Some of the most enduring lessons of life emanate from our parents. As a child who was born and grew up in Jos, in the northern part of Nigeria, one of my childhood memories was the annual visit with my family members to my hometown in Anioma part of the then Bendel State during Yuletide.

As I would learn when I grew older, the visits every December were my dad’s own way of ensuring we didn’t lose touch with our root. The ritual happened up until I left to live with my newly married elder sister, Tina, in the eastern part of the country in the mid-1980s.

We usually arrived in my hometown ahead of Christmas in the car owned by our eldest brother, Victor. In his absence, one of our town members in Jos assumed the driving role.

Those were the wonder years of Nigeria, where road trips, as tiring and endless as the journey appeared then — it took about 10 hours or so — were still pleasurable. I do not remember us encountering any armed robbers on the highways, and “terrorist” or “terrorism” were not words associated with Nigeria. There was no worry of Boko Haram or any of its splinter groups as we know it today posing a danger to travelers in the northern part of the country.

Those were the wonder years of Nigeria, where road trips, as tiring and endless as the journey appeared then — it took about 10 hours or so — were still pleasurable. I do not remember us encountering any armed robbers on the highways, and “terrorist” or “terrorism” were not words associated with Nigeria. There was no worry of Boko Haram or any of its splinter groups as we know it today posing a danger to travelers in the northern part of the country.

Someone described Christmas season as a time of wonder and delight, a time to remember loved ones, and this was true for me and my siblings. Once we arrived my hometown, we would head for my maternal grandmother’s house in a different village within the community. There, we had the best of delicacies and farm produce. We often slept there too.

Unlike my parents, my grandmother, whom we called Nne, was not a Christian. She never took us to church but instead would wake us early in the morning for prayers to her gods. Apart from me and my siblings, there were also Onuwa and Ifeanyi, my cousins who lived with her. The prayers were marked by good wishes and success for her children and grandchildren and also against her enemies.

Prior to one such trip to my hometown, my immediate eldest sister, Josephine, passed away and during my grandmother’s supplication she agonized over the loss of her grandchild and prayed anyone responsible for her death would be paid back in the same coin. My only memory of Josephine today was when I visited her at the hospital in Jos, after she took ill. On sighting me, she struggled to call my name. Not long after that visit, we heard she had passed away. It broke my parents’ hearts.

On some days during those Christmas visits to my hometown, my siblings and I would help my grandmother or her surviving eldest son, uncle Matty, at the farm, far into the forest.

Three decades after my grandmother passed away, Onuwa, in reply to a question I asked her, said this of Nne: “She believed in God but never ever stepped into church. Some thought people in her generation believed God was too mighty and very far away and needed to be approached through some demi-gods.”

Beyond visits to my grandmother’s house, Christmas itself was marked with fanfare and festivity in my hometown. As children, we looked forward to receiving Christmas gifts from family members or older family friends and many houses within this Christian community and beyond had food and drinks to offer visitors. The merriment during the Christmas and New Year seasons wasn’t restricted to food and drink. Masquerades of different shades were a common sight across not just my community but different parts of the region, adding a touch of tradition and color.

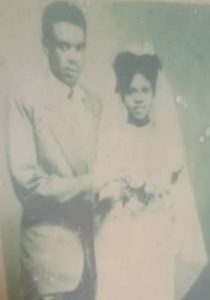

In my father’s house, Christmas typically began with a church visit. My father, Stephen Ezenweani Akaeze, was the first in the family to head for church. It’s a habit he was known for in Jos or wherever he resided, up until his passing in 2012 in my hometown. A staunch Catholic, my father attended church service every day starting with the first mass and ending with the evening service. On Sundays, he attended all the masses starting with the first.

The weather in Jos was mostly cold all year round, but this never stopped my dad from waking up early each day to take his hot shower and head for church. In my book The Newswatch Crisis and the Agony of the Nigerian Media Worker, I point out that my father set a record in church attendance — at least in my extended family. I’m his opposite as, at the time I wrote that, I barely attended church. My attendance rate may be better today, but it’s still typically a weekly, fortnightly or monthly thing, not a daily activity.

“One of my distant cousins once jocularly told me I didn’t need to pray as my father had done all the prayers on my behalf.”

Referring to my father’s church reputation, one of my distant cousins once jocularly told me I didn’t need to pray as my father had done all the prayers on my behalf. I had laughed at this, but in truth, there were times when, assailed by good fortune, I felt my father’s prayers, rather than mine, made them possible.

But the Christmas lesson my father tried to impart to his children didn’t completely sink in me. This is because, as an adult, I have no close affinity to my hometown.

Or the low affinity could simply be my own way of choosing, if I could, to lie low and operate from the background.

Over the years, as I grew into adulthood and lived on my own, Christmas came to hold little attraction for me. I wouldn’t travel from Abuja or Lagos to my hometown or any other Nigerian town or community just to celebrate it. I celebrate Christmas wherever I reside or find myself on that occasion, quietly, without fanfare.

In a recent piece I did on my mum, Regina, I forgot to mention something conspicuous about her: her prayers for me each time I visited my hometown or communicated with her via phone. It’s the one constant thing about her. So back in the day, whenever I arrived my hometown and knowing I would soon be on my way to my sister’s place, my mum would soon be urging dad to conclude his talk and pray for me. She allowed dad to pray whenever he was around; otherwise, she took charge herself.

I have her recent message this December — thanks to technology that enables instant communication across boundaries — praying for favor upon my life.

In decades past, it didn’t cost a fortune to celebrate Christmas and New Year in Nigeria. It’s a completely different situation today — evidence of how far things have deteriorated. Faced with the worst cost of living crisis in Nigeria currently, not a few families, including many Nigerians in the Diaspora feel the heat.

And so, I wonder: Unlike in the past, how many families can afford to have a good Christmas and New Year celebration today?

Anthony Akaeze is a Nigerian-born journalist living in Houston.