The problem with white evangelicals isn’t their close affiliation with the Republican Party but the homogeneity of their political thinking and culture, sociologist of religion Ryan Burge said during a conference hosted by Denver Seminary.

“When a religious movement becomes overwhelmingly a political monoculture, that’s bad not just for the people in the pews, but for democracy as a whole,” said Burge, associate professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University and author of the “Graphs about Religion” Substack.

“We need to be around people who are different than us, and whatever church you’re in, if everyone you sit next to on Sunday mornings votes the same way that you do, then you’re failing what it means to be a kingdom-centered church, and you’re also making it harder for us to live in a functioning democracy.”

Ryan Burge

Burge delivered one of five keynote addresses during “Compelling and Credible Witness: The Church and Politics.” The September event also featured presentations by journalist and author Tim Alberta; Native American activist Mark Charles; political strategist, attorney and minister Justin Giboney; and Denver Seminary President Mark Young.

Burge focused his talk on the state of American religious groups and their political leanings, including the Mainline, nondenominational, the Catholic Church and the religiously unaffiliated also known as nones.

Among white evangelicals, 20% identify as Democrats and 60% as Republicans, but a full 80% will vote for Donald Trump on Nov. 5, which demonstrates the near total political alignment of Christian conservatives regardless of party, he said.

“The reason I know that is because in 2020, 80% of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump, but here’s what no one tells you about that: in 2008, 80% of white evangelicals voted for John McCain and in 2012, 80% of white evangelicals voted for Mitt Romney,” said Burge, author of The Nones and a contributor to The Great Dechurching: Who’s Leaving, Why They are Going, and What Will It Take to Bring Them Back?

The share of Americans who embrace the evangelical label (around 27%) is lower than the 30% peak reached in 1994 but higher than the 17% to 23% range that followed.

Evangelicalism also has become more disconnected due to the rise of the nondenominational church movement that essentially ended the monopoly enjoyed by large evangelical denominations like the Southern Baptist Convention, he added. “Now there are all these little pockets of evangelicalism all around America and they don’t talk to each other.”

But that separation hasn’t kept evangelicals from thinking and voting in lockstep and from moving so far to the right culturally and theologically that dyed-in-the-wool evangelicals like Russel Moore, David French and Beth Moore are labeled as liberals for questioning or criticizing Trump. And it’s not stopping there, Burge said.

“The Southern Baptist Convention has lost 3 million people over the last 16 years, so there’s a whole movement inside the SBC to right the ship. You know what their whole motivation is? The denomination has become too liberal.”

Resolutions are brewing in the SBC to oppose in vitro fertilization and to proclaim abortion as murder and that those who seek abortions should be imprisoned, even though only 20% of evangelicals oppose IVF and only 20% agree abortion seekers should be jailed.

“I don’t know what it is about religious movements, but they love to purify themselves and it’s killing us.”

“The thought leaders in these denominations are telling 80% of their own people that they are too liberal to be in their denomination,” Burge said. “I don’t know what it is about religious movements, but they love to purify themselves and it’s killing us.”

