In his 2016 landmark book, America’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America, Jim Wallis reveals: “The most controversial sentence I ever wrote was not about abortion, gay marriage, the wars in Vietnam or Iraq, elections, or anything to do with national or church politics. It was a statement about the founding of the United States. Here’s the sentence: ‘The United States of America was established as a white society, founded upon the near genocide of another race and then the enslavement of yet another.’”

It has been four years since Wallis wrote about America’s original sin of racism and white privilege — four years of Donald Trump’s America — four years during which we have been told that Mexicans are “rapists,” Muslims are “sick people,” Latinx immigrants are “animals,” and Africans come from “shithole countries,” that what we need are more immigrants from Scandinavian countries, and that Trump saved the neighborhoods of suburban women by keeping out people of color.

A sin that predates racism

“I believe Wallis is correct about America’s original sin, but I also believe that globally there is a sin that predates racism. That sin is casteism.”

I believe Wallis is correct about America’s original sin, but I also believe that globally there is a sin that predates racism. That sin is casteism. And white, male billionaire Donald Trump commits the sin of casteism brazenly, habitually and rarely without consequence.

Isabel Wilkerson

Isabel Wilkerson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Caste: The Origins of our Discontents, explains the difference between racism and casteism. She writes: “Because caste and race are interwoven in America, it can be hard to separate the two. Any action or institution that mocks, harms, assumes, or attaches inferiority or stereotype on the basis of the social construct of race can be considered racism. Any action or structure that seeks to limit, hold back, or put someone in a defined ranking, seeks to keep someone in their place by elevating or denigrating that person on the basis of that perceived category, can be seen as casteism.”

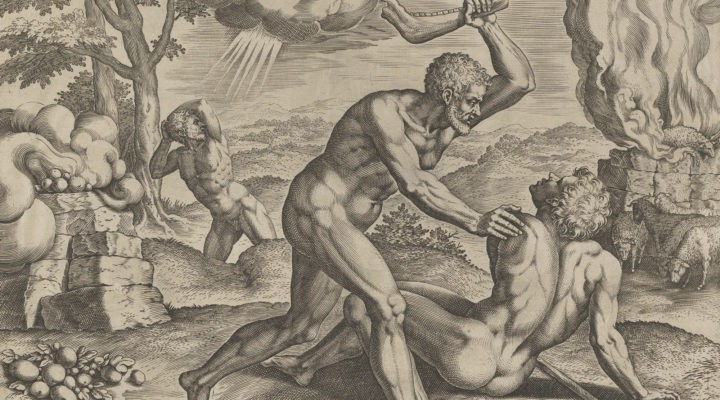

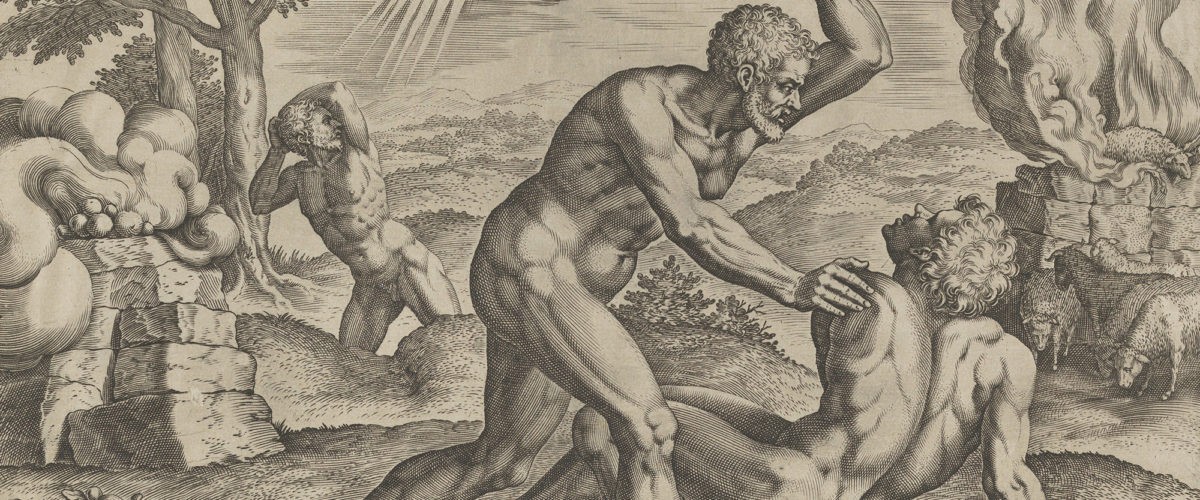

While racism may be America’s original sin, casteism is humanity’s original sin. It is committed in Genesis 4, right after the disobedient act in chapter 3 where Adam and Eve eat the forbidden fruit. But like professor Regina Schwartz of Northwestern University, I do not believe their poor choice in the Garden is the cause of all of the discrimination, aggression and inequality in the world.

Cain and Abel

Regina Schwartz

In her book, The Curse of Cain: The Violent Legacy of Monotheism, Schwartz comments: “Original sin. The wisdom of the ages tells us that all of the miseries of the world — the injustice, hostility, pain, poverty, illness, violence, and even death — are the result of the first man and woman disobeying God. They ate a fruit when he told them not to. I have never been persuaded … . But there is another foundational myth, one that follows on the heels of the story of Adam and Eve, that strikes me as especially appropriate for the violence that rends our world: the story of Cain and Abel.”

