By Marv Knox

When Ebola arrived in America in the autumn of 2014, fear spread faster and further than the deadly virus. But hope sustained the family at the epicenter of the hysteria.

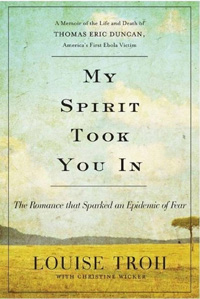

My Spirit Took You In: The Romance that Sparked an Epidemic of Fear tells the poignant story of Thomas Eric Duncan, America’s first Ebola victim, as well as his fiancé, Louise Troh, and her family.

It’s a harrowing story of love and loss. But it features grace and redemption. Thanks to a courageous and compassionate county judge, a wise and tenacious pastor, and a loving and selfless congregation, Troh and her family did not suffer alone.

It’s a harrowing story of love and loss. But it features grace and redemption. Thanks to a courageous and compassionate county judge, a wise and tenacious pastor, and a loving and selfless congregation, Troh and her family did not suffer alone.

Duncan and Troh fled civil war that ravaged Liberia in 1994. They found each other, and love, in the unlikeliest of places — the Danané refugee camp in neighboring Ivory Coast.

“Liberians ran to the Ivory Coast because of the terrible things that soldiers were doing to the people of my country,” Troh writes. She recounts a litany of woes — 700,000 of 2 million Liberians displaced, 5 percent of the population killed, refugees still scattered abroad.

When Duncan saw Troh walking along a dusty road, he called out to her. Their lives changed forever in that moment. “It was like God picked us for each other,” she says, comparing finding the love of her life in a refugee camp to discovering “a diamond in the dirt.”

“Our spirits knew each other from that first day,” she reports. Love blossomed amidst the poverty and uncertainty. The didn’t marry, at least by Western standards. But they had a son, Karsiah, and Duncan considered Troh his wife forever.

Although their love held strong, global politics and the economics of extreme poverty tore them apart—at least physically.

In 1998, Troh received a single visa to immigrate to the United States. The U.S. Refugee Admissions Program granted her and 16 brothers and sisters political asylum. Their father immigrated years before and worked tirelessly to bring his children to a new land of peace and unimagined opportunity.

Troh points out the paradox of loving Karsiah, then only 2 years old, and his older step-siblings, and leaving them behind in Africa. “Only a really terrible mother would stay in Danané because she was unwilling to make the sacrifice of leaving her children,” she explains. “I can never forgive myself for leaving my children. But to stay in the Ivory Coast would have been more unforgivable.”

Troh points out the paradox of loving Karsiah, then only 2 years old, and his older step-siblings, and leaving them behind in Africa. “Only a really terrible mother would stay in Danané because she was unwilling to make the sacrifice of leaving her children,” she explains. “I can never forgive myself for leaving my children. But to stay in the Ivory Coast would have been more unforgivable.”

So, Troh left for America, alone. Later, she succeeded in obtaining visas for Karsiah and several of her children. She eventually landed in Dallas. She found hard-but-helpful work in a nursing home. And she became the matriarch for a clan of children, grandchildren and an extended family of various relations. Her apartment in the Vickery Meadows section of North Dallas became their center of gravity. She filled their bodies with traditional African dishes she cooked up in huge pots and pans. She filled their hearts with love and African song.

Troh and Duncan kept in touch. He stoked her hope with plans to follow her to America, to work hard and make money, and to save up to build a home for them in post-civil war Liberia.

But time and distance and misunderstanding took their toll. Eventually, Troh and Duncan married other people and moved on with their lives.

But time and distance and misunderstanding took their toll. Eventually, Troh and Duncan married other people and moved on with their lives.

In early 2014, one of Troh’s daughters, Kebeh Jallah, died giving birth to a child in Liberia. Her death left Troh disconsolate. By then, Troh and Duncan were single again. Karsiah’s high school graduation was coming up. He pleaded with his father to come to America to comfort his mother and to attend his graduation.

Duncan’s visa didn’t arrive in time for Karsiah’s commencement. But he arrived a few months later, Sept. 20, 2014.

By then, the Ebola epidemic raged in Liberia and other parts of West Africa. News accounts horrified the world, describing the wildfire spread of the virus and painful, violent death.

Troh repeatedly insists Duncan did not know the pregnant neighbor he tried to transport to a Liberian hospital died of Ebola. Liberian women die in childbirth all the time. He answered “no” when asked if he had been exposed to the virus. Health officials checked his temperature before allowing him on a plane, heading to America. He arrived at Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport, apparently the picture of health.

