Forget about politically motivated churches, practices and creeds. Instead, you can learn a lot about religion in North America by the popular books it publishes.

I’ve worked in commercial religious publishing for most of my career and can tell you it’s all about popular books, and there is a lot of power and money in it. Just look at the early 2000s, when the big publishers were buying up evangelical publishers or starting new ones.

David Morris

As Brown University religion professor Daniel Vaca argues in Evangelicals Incorporated: Books and the Business of Religion in America, evangelical publishers historically provided the cultural and social container for a fluid, fractious religious identity in America. These publishers and their “Christian” bookstores reached such a critical mass of capital, infrastructure and content that you’d even find mainline churches using Beth Moore Bible studies and celebrities like Matthew McConaughey reading Lee Strobel’s armchair apologetics.

Outside of evangelical publishing, the businesses around and popularity of books in religion generally pale by comparison. There are publishers representing other religions in the U.S., but even the combined revenue of publishers representing mainline Protestantism does not come close to the evangelical book business.

An exception to the rule

That said, one publisher is a key exception.

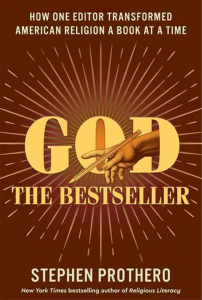

Stephen Prothero

Written by Boston University professor of religion Stephen Prothero, God the Bestseller: How One Editor Transformed American Religion a Book at a Time tells the story of Eugene Exman who, after studying religion at the University of Chicago, found a job working as the religion editor for Harper. Through the 1920s to the 1960s, Exman published or helped publish a compendium of notables such as Harry Emerson Fosdick, Dorothy Day, Albert Schweitzer, Martin Luther King Jr., and Alcoholics Anonymous co-founder Bill Wilson, each warranting a chapter in the Prothero’s book.

The stories Prothero uncovers about Exman are the result of a chance Cape Cod encounter between Prothero and one of Exman’s elderly children, an encounter that led to years of extraordinary archival work that could not have come at any small expense. To varying degrees, each of the figures mentioned above, and others Exman published like Howard Thurman, Aldous Huxley, D.T. Suzuki and Mircea Eliade, represent a quest to publish an anthology of experiential rather than creedal, fundamentalist religion.

“Much of this quest came from Exman’s desire to recapture an early life mystical experience of his own.”

According to Prothero, much of this quest came from Exman’s desire to recapture an early life mystical experience of his own. More broadly, it was a harkening to Harvard philosopher and psychologist William James and the influence of his early 20th century book The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature.

James put focus on the individual experience of religion. He offered a study of personal experience regardless of religious tradition. He also made the claim that religion, or spirituality, is our highest pursuit.

James represents a middle- to highbrow movement in U.S. religion that is both mystical and analytical, with an equal part of humanistic, self-actualizing psychology added in. It is no small matter that James is mentioned throughout Prothero’s book.

Chapter emphases

Each of the chapters in one way or another supports Prothero’s thesis about Exman’s pursuit of religious experience.

The beginning chapter on Riverside Church pastor Henry Emerson Fosdick, who was famous for his 1922 sermon “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” and authored a sermon collection called On Being a Real Person, takes up Fosdick’s emphasis on unhappiness and how religion’s value is how it helps us be truly human.

The chapter on Dorothy Day shows how the founder of the Catholic Worker Movement and author of The Long Loneliness offered an emphasis on personal spirituality without losing site of community and activism.

The final chapter discusses Bill Wilson, who co-founded Alcoholics Anonymous and published the “Big Book” of stories and AA principles. He understood religion to be therapeutic and that to overcome alcoholism one needed religion, but it did not matter which one.

“The chapter on Martin Luther King Jr. is perhaps the most fascinating … because of the considerable behind-the-scenes story it tells about acquiring King’s Strive Toward Freedom.”

The chapter on Martin Luther King Jr. is perhaps the most fascinating, especially to me as a publishing professional because of the considerable behind-the-scenes story it tells about acquiring King’s Strive Toward Freedom, and the level of editing and collaborative writing involved. Although this chapter perhaps contributes the least to the overall thesis of the book, it is an indispensable part of Exman’s story. It shows, if not exposes, the passivity of mid-century white liberals and publishing executives like Exman who wanted Strive Toward Freedom to be a paean to human brotherhood, when instead King wanted a book that was more a prophetic warning.