The metaphor of the unequal and therefore unjust relationship between Cain and Abel, like that of the self-interested taste of Adam and Eve, is a myth with consequential importance — “mythic” in the anthropological understanding that this story has shaped people’s beliefs and actions long after the event itself occurred.

Bill Moyers

As Baptist journalist and political commentator Bill Moyers declares in Genesis: A Living Conversation: “The Bible is the mother of all books to Western culture. Not only are these stories the source of three great religions, they’ve shaped the imagination and ethics of our culture … . These old stories can point to some common ground for talking about our lives today.”

Cain and Abel were the sons of Adam and Eve. The elder, Cain, tilled the soil while the younger, Abel, shepherded flocks. “In the course of time Cain brought to the Lord an offering of the fruit of the ground, and Abel for his part brought of the firstlings of his flock, their fat portions. And the Lord had regard for Abel and his offering, but for Cain and his offering he had no regard. So Cain was very angry, and his countenance fell” (Genesis 4:3-5).

Feeling cheated

Karen Armstrong

From her book, In the Beginning: A New Interpretation of Genesis, comes the fascinating suggestion by British historian and religionist Karen Armstrong that this episode may have been an attempt to explain the ongoing antagonisms between farmers and ranchers. Millennia later, Rodgers and Hammerstein would popularize this conflict with the playful lyrics: “The farmer and the cowman should be friends, Oh, the farmer and the cowman should be friends. One man likes to push a plow, the other likes to chase a cow, but that’s no reason why they can’t be friends.”

But the dispute between Cain and Abel was no musical comedy. Armstrong notes that the Yahwist writer “has given it a darker, more archetypal significance … . Cain himself could not master his grief and fury.” So Cain enticed Abel to go out into the field with him, and then he unleashed his savage anger and murdered his brother.

Charles Johnson, National Book Award recipient and retired English professor from the University of Washington, dialogues with Moyers, saying: “There’s a sense in which Cain’s crime is more of an original sin than the kind of sexual mistake made by Adam and Eve. Murder enters the human experience, and the murderer becomes the first builder of a city. It’s almost as if to say that this kind of violence — the elimination of the brother, the other, the double — is foundational for the rest of civilization.”

Cain was older, and thus he assumed that he was entitled, that he was the preferred and privileged brother, even in the sight of God. When his younger brother found favor instead, he was enraged — much like Esau with his brother Jacob, or Jacob’s older sons with their younger brother, Joseph. Cain felt left out, cheated, humiliated, devastated and threatened. The Lord asked him, “Why are you angry, and why has your countenance fallen?” (Genesis 4:6) But Cain could not explain how he felt, other than to sense, incredulously, that the order of acceptance and rewards did not match his status.

Ferociousness and fatal competition

These feelings prompted humanity’s original sin — the sin of thinking one is intrinsically more deserving than one’s brother and that something had to be done to right the wrong. Schwartz concludes: “Cain kills in the rage of his exclusion. And the circle is vicious, because Cain is outcast, Abel is murdered, and Cain is cast out. We are the descendants of Cain because we too live in a world where some are cast out, a world in which whatever law of scarcity made that ancient story describe only one sacrifice as acceptable — a scarcity of goods, land, labor or whatever — still prevails to dictate the terms of a ferocious and fatal competition. Some lose.”

“Casteism is the investment in keeping the hierarchy as it is in order to maintain your own ranking, advantage, privilege or to elevate yourself above others or keep others beneath you.”

Wilkerson identifies self-regard that leads to rivalry and often to revenge with the term “casteism.” She explains: “Casteism is the investment in keeping the hierarchy as it is in order to maintain your own ranking, advantage, privilege or to elevate yourself above others or keep others beneath you.”

This sin is based on the faulty assumption of the zero-sum game — the idea, explained by Schwartz, that “one can prosper only at the other’s expense.” The “Cains” of this world can only get what should be theirs, and thus feel justified by putting down the “Abels,” who are somehow more acceptable.

All his life, Donald Trump has felt threatened that his “gift” was not good enough. That sense that he might be losing the competition, whatever it may be, could explain why he constantly works so hard to convince others, or himself, that he is superior. Perhaps his harsh judgments about others and actions toward them are how he strives to maintain his own ranking, advantage, privilege and elevated status. Believing he can only prosper at another’s expense, Trump tries to “kill,” or eliminate, his competition — with lies, insults, deception, collusion, subterfuge and even violence.

We continue the sin of casteism

Jewish rabbi and theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel — in his book Israel: An Echo of Eternity — decried the jealousy and enmity that caused brother to rise up against brother. He argued: “The way that leads out of the darkness is peace between brothers, care for our fellow man.” Yet, in so many ways, we continue the sin of casteism that leads, tragically, to forms of fratricide.

Trump’s loyal followers have likened him to King Cyrus, King David, even King Jesus. Maybe, however, he is much more like Cain.

Yet, the president is merely representative of the ways we all are tempted to commit the sin of caste discrimination — all of us who may feel we are superior and entitled because of our race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, age, position, education, wealth or religion.

In what way, I wonder, is each of us indicted by this archetypal story of Cain and Abel?

Rob Sellers is professor of theology and missions emeritus at Hardin-Simmons University’s Logsdon Seminary in Abilene, Texas. He is the immediate past chair of the board of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. He and his wife, Janie, served a quarter century as missionary teachers in Indonesia. They have two children and five grandchildren.

Rob Sellers is professor of theology and missions emeritus at Hardin-Simmons University’s Logsdon Seminary in Abilene, Texas. He is the immediate past chair of the board of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. He and his wife, Janie, served a quarter century as missionary teachers in Indonesia. They have two children and five grandchildren.