Troh repeatedly insists Duncan did not know the pregnant neighbor he tried to transport to a Liberian hospital died of Ebola. Liberian women die in childbirth all the time. He answered “no” when asked if he had been exposed to the virus. Health officials checked his temperature before allowing him on a plane, heading to America. He arrived at Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport, apparently the picture of health.

Duncan talked non-stop about marrying Troh. Their future — finally together — seemed bright.

Within days, Duncan developed a fever, weakness and pain. Troh drove him to the emergency room. He didn’t present the dominant signs of Ebola, vomiting and diarrhea, and medical workers misdiagnosed his illness. By the time they got it right, the virus ravaged his body. Doctors placed him in isolation, and Troh never saw the love of her life again.

But the rest of the world certainly did. Duncan’s picture appeared in practically every media outlet around the globe. His was the face of Ebola in America. He sparked worldwide controversy for “bringing” Ebola to the United States while he suffered and died alone.

But the rest of the world certainly did. Duncan’s picture appeared in practically every media outlet around the globe. His was the face of Ebola in America. He sparked worldwide controversy for “bringing” Ebola to the United States while he suffered and died alone.

Reporters besieged Troh’s Vickery Meadows apartment, where she was quarantined with her youngest son, Timothy, and two nephews. They became pariahs, as fear trumped reason and suspicion surpassed science.

Through her own grief, fear and confusion, heroes emerge in Troh’s story.

Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins worried about Troh, Timothy and the others living in the apartment where Duncan came down with Ebola.

Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins worried about Troh, Timothy and the others living in the apartment where Duncan came down with Ebola.

“We need to get you another place to stay,” Jenkins told her. “I’m going to take care of you like you were my own family. Don’t worry about anything.”

Jenkin’s care for Troh and her family cost his own family. Dallas residents ranted about him in the media. Protesters picketed his home. Someone called his daughter “disgusting.” The local school turned his wife away from her regular volunteer duties.

But Jenkins persisted, visiting Troh regularly. He teamed with Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings and, later, Catholic Bishop Kevin Farrell to find safe, secluded quarantine quarters. He even drove them there himself.

Troh’s pastor, George Mason, provided love, spiritual comfort, counsel in responding to media and, ultimately, a new home.

Mason, pastor of Wilshire Baptist Church, a predominantly white, middle-class Dallas congregation, visited Troh almost every day. Since health guidelines required him to stay at least three feet from her, Mason invented their “quarantine hug.” They crossed their arms over their chests and patted their hands on their chests, signaling their care and concern.

“Every day, Pastor George came to see us,” Troh writes of her three-week quarantine.

“‘Don’t you have a home to go to? Aren’t people in your family afraid that you are here all the time? …” she asked him.

“Oh, Louise, I just have to come here,” he told her.

After the quarantine, Mason worked with Wilshire members to find a home for Troh, Timothy and her nephews. He encountered fear, prejudice and multiple turn-downs, but ultimately persevered.

Eric Duncan had Ebola. Eric Duncan was not Ebola.

Members of Wilshire Baptist mirrored their pastor’s love. Troh had joined the church and was baptized only months before Duncan and Ebola came calling.

But in word and deed, they echoed what Mason told the media: “Louise is one of us. … Louise is our sister in Christ. We love her. And we will be there for her in this terrible time.”

Troh testifies they were there for her, particularly the Open Bible Class, the senior-adult Sunday school group that embraced her before, during and after the crisis.

Troh recounts words Mason spoke at a memorial service for Duncan as wisdom borne of grief.

“Eric Duncan had Ebola. Eric Duncan was not Ebola. Person more than patient. Man more than disease,” Mason said.

“Over and over, Louise used spiritual language to talk about her sadness and grief,” he added. “We said in the quarantine house how we all acted in response to this would be a witness. When she spoke of forgiveness and mercy, compassion and kindness, leaving vengeance to God and judgment to heaven, she did so because she saw Eric’s death and her suffering from inside the story of Christ. The light of Christ has shone from within, chasing away the darkness.”

“Yes, yes, Pastor George, that is how it was,” Troh added. “The words of the Bible are truth.”

My Spirit Took You In: The Romance that Sparked an Epidemic of Fear by Louise Troh with Christine Wicker (Weinstein Books)

Troh and Wicker will share their story at the annual Friends of Baptist News Global Dinner on June 18 during the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship General Assembly in Dallas. The two will participate in a Q&A session with Mark Wingfield, associate pastor at Wilshire Baptist Church and a member of BNG’s board of directors. Wingfield is a former Baptist journalist who found an unexpected role as a spokesman for Louise and her family with the international media last fall. The authors will be available to sign copies of their book immediately following the dinner. Additional information will be available soon on the BNG website.