Note: This is the fourth in a five-part series on the Black Gospel Music Preservation Program made possible by generous funding from the Prichard Family Foundation.

Black gospel music has a cross-cultural appeal that can help bridge racial divides that in the 21st century still threaten the fabric of our society, according to scholars working to preserve the music for future generations.

Speaking from the Black Gospel Music Preservation Program at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, founder Robert Darden said there is something in the music that resonates with people who do not come from that tradition.

Robert Darden

“When you think of the music that has had world appeal, that’s come from America, it’s always the music that comes from the Black community — jazz and the blues,” he said. “But when you add that sacred element to it, then there’s a resonance to people, I think, that cuts through not just racial and socio-economic and intellectual barriers, but something a whole lot deeper. And it may be something inherent in the music itself coming from the motherland in Africa.”

Darden said the power of Black gospel music to unite is not unlike the way early rock-n-roll music helped dismantle barriers between Blacks and whites and especially among youth.

“Chubby Checker and Little Richard and whoever would play, and there would be a rope between the white and the Black dance floor, and at some point the rope would come out and kids would dance. And the white kids would dig how the Black kids were dancing and want to do that,” he said. “I think that’s a good analogy for Black gospel music, because very early on, white musicians began long before the rest of the community to realize the worth of this and the value of this and how much they had to learn.”

“There’s always a transition zone, it seems in America, where white and Black come together, and those places are in entertainment and in the church.”

He continued: “There’s always a transition zone, it seems in America, where white and Black come together, and those places are in entertainment and in the church. And gospel music combines both of those. Not to be coy here, but gospel music is entertaining. It’s the most emotional of all the major religious music forms, but it is also the most theatrical — even more than opera, which is so stylized in some ways. You never know what a gospel concert is going to be. That level of spontaneity and Spirit-driven enthusiasm and joy is incredibly appealing and seductive.”

Darden, who in 2023 retired from Baylor’s journalism department as professor emeritus, launched the gospel music project in 2006 to preserve a genre of music he loved and was writing about but had trouble finding. Today, the program is the world’s largest initiative to identify, acquire, digitize, catalog and make available America’s fast-vanishing legacy of vinyl records from the “golden age” of gospel music — roughly 1945 to 1975.

The collection — encompassing 5,000 vinyl records on the shelves and 48,000 digitized tracks — is accessible in person through a state-of-the-art listening center at Baylor’s Moody Memorial Library. Digitized recordings may be heard from anywhere via the library’s online digital collection. The program partners with the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

The collection is visited by scholars doing research and fans who just want to listen. Among the Baylor Libraries’ more than 70 digital collections, it is ranked in the top five for gaining the most interest.

Henry Louis Gates Jr., a nationally known historian familiar to audiences of PBS’ Finding Your Roots, tapped Darden and the archives for his 2021 documentary, The Black Church: This is Our Story, This is Our Song. He returned to Waco more recently while researching Gospel, which will air on PBS in February 2024 in four installments.

“The music is sanctified. It’s bathed in the Spirit, and you would have to be a really dead soul not to somehow resonate with that.”

“Music, particularly Black sacred music, has the unique property, it seems to me, of breaking down barriers faster and more effectively than anything else,” Darden said. “The music is sanctified. It’s bathed in the Spirit, and you would have to be a really dead soul not to somehow resonate with that.”

Music to unite on Sundays

With Darden’s retirement, the program is led by Steven Newby, formerly at Seattle Pacific University, who in July was named the inaugural Lev H. Prichard III Chair in the Study of Black Worship at Baylor. Newby, himself a composer of music in various genres and a worship pastor for 25 years at a multi-ethnic church in the Seattle area, said a key to the process of building cultural and racial bridges is listening and learning.

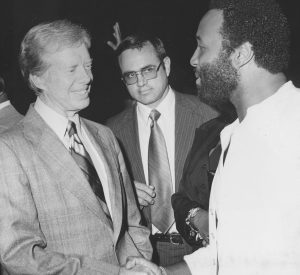

The soul and gospel singer Andrae Crouch at the White House salute to Black music, meeting President and Mrs Carter, in honor of the Black Music Association, Washington, D.C.,, 1977. (Photo by Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images)

“There are some churches, whether they’re homogeneous white or homogeneous Black, that sometimes can’t get to that multi-ethnic space because they’re not willing to do the heavy lifting in someone else’s culture,” he said.

He gave the example of an African American church that presents an excellent performance of excerpts from Bach’s St. Matthew Passion because they’ve done “the heavy lifting” of learning the music in the German language.

“I would challenge congregations that are non-Black to explore Black gospel music and import it into their liturgies,” he said. “Now, it’s not appropriation when you are moving toward a kingdom of God — like what is heaven going to look like? — and you want your church to look like that. But if you don’t want your church to look like that, then perhaps you’re looking at the music for the wrong reason.”

The key, Newby said, is not just to perform the music but to learn from it.

“The greatest miracle that can happen is God changing a heart of hatred.”

“It is really important for people to listen to each other’s stories. This music is God stuff, and if non-Black congregations decide to pay attention to it, and then they want to expand their idea of what their churches look like, watch out, because miracles will take place,” he said. “And the greatest miracle that can happen is God changing a heart of hatred. That’s the greatest miracle. It’s not curing cancer. It’s not ending famine or drought. It’s God changing a human heart.

“Even Martin Luther King Jr. said hatred and bitterness can never cure the disease of fear. Only love can do that. Hopefully people will fall in love with the music as a way to open the door to fall in love with the people. And that is, I think, a pathway forward for radical reconciliation: Reconciliation with the planet, reconciliation with humanity, and reconciliation to the wise creator. And it happens in reverse order. Wise Creator, humanity, then the earth will heal.”

Music that still moves

Darden said as he watched news coverage of the Black Lives Matter protests in 2022, he saw people singing songs from the 1960s Civil Rights movement who were much too young to have experienced that movement firsthand. He said the same has been reported from other social and political movements, whether it was at Tiananmen Square in 1989 or the Arab Spring of the early 2010s.

“I kept asking myself, ‘What is it that has enabled this music to endure?’ The music endures because it’s anointed. It endures because it works and it works because God has blessed it,” he said. “And the lyrics survive. A, they’re easy to sing, you don’t need a hymnal, and B, I believe that since the days of the enslaved people, those songs have been through the flame and all the dross has been burned away. All that’s left are the words that are closest to the heart cry.”

Darden said the universal appeal of the music — as an art form but also in the spirit and messages it delivers — has helped draw interest in the archive not only from scholars and fans but from individuals who want to provide financial support to expand its resources.

“If it’s easy for me to explain it even to bureaucrats and administrators and accountants who don’t have any background in this, who have on their own come forward to support this out of many worthy causes, then all I have to figure is that this is pleasing to God,” he said.

Previous articles in this series:

Black gospel music has messages hidden in the grooves

Around the world and back: The enduring influence of Black gospel music

Black Gospel Music Preservation Program: Securing the legacy of Black Gospel music