outlier (a bad apple) toward collective and social phenomena with which society as a whole — its political administration, governmental agencies, corporations, financial institutions and a militarized police apparatus — is complicit.”

De La Torre says he and the other authors aren’t interested in making America “great again” — if what that means is returning to a time when people like Native Americans, blacks, women, Latinx and others weren’t wanted here in the first place.

“Our call is to create a new America that moves beyond its oppressive racist, imperialist and misogynist past toward a new possibility, a possibility that takes seriously the rhetoric of ‘liberty and justice for all.’ This is a vision for a new America that has yet to exist, an America that cannot be achieved under a Trump administration,” he writes.

De La Torre admits the Trump years aren’t going to be easy for people like him, and some may be tempted to give up, but he believes there is a role in the current political climate for active resistance to powers that be.

As he has in some of his previous books, De La Torre calls for an ethics of “joder” — the Spanish equivalent to the four-letter term that in English slang literally refers to sexual intercourse but in non-vulgar usage can mean to annoy, bother, irritate or put someone in a difficult situation.

“An ethics para joder fosters an effective response to the consequences of a Trump regime,” he explains. “To joder is to resist. A joderon is one who strategically becomes a royal pain in the rear end, purposely causing trouble, constantly disrupting the established norm, shouting from the mountaintops what is supposed to be kept silent, audaciously refusing to stay in one’s assigned place. To joder is to create instability, upsetting the prevailing social order designed to maintain the law and order of the privileged.”

“Think of Jesus cleansing the Temple, the liberative praxis of literally overturning the established tables of order and oppression (Matthew 21:12-13),” he continues. “To joder is to overturn established tables. Political and social change requires going beyond the rules created by the dominant culture, moving beyond what is expected, pushing beyond universalized experiences.”

Other contributors to Faith and Resistance in the Age of Trump include Jim Wallis of Sojourners, Baptist ethicist David Gushee, former Chicago Theological Seminary President Susan Brooks Thistlethwaite and Sister Simone Campbell, founder of Nuns on the Bus. It is published by Orbis Books, the publishing arm of the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers, a Catholic order dedicated to missionary work among the poor on the fringes of society.