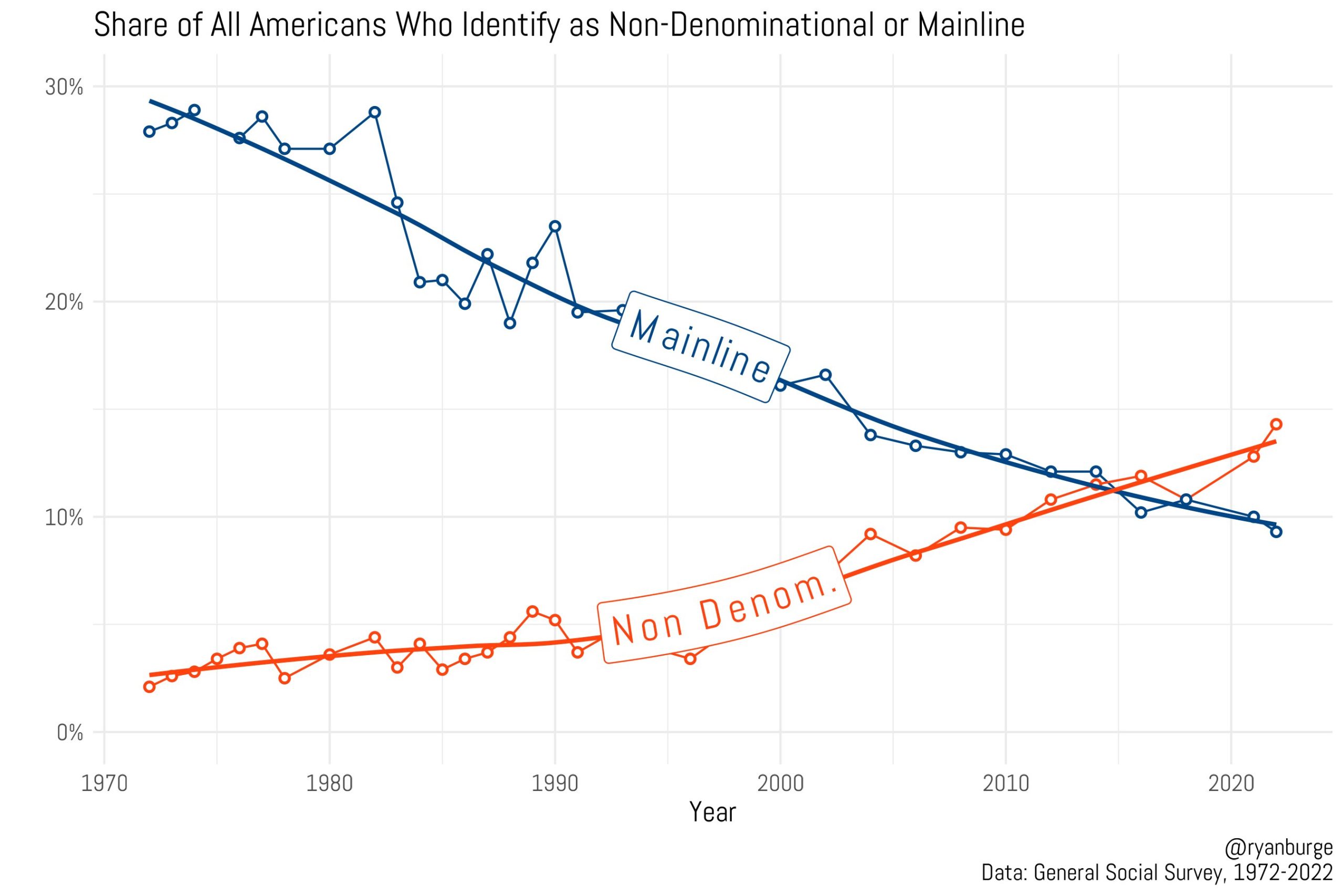

While it’s no surprise anymore that white, mostly moderate or liberal Mainline Protestant Christianity is waning, just how steeply and rapidly they have declined has been largely overlooked, Burge said of the United Methodist Church, Episcopal Church, United Church of Christ, Disciples of Christ, Evangelical Lutheran Church, Presbyterian Church (USA) and American Baptist Churches USA.

About 55% of all Americans were on the membership rolls of one of those denominations in the late 1950s. That number plummeted to 30% by the early 1970s, fell below 20% by 1988, then 10% by 2018 and today stands around 9%.

“These were denominations that used to hold enormous cultural power, political power, religious power. They steered the ship. They could point people to the right candidate. I could say this is the kind of Christianity we want. These are people who focused on things like the Social Gospel, that worked on reconciliation and compromise, that welcomed people from the left, right and center into their churches.”

There is little hope they will rebound because the share of Mainline Protestants between 18 and 40 years of age represents a mere 2% of Americans. Half of Episcopalians, for example, have celebrated their 65th birthdays, while only 17% are 18 or younger, he said.

“If they kept every child that is in church right now, in 30 years they would be 37% smaller than what they are today — and they are not going to keep every child. They might keep half of them, if they’re lucky. So, the Episcopal Church will be 45% smaller in 30 years than it is today, and it’s already down to 325,000.”

Most conservatives abandoned Mainline churches long ago, and many liberals have joined the ranks of the nones, Burge added. “There is no white, Protestant, liberal tradition in America today of any consequence. To be a white Christian is to be a conservative by default.”

Many of those white Christians are part of the nondenominational movement that has grown from 3% of U.S. adults in 1972 to 15% in 2024. “They are the fastest growing religious force in America today, and they are overwhelmingly Republican,” Burge said.

White Catholics also are majority Republican, with 60% voting for Trump in 2020. “And all the tracking polls say that’s going to be the same thing happening in 2024.”

The bottom line is the young, liberal Catholic priest is a thing of the past.

As a whole, the U.S. Catholic Church is trending further and further to the right. Among priests ordained before 1981, 38% are Democrats, 24% are Republicans and 38% independent. “But with every passing decade of ordination, you can see the priests coming into the Catholic Church are becoming more and more conservative,” Burge noted.

Two-thirds of those ordained in the past 20 years identify as conservative and almost none as liberals. The bottom line is the young, liberal Catholic priest is a thing of the past, Burge declared. “I think about the young Catholic who reads about (the late social activist) Dorothy Day. He goes, ‘I want to be like that’ and goes to mass every Sunday and hears nothing about Catholic activism, about immigration, about workers’ rights. All they hear is more culture war stuff.”

Nones — Americans who are religiously unaffiliated — seemed to have stopped growing and currently represent 30% of the population, Burge said. Made up of agnostics, atheists and those who say they are “nothing in particular,” they tend to be among the most liberal and the most likely to support transgender care for those under age 18.

“They are people who will tell you that not only am I not religious, that you should not be religious either and that religion is a cancer, that religion is the cause of all the ills facing the world,” Burge explained.

All this adds up to there being no middle ground going forward in the U.S., he concluded. “There will be no space for the moderate, compromising practical person who says, ‘I can see it your way. I’m a Christian, but I believe in a plural of society.’ No, if you’re not a Christian, your vote shouldn’t count on election day. I’ve actually had people tell me only Christians should be able to vote on election day in this country.”

Related articles:

Here’s what I’m learning about the ‘nones’ | Analysis by Mark Wingfield

What to do with the nones? | Opinion by Bill Wilson

Both Mainline Christians and evangelicals lost relevance by seeking power, podcast emphasizes

New book shows how Mainline churches promoted Christian nationalism by another name