The church can be a healing resource for Native Americans whose cultures and ways of life are typically misunderstood if not outright ignored in the U.S. and Canada, activist Mariah Humphries said during a webinar hosted by Fellowship Southwest.

Indigenous societies understand the role of spiritual, emotional and physical balance in maintaining the holistic well-being of communities and individuals, she said. But Christians could help bridge the gulf between Native and Western worldviews.

“One of the opportunities the church has is we usually see someone as a whole person, and we try to take care of that total person. And instead of just saying, ‘This is your one sin,’ or ‘This is the one area you need to work on,’ we think of them corporately,” said Humphries, a Native American Christian who serves as director of the Center for Formation Justice and Peace and as a Native justice consultant to Fellowship Southwest.

The Nov. 11 webinar was presented to commemorate National Native American Day, to provide an update on key issues facing indigenous Americans and offer historical and cultural perspective to those reeling from the outcome of the presidential election, said Cameron Mason Vickrey, director of communications and development for Fellowship Southwest.

“Based on the election results, the work that she’s doing at this organization is going to be really critical for all of us, for healing and for helping us find a way forward,” Vickrey said.

With prompts from Vickrey, Humphries touched on issues including the state of Native ancestral lands, federal legislation intended to protect indigenous women and children from various forms of exploitation and President Joe Biden’s recent apology to Native people on behalf of the nation.

Land acknowledgments are “the low-hanging fruit” of land justice approaches for Native communities because they are largely symbolic, said Humphries, a citizen of the Muscogee Nation.

The process involves institutions issuing statements recognizing their land holdings originally inhabited by indigenous people. Many participants are institutions of higher education, including Brown, Indiana and Colorado State universities.

“We would like to acknowledge that we are meeting on the indigenous lands of Turtle Island, the ancestral name for what now is called North America,” the University of Texas explained.

A statement by Florida State University acknowledges its campuses are located on Seminole Tribal lands: “The university honors its unique and collaborative friendship with the Seminole Tribe of Florida, together paying tribute to the tribe’s great history and rich culture. We encourage all to learn about the significance of indigenous peoples in this region and throughout the nation.”

Land acknowledgments are “the low-hanging fruit” of land justice approaches.

While the acknowledgments are “a big deal when people actually start doing them” and they function mainly to uplift the institutions, “there is no investment in Native communities, no investment in having a Native voice come and try to impact the campus,” Humphries said.

The next step beyond acknowledgments is the Land Back Movement, which embodies the desire and drive to have traditional lands returned to tribal nations.

“But there could also be figurative messages with historical meaning,” she said. “We are seeing a lot of historical markers being renamed, and also park names. I think all of that is an honoring of land-back.”

Another iteration involves government agencies partnering with indigenous groups to help manage federal or state parklands, protect biodiversity and fight and prevent forest fires, she continued. “California’s done that. They started reaching out to local tribal nations to help with wildfires and to have controlled fires in the off season to help prepare for what seems to be inevitable in California.”

The effort to call attention to missing and murdered indigenous women also represents a form of protecting Native sovereignty, Humphries explained.

Women are often kidnapped, raped and disappear from reservations, often at the hands of white men working on pipeline projects on Native lands. “Law enforcement has not been great about reporting them as native women. They have reported them underneath other racialized identities or just as ‘unknown.’”

More than half of all Native women have experienced some form of violence, including physical assault, sexual assault, trafficking and homicide, Humphries reported. “They are seen as expendable, and their bodies historically have been rendered less valuable because they represent land, reproduction, indigenous kinship and governance — which is tribal sovereignty.”

The 2024 presidential campaign demonstrated just how salient some of these issues continue to be in American society, she added. “One of the biggest things we saw in this election was the protection of women, the identity of women, what we represent and just how our existence can stoke so much fear in some people.”

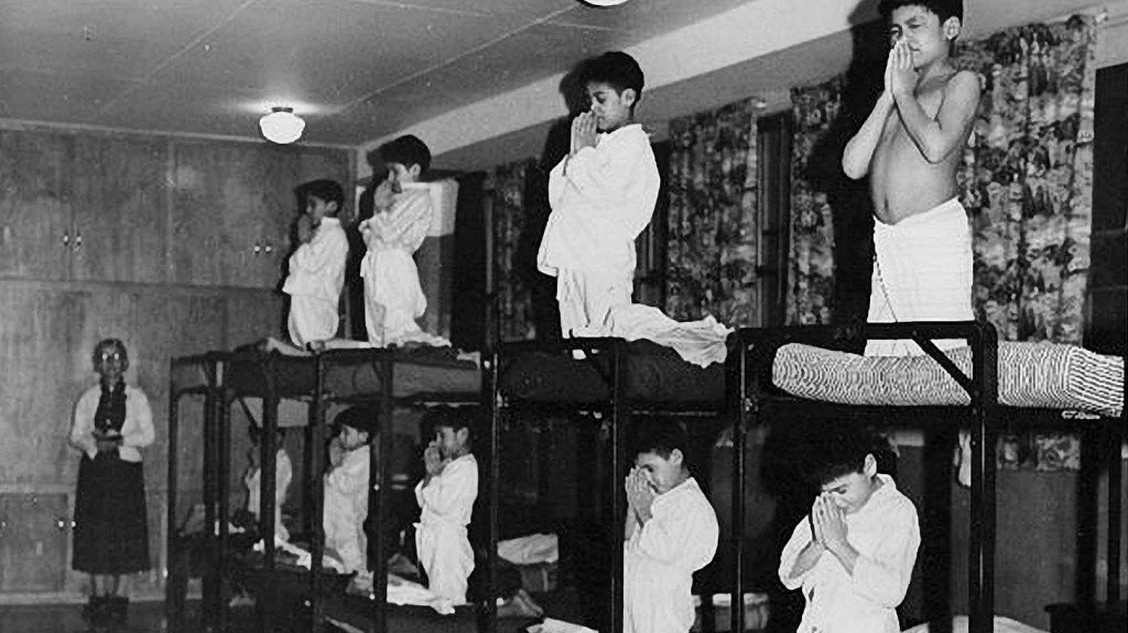

Tribal sovereignty also was assaulted by the U.S. boarding school program that attempted to assimilate Native children from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries, Humphries added.

“The motto was ‘Kill the Indian and Save the Man.’ The goal was to remove any aspect of nativeness in younger generations and full assimilation into a Eurocentric form of Christianity. Native children were removed from their families, their communities, their land. They were forced into this environment of abuse and separation.”

President Biden traveled to the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona Oct. 25 to offer an apology for the trauma Native people suffered at the hands of the government’s boarding schools where 900 children died.

“For indigenous peoples, they served as places of trauma and terror for more than 100 years,” Biden said. “Tens of thousands of indigenous children, as young as 4 years old, were taken from their families and communities and forced into boarding schools run by the U.S. government and religious institutions.”

The overture was needed and long overdue, but its timing was questionable, Humphries said. “The interesting thing about this apology was the timing of it. It happened two weeks before an election where it was a tense election, and it happened in a state where conveniently, in 2020, the Native American vote was widely promoted as significant in the election of President Biden. That is where some of the concern came.”

Related articles:

How churches can participate in the Indigenous Land Back movement and why they should | Analysis by Kristen Thomason

Columbus Day or Indigenous Peoples’ Day? The damaging Christian ‘Doctrine of Discovery’ at the heart of the American identity crisis | Opinion by Robert P. Jones

It’s past time to unearth and acknowledge our role in Native American boarding schools | Analysis by Laura Ellis