Charles Marsh knows something about evangelical anxiety. He grew up in the middle of it as the son of one of the most prominent pastors in the Southern Baptist Convention.

The SBC of Marsh’s childhood was the racially tinged Mississippi and Alabama of the 1960s. And the SBC of Marsh’s college years and young adulthood was a denomination at war with itself not over race but over the Bible. His father’s church, Second Ponce de Leon Baptist Church in Atlanta, played a reluctant role in this drama.

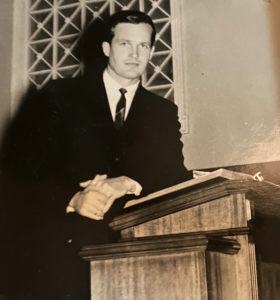

Robert Marsh in Dothan, Ala., where he led a Southern Baptist church to integrate.

The elder Marsh’s predecessor in the prestigious Atlanta pulpit had been Russell Dilday, who left there to become president of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas. He eventually was fired from that role by fundamentalist trustees put in power by the so-called “conservative resurgence” Dilday had predicted while still in Atlanta.

In 1976, Dilday warned his Atlanta congregation the convention’s attention should not “be wasted on differences in theological positions but rather spent on unity and usefulness in the task God has given us to carry out.”

In 1978 — one year before the “conservative resurgence” elected Adrian Rogers as the first in a string of SBC presidents who would change the course of the nation’s largest non-Catholic denomination — Dilday left Atlanta for Fort Worth. The next year, 1979, just as what some called “the controversy” kicked into full gear, Robert Marsh was called to succeed Dilday at Second Ponce.

Charles Marsh was 21 years old and a student at Gordon College, a private Christian school in Massachusetts. Nearly a decade later, Charles would be a fellow at the Baptist Theological Seminary in Ruschlikon, Switzerland — one of the high-profile targets of SBC fundamentalists seeking to clear all vestiges of “liberalism” from SBC support at home and abroad.

According to Baylor University professor Doug Weaver, writing for the Baptist History and Heritage Society, Robert Marsh was an “intense denominationalist and missions advocate.” It was only after the conservative movement claimed victory in the SBC after the 1990 annual meeting in New Orleans that Marsh spoke to his congregation in a personal way about the denominational warfare.

Second Ponce de Leon Baptist Church

In an address to the deacons of Second Ponce, “Marsh argued that the basic problem was not fundamentalism versus liberalism, or conservative versus moderate. The issue was ‘a narrow-minded provincialism — a bucolic and narrow thinking — a mean spirit refusing to allow open discussion in search for truth.’ He agreed with the moderate stance that the conservative agenda has a ‘tragic litmus test’: ‘Who believes the word of God the way I believe the word of God?’”

Weaver explained: “Marsh’s address to the deacons was intensely personal. He lamented the toll the conflict had inflicted on his family, especially upon his brother-in-law, Fisher Humphreys, who had been criticized while teaching at New Orleans Seminary. Marsh also noted that his son, Charles, would most likely never have the opportunity to teach in a Southern Baptist school because he received his theological education at schools that would not affirm the SBC’s conservative direction.”

Indeed, the younger Marsh had gone on to complete master’s degrees and a Ph.D. through studies at Harvard Divinity School, the University of Virginia, the Free University of Amsterdam, and the University of Iowa.

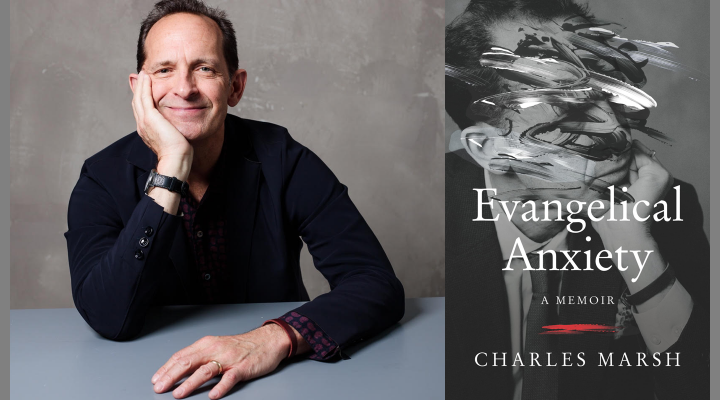

Fast forward three decades, and Charles Marsh now is a professor of religious studies at the University of Virginia and director of The Project on Lived Theology there. He’s also the author of eight books, including God’s Long Summer: Stories of Faith and Civil Rights, which won the 1998 Grawemeyer Award in Religion. He received a Guggenheim fellowship in 2009 and the 2010 Ellen Maria Gorrissen Berlin Prize fellowship at the American Academy in Berlin.

