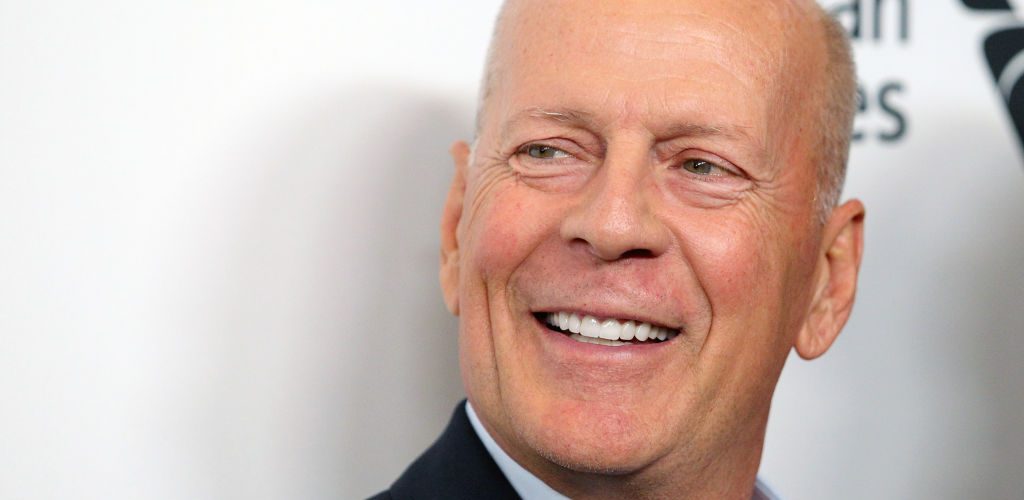

Actor Bruce Willis has been diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia, or FTD, his family announced Feb. 16. The disease, also known as frontotemporal lobar degeneration, has no treatment or cure.

“While this is painful, it is a relief to finally have a clear diagnosis,” Willis’ family said in a statement posted on the website for the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration. “FTD is a cruel disease that many of us have never heard of and can strike anyone.”

Frontotemporal dementia is a category of neurodegenerative diseases in the same family as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s. About 50,000 to 60,000 people in the United States have FTD.

FTD differs from other types of dementia in the typical age of onset. It is most common among people under 60.

FTD affects specific areas of the brain — the frontal and temporal lobes — leading to changes in behaviors, speech and some motor skills. Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, the risk of frontotemporal dementia does not increase with age.

I reached out to Lynn Casteel Harper, minister of older adults at the Riverside Church in New York City and author of On Vanishing: Mortality, Dementia, and What It Means to Disappear, regarding Willis’ condition and how faith communities can respond pastorally to people with this and other forms of dementia.

Others withdraw

“Churches are highly relational, focused on formal and informal modes of supporting one another through life’s various passages,” she noted. “People living with dementia and their loved ones experience stigma and the diminishment of their social circles. Friends, family — even the church — withdraws from them.”

Harper encourages churches to stay connected to people living with dementia and their loved ones by strengthening existing relationships rather than by creating new programs. Listening to congregants and their families about what is important to them is a good place to begin. From there, churches can consider what resources to bring to bear on the situation.

“Our involvement in our faith communities shouldn’t revolve around anyone’s verbal or written fluency or an unchanged personality.”

“Our faith traditions don’t rise or fall on the executive functions of members’ individual brains,” Harper said. “We sing hymns, enjoy the organ or other instruments, take communion, pray familiar prayers, hear the poetry of Scripture, shake hands, hug, eat together.”

“FTD often impacts one’s ability to speak and write — and may impact one’s personality. But our involvement in our faith communities shouldn’t revolve around anyone’s verbal or written fluency or an unchanged personality.”

Churches also can educate their congregants about dementia-producing illnesses by partnering with their local Alzheimer’s Association chapter to offer programs. Online education resources are also available from the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America. Another good resource is Memory Bridge, an organization that seeks to end the emotional isolation many people with dementia and their loved ones experience when verbal communication breaks down.

Listen and stay in relationship

“While it is helpful to learn about the medical aspects of different diagnoses, equally important is listening to and staying in relationship with people living with the condition and their loved ones,” Harper said. “No one wants to be identified just by their disease or their deficits, so I think it’s really important to keep each person’s individuality in view — and their sacred worth.”

In Dementia: Living in the Memories of God, John Swinton challenges readers to set the standard for “a truly Christian understanding of dementia and the development of authentically Christian modes of dementia care.”

Swinton, professor of practical theology and pastoral care at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and founding director of the Centre for Spirituality, Health and Disability at Aberdeen, notes, “well-being within Christianity is not gauged by the presence or absence of illness or distress.” Rather, “well-being, peace, health — what Scripture describes as shalom — has to do with the presence of a specific God in particular places who engages in personal relationships with unique individuals for formative purposes.”

Creating space for people with dementia and their loved ones in the life of the church … is part of the broader work of improving religious access for people living with disabilities.

For Swinton, dementia is a thoroughly theological condition, one that cannot be adequately understood or described by standard neurobiological explanations. “It makes a world of difference to suggest that dementia happens to people who are loved by God, who are made in God’s image, and who reside within creation,” he said.

Creating space

Creating space for people with dementia and their loved ones in the life of the church, providing a caring and supportive environment for all, is part of the broader work of improving religious access for people living with disabilities.

Many churches have been slow to embrace this opportunity — treating people with disabilities as objects of charity rather than as integral participants and partners in the life of the community of faith, individuals with unique gifts, talents, strengths and insights.

“If churches cultivate practices of community and care, focusing on embodied rituals and spiritual companionship — not based on intellectual activities and abilities — then we are taking big steps toward being spaces where people like Bruce Willis and so many others are received with joy,” Harper said.

“If the church is the body of Christ, all members of one another, then we are only whole when people living with dementia and their gifts are welcomed too.”

Curtis Ramsey-Lucas

Curtis Ramsey-Lucas is editor of The Christian Citizen.

Related articles:

Faced with a frightening dream, my father with dementia showed me the way

Till death (or illness or dementia) us do part?