Eugene Exman

Also included is a chapter on Exman’s associate Marguerite Bro, who not only did most of the editorial heavy lifting but also was Exman’s equal in terms of acquisitions acumen. And there is a chapter on the fleeting religious retreat center in Trabuco Canyon, Calif., meant to foster conversations and contemplative experience.

There’s no questioning that Exman’s publishing singularly elevated a conversation about religion that went well beyond the dominant denominational and confessional publishing in the United States. Exman’s authors talked about religion and spirituality in a way that was likely free from so much theological exceptionalism. These were books pointing to the universality of religion and validating individual, even mystical experience.

What’s missing

Although Prothero’s book is as much priceless ethnography as it is religious commentary, I wish it were just a bit more commentary. So much of God the Bestseller juxtaposes the institutions of religion with a religion of individual experience and serves as a defense for the latter. No doubt, there is an entire stream of American religion that is more mystical or transcendental that has been around for a long time and has experienced widening growth. Yet what seems overlooked in this kind of juxtaposition is that personal experience features deeply in U.S. religion whether it’s channeled through institutions or individuals. In other words, it’s all more individualistic than it is communal.

Cloaked by the emphasis on creeds, theology and apologetics, consider key evangelical features like individual conversion and salvation, a “personal relationship with God,” megachurch worship music and especially the ecstatic ritualizations of charismatic style churches or, alternatively, the fervor of a Trump political rally, as Jeff Sharlett points out in his recent book The Undertow. These are more street-level expressions of religion, less esoteric and educated than so many of Exman’s authors.

“In the U.S. we’ve in fact created, ironically, churches of individualism, where we prioritize experience of God over ethical relationship and flexible, lasting community.”

I would argue that in the U.S. we’ve in fact created, ironically, churches of individualism, where we prioritize experience of God over ethical relationship and flexible, lasting community. Just think of all the church splits. What Exman’s publishing work represents is often more of the same individualism, only through a more affluent, book-reading cohort.

But if we are to shift away from the U.S. social club of evangelicalism, the books we read can help find the way. Interestingly, HarperOne, the imprint with the Exman legacy, seems to be making a shift more to self-help and away from historically formal U.S. religious culture. While they’ve been known as the caretakers of the C.S. Lewis library, one of their biggest recent bestsellers is the Subtle Art of Not Giving a F**ck. Also notice their books on Tarot, books that, by the way, are finding traction with former evangelicals. But even still, the days of bestselling books by major, mostly male, religious thinkers are over.

Likewise, the halcyon days of evangelical publishing are over. The bulk of their bookstores are gone. Their publishers are fighting for the scarce large author platforms that will pay for their overhead handcuffs while church attendance declines and more people are claiming “none” as their religious affiliation.

Likewise, the halcyon days of evangelical publishing are over. The bulk of their bookstores are gone. Their publishers are fighting for the scarce large author platforms that will pay for their overhead handcuffs while church attendance declines and more people are claiming “none” as their religious affiliation.

So that means we’re entering a time religiously where nothing is the same as it was before. We’ll continue to see experiential religion and individualistic belief as a key feature of U.S. culture. And if religion is the ultimate expression of human experience, as James argues psychologically, we must ask ourselves whether it really goes away, or do we find it by some shift in our epistemological understanding of religion and spirituality. Maybe, for example, we find it in the new local cultures we have online, or in the new urban centers where remote workers are moving.

We know, nevertheless, that we have much to draw on and a rich history of religion and spirituality that need not be connected to the monolithic politics and commerce of evangelicalism. The questions are, who are the authors helping us discover our new artifacts of faith, what are their books, and who is publishing them?

David Morris is the author of Lost Faith and Wandering Souls: A Psychology of Disillusionment, Mourning, and the Return of Hope. He is the publisher of Lake Drive Books and a literary agent at Hyponymous Consulting, two ventures working together to specialize in authors and books that help people heal, grow and discover. David holds a Ph.D. in psychology and religion from Drew University. He lives with his wife in Grand Rapids, Mich. More at davidrmorris.me.