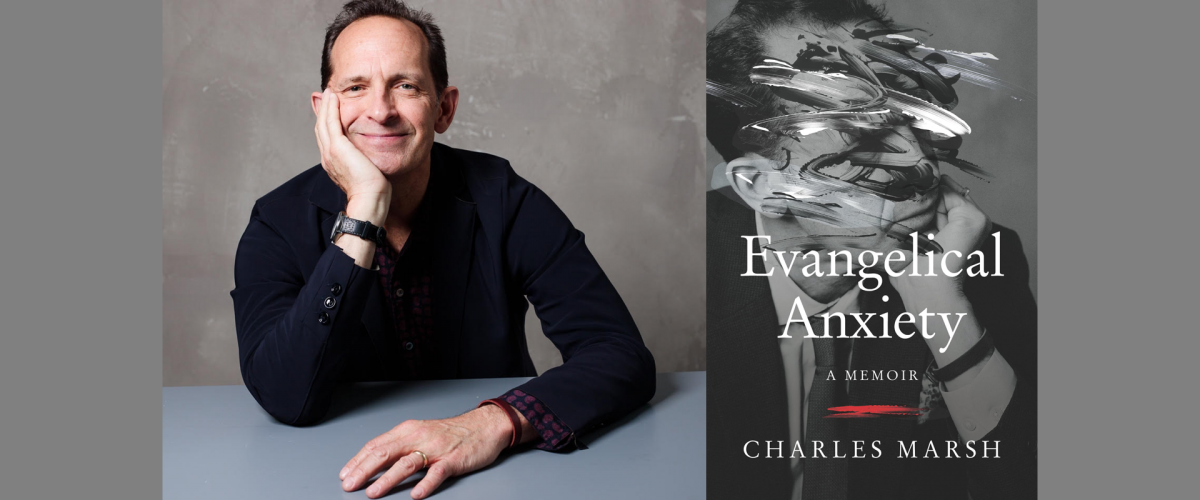

His latest book returns to the story of his life and the story that has played out around his entire life. Its apt title: Evangelical Anxiety.

Publicity for the book describes it this way: “In this riveting spiritual memoir, the writer, scholar and commentator tells the story of his struggles with mental illness, explores the void between the Christian faith and scientific treatment, and forges a path toward reconciling these divergent worlds.”

Marsh suffered with panic attacks and debilitating anxiety for years. Yet his Southern Baptist upbringing had taught him to trust in the power of God and to resist conventional therapy. Eventually, the professor broke with his upbringing, sought medical treatment and underwent years of psychoanalysis.

“He examines the tensions between faith and science and reflects on how his own experiences offer hope for bridging the gap between the two.”

The new book “tells the story of his struggle to find peace and the dramatic, inspiring transformation that redefined his life and his faith,” the publicity claims. “He examines the tensions between faith and science and reflects on how his own experiences offer hope for bridging the gap between the two.”

In a recent interview with Baptist News Global, Marsh said by the time he was ready to go off to college, he was more than ready to go.

“I certainly can remember the moment I said, ‘Enough of the white evangelical conservative South. I have got to get the hell out of Alabama and never come back. I grew up in Alabama and Mississippi. My parents moved to Atlanta when I was a freshman in college. So I never really lived in Atlanta but there was a time when I felt so incredibly suffocated by the narrow-mindedness of that subculture.”

“I just wanted the hell out of the South,” he continued. “It was not only about the sense of impoverishment that I was feeling with growing up in a very white middle-class evangelical culture, but it was also kind of the whole regional and cultural confinement I felt.”

Today, the professor of religion describes himself as “Christian but not religious.”

That’s a label that also fits many of his students, he said.

“They have no interest at all in evangelicalism, which has become known for intolerance and nationalism along with being dogmatic. These are students who may be deeply grounded in Scripture and in community. Some go to church, some have small groups, but whatever emerges out of their faith and practice will not be called evangelical by them.”

“They have no interest at all in evangelicalism, which has become known for intolerance and nationalism along with being dogmatic.”

The classroom isn’t his only connection to students who might identify as “Christian but not religious.” His wife, Karen Wright Marsh, serves as executive director of Theological Horizons, a campus ministry at UVA.

“Christian students of this generation do not have the same hang-ups with sexual identity and sexual orientation,” Charles Marsh said. Within Theological Horizons, “there are 20 or 30 students in the organization who would call themselves some letter in the LGBT spectrum who are also deeply committed to following Jesus.”

Evangelical anxiety has shaped his life and career from childhood to the present.

“I have a lot of friends who would have been loosely affiliated with some kind of evangelicalism 10 years ago and were just like, ‘I’m done,’” he explained.

“Thinking back to when I was a part of this culture, we knew many of these truths we promoted with such absolute certainty were really shaky. The Supreme Court is controlled by six conservative Christians, and yet somehow we’re still supposed to believe that as evangelicals and as conservative Christians in this country we’re constantly being persecuted.”

The antidote to the increasing isolation of evangelicals in America is to become open to differences, he said. “When a group encounters someone who is different in terms of sexual orientation or an immigrant or someone who is different, who represents a different worldview than their own, the first impulse shouldn’t be to obliterate that difference.”

“It’s time for us to really roll up our sleeves and try to make sense of what emotional and psychological purposes are being fulfilled in the way these men and women … use their faith as a weapon.”

And as someone who has walked the difficult road of unraveling the unhealthy messages of a narrow-minded faith, Marsh sees one other reason for evangelical anxiety: “It’s time for us to really roll up our sleeves and try to make sense of what emotional and psychological purposes are being fulfilled in the way these men and women think about God and how they use their faith as a weapon.”

The new book has drawn lavish praise from academics and pastors alike.

“This is a bold, beautiful memoir, at once transgressive and faithful. Marsh embodies a theology with the courage to tackle the taboo, including depression and desire, in prose that is evocative and seductive. In the end, we learn that the most astounding grace is found in the God we can tell our secrets,” according to James K.A. Smith of Calvin University and editor in chief of Image magazine.

A Rolling Stone magazine review opined: “An erudite glimpse into the psychology of white evangelicalism and how the current proliferation of white Christian nationalism could spring from the religious imperatives Marsh details.”

Ralph Eubanks, author of A Place Like Mississippi, summarized: “Marsh challenges the church to reckon with the mental health of the faithful, to be more open and accepting of how many of us struggle. Through gripping and honest storytelling, Marsh reveals the ways in which therapy can be a form of prayer.”

That’s not likely the kind of prayer Marsh learned in his father’s preaching growing up, but neither is this the same religious landscape of the mid- to late-20th century.