Natasha White spent more than a quarter of a 15-year prison sentence in New York banished to solitary confinement, an experience that inflicted so much emotional and physical trauma that it has shaped the course of her life since her release.

“To this day I self-isolate and I’m very uncomfortable in crowded settings,” White said during a recent Equal Justice USA webinar designed to show churches the brutality of solitary confinement and how they can help oppose the practice.

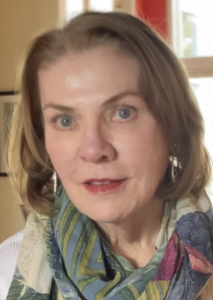

Natasha White

Exacerbating the pain of enforced solitude was the fact that it was her husband’s gang affiliations that landed her in solitary, White said. “I stayed in that exact cell for four years until I was finally transferred to another prison. During that time, I never received a visit, letter or a package from the outside. I literally had no interaction with anyone other than prison staff.”

But the experience also propelled White into full-time activism to eradicate the practice of solitary confinement. She is the Virginia representative for the Unlock the Box national campaign and serves as coordinator of the Virginia Coalition on Solitary Confinement.

“This practice breaks the spirit of people, and it breaks their hearts.”

“I decided to dedicate my life to ending solitary confinement and the torture of incarcerated individuals,” she said. “This practice breaks the spirit of people, and it breaks their hearts.”

The hope is that hearing such stories will convince communities of faith to join in the movement to end solitary confinement, said Sam Heath, manager of EJUSA’s Evangelical Network. “Christians are in the business of seeing and helping people be healed and not perpetuating violence. Solitary confinement is itself an act of violence.”

Sam Heath

Christians follow a Savior who himself was unjustly persecuted by the state criminal justice system of his time, Heath noted. That should instill churches with the compassion and motivation to join the effort.

“To engage Jesus in his call to life is to engage a systemic peace in our world. It is to move into a political space for the love of neighbor,” Heath said. “So, churches have a really unique role in how they can help interrupt the cycle of violence. They can advocate for spaces of healing and restoration that aren’t dependent on punishment.”

Numerous studies have demonstrated the violence solitary confinement wields against its victims, White said. “Self-mutilation and, ultimately, suicide are some of the only ways out.”

Inmates exposed to the practice have a suicide rate 78% higher than the rest of the U.S. population, she said.

And despite progress in some states, the use of solitary confinement has risen 500% since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, she added. More than 300,000 prisoners are subjected “to these cruel and inhumane settings” at any given time.

An inmate looks out a window in his solitary confinement cell at the Main Jail in San Jose, Calif., on Dec. 16, 2019. (AP Photo/Ben Margot, File)

For certain populations, the effects can be even more devastating, White explained. “For persons with serious mental illness, the lack of meaningful social contact and unstructured days can exacerbate symptoms of mental illness or provoke reoccurrences.”

Female prisoners in isolation experience high rates of emotional and sexual abuse from corrections officers and are more susceptible to infections from lack of access to showers and feminine hygiene products, White said.

Prison systems often try to mask the use of the tactic with different names, including special housing, restricted housing and restorative housing. “But any form of isolation for 20 hours or more is solitary confinement,” she said.

White also described solitary confinement as a humanitarian issue. “Those in isolation are at a higher risk of death due to mysterious circumstances. These individuals are left alone with no third party to check on their safety and well-being. They are human beings who have rights and should not be subjected to this dangerous, torturous practice.”

Several states have seen it that way, too — at least partially. A study by the ACLU found that concern about solitary confinement began to rise just before the pandemic.

“In 2019, we saw national momentum to reign in the abusive use of solitary confinement expand faster than ever before,” the report stated. “This year was record-setting in terms of reforms we saw introduced in state legislatures. Twenty-eight states introduced legislation to ban or restrict solitary confinement, and 12 states passed reform legislation: Arkansas, Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, Texas, Washington, and Virginia.”

It continued: “Some of these new laws, such as those in Connecticut and Washington, present tentative and piecemeal approaches to change. But most represent significant reforms to existing practices that promise to facilitate more humane and effective prisons, jails and juvenile detention centers.”

McGennis Williams

Advocates are pushing hard to see similar progress in Virginia, said McGennis Williams, an attorney and chair of the Virginia Coalition on Solitary Confinement.

The organization was founded in 2014 as an alliance of individuals and organizations, including faith-based groups, determined to end Virginia’s open-ended use of solitary confinement.

But it’s been an uphill battle so far, Williams said. “From 2014 to 2022, we introduced bill after bill, and year after year and it didn’t go anywhere.”

Earlier this year, legislation to limit solitary confinement to 15 days in any 60-day period was delayed by a House subcommittee which directed the Virginia Department of Corrections to study its use of the practice.

Williams said the department has stalled on the study, so the coalition is conducting its own research into the trends and abuses of solitary confinement in state prisons to prompt new legislation. “And we’re going to get that bill passed with your help,” she added.

“My cell was dark and smelled like feces. Women banged and screamed all night.”

White pleaded with churches to offer that help because solitary confinement is much more savage than it sounds: “My cell was dark and smelled like feces. Women banged and screamed all night, and there was a woman named Keisha in the cell next to mine who committed suicide. I could hear her gagging and fighting against the sheet she had used to hang herself, with her feet kicking at the wall trying to get a grip. Others mutilated themselves just to get to the clinic. It was horrible. I can still hear their screaming and begging, sometimes, in my dreams.”

Heath said churches should respond to such suffering differently than the wider culture, which often considers the pain and misery of prisoners as justifiable vengeance.

“Part of that is how we think about what justice is,” he explained. “Most of the time when people say the word or think of the word justice, it’s synonymous with punishment. I want us to think about things like safety and healing and accountability — safety of body and of mind, and healing.”

Related articles:

Faith leaders protest use of solitary confinement

Arkansas panelists describe capital punishment as ‘legalized lynching’

What I learned working in a Texas prison: Retribution, not reformation | Analysis by Michael Chancellor