By Bob Allen

Most histories of the Southern Baptist Convention controversy in the late 20th century downplay or neglect the impact and role of women, a female historian says in a recent book.

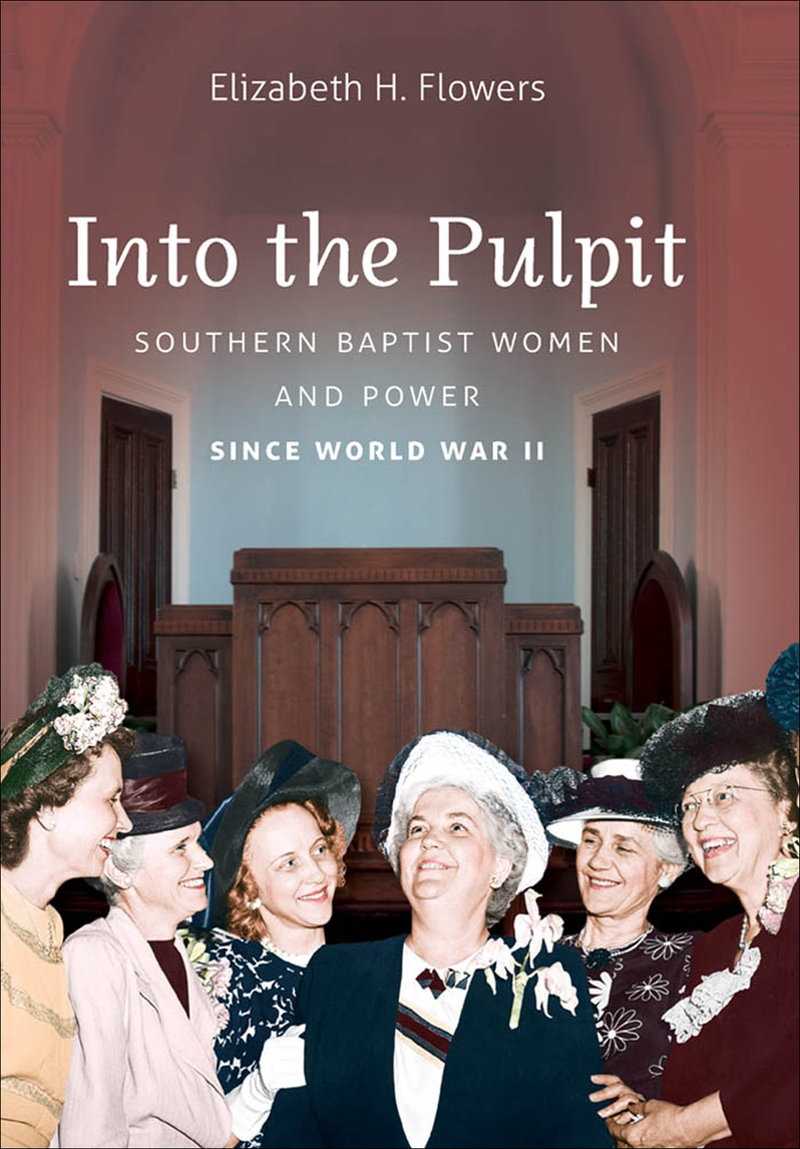

Elizabeth Flowers, associate professor of religion at Texas Christian University, argues in Into the Pulpit: Southern Baptist Women and Power Since World War II, that studies focused on male-led controversies over doctrine and polity miss a larger story.

Elizabeth Flowers, associate professor of religion at Texas Christian University, argues in Into the Pulpit: Southern Baptist Women and Power Since World War II, that studies focused on male-led controversies over doctrine and polity miss a larger story.

While social movements like women’s liberation and the rise of the Religious Right coincided with the SBC controversy, Flowers says most historians have tended to view them as peripheral issues to male-dominated arguments over biblical interpretation and polity. For the more than half of Southern Baptists who happened to be women, she contends in the book, “disagreements that touched on familial roles and ecclesiastical authority were not secondary.”

Flowers says both “the prodigal daughters” who opposed limits placed on women and “the savvy submissive mothers and wives” who could no longer view women’s ordination apart from feminism, abortion, the Equal Rights Amendment and other liberal causes deemed “anti-family” by the Religious Right have been “persistently downplayed and neglected” in one of the most analyzed events in the history of American religion.

Flowers presents women “as major characters in the denominational controversy” and the major story of her book.

Rather than one of a laundry list of differing points of view, Flowers said the women’s issue actually “drove Southern Baptists to embrace certain biblical interpretations over others.” That includes both those women educated in SBC seminaries in the 1970s and 1980s who fought against tradition in breakaway groups like the Alliance of Baptists and Cooperative Fellowship and the “complementarian” movement formed in reaction to the sexual revolution.

Rather than one of a laundry list of differing points of view, Flowers said the women’s issue actually “drove Southern Baptists to embrace certain biblical interpretations over others.” That includes both those women educated in SBC seminaries in the 1970s and 1980s who fought against tradition in breakaway groups like the Alliance of Baptists and Cooperative Fellowship and the “complementarian” movement formed in reaction to the sexual revolution.

“In this book, I argue that as Southern Baptist moderates and conservatives fought for control of the denomination, the issue of women’s changing roles and their bid toward greater ecclesial power moved from the sides to the center of the controversy,” she wrote in the introduction.

Flowers, a graduate of Millsaps College with a master of divinity degree from Princeton Theological Seminary and doctorate from Duke, grew up in a church-going Southern Baptist family, active in youth programs of Woman’s Missionary Union.

“As far as my friends and I were concerned, women led our congregation,” she recalled in the book. It wasn’t until much later she realized that when it came to formal leadership, “they remained on the institutional fringe.”

Flowers distanced from her Southern Baptist background her senior year in high school, after her local association dis-fellowshipped a church for calling a woman as pastor, and her own congregation became divided over the issue.

After attending a Methodist college, Presbyterian seminary and secular graduate school, she revisited the Southern Baptist story by first turning to the grassroots women she had known as a child.

Over a two-year period Flowers attended nine women’s conferences and retreats and a half dozen national meetings, dinners and gatherings. She participated in numerous local church groups, Bible studies, fellowships and mission meetings.

She attended one annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention and three Cooperative Baptist Fellowship assemblies. After writing the manuscript, she returned to some of those venues to talk again to both moderate and conservative Baptist women.

In addition to field work, she made several excursions for archival and textual research.

Flowers said one thing she discovered in talking about the book is a network of 20 to 30 women academics like herself, who share a common faith background of nurture in Southern Baptist churches that motivated their professional callings and academic work outside the denominational structure. They call themselves “GAs Gone Bad,” based on a generation reference to a WMU program for grades 1-6 called Girls’ Auxiliary or Girls in Action.

First published by the University of North Carolina Press in 2012, Into the Pulpit was named by The Christian Century as one of the year’s 10 best “take and read” scholarly books in the category of Global Christianity and American Religious History.

It has been required reading in seminary and divinity school classrooms, including Baylor University’s Truett Seminary and Mercer University’s McAfee School of Theology as well as non-Baptist institutions like Duke Divinity School. Recently the book came out in paperback, making it more readily available and affordable to a general audience. Now Sunday school classes and church groups are picking it up, a development Flowers views as “particularly exciting.”

“I am not only an academic researching and writing about Baptists as they symbolize, influence and reflect wider American culture, but I am also a Baptist woman, dedicated to teaching my Sunday school class and eager to advance the literal and figurative mothers and grandmothers who formed my faith,” she said in an email.

“In other words, I would very much like to see my scholarship in service of the church,” she said.