A few years back — 10 or 15 or so — a small church in Southern California noticed its big holiday productions were feeling a bit stale, especially to younger people.

“The old guard was putting on a show for the new people, but the new people were saying they really weren’t interested,” said Karl Vaters, lead pastor at Cornerstone Christian Fellowship in Orange County, Calif.

Nor were the “come-and-watch” events convincing visitors to return the following week — or at all, said Vaters, who pens a Christianity Today blog titled “Pivot: Innovative Leadership from a Small Church Perspective.”

And it dawned on the congregation that it didn’t stand a chance against Disneyland and megachurches like Saddleback, Mosaic and the original Calvary Chapel, all located just a few miles from the church.

So they quit doing the big shows and offered worship and a new sermon series on those special occasions, instead. Current and prospective members have responded well.

“That gave us more follow-up and follow through,” he said.

But Vaters and other experts told Baptist News Global that the changing religious and cultural currents that impacted Cornerstone Christian Fellowship have been decades long in the making and are presenting similar challenges to just about every church in the nation.

The proliferation of entertainment events at home and in communities is matched by the increase in family, professional and social obligations faced by churched and unchurched alike.

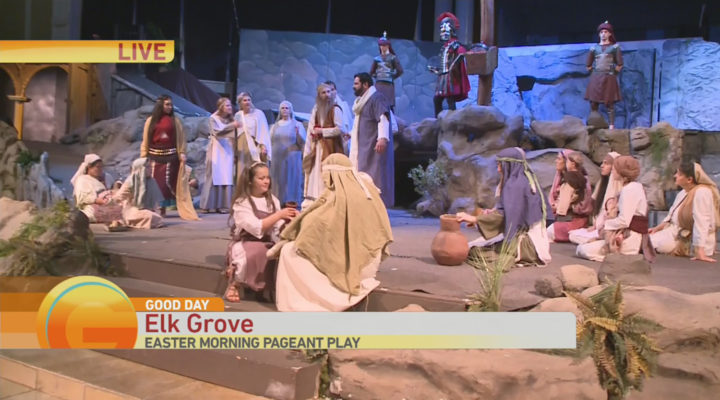

Few young people are interested in attending Christmas cantatas and large productions at Easter, experts say. (Photo/Emma Line/Creative Commons)

The resulting change in priorities, even among the most committed church goers, is leading churches to confront, or ignore, the postmodern culture in which institutional faith is taking a back seat to everything from Sunday soccer to web-based television and movies.

It means that Christmas cantatas and pull-out-the-stops passion plays, among other things, may need to go, experts say.

That’s pushing churches to find ways to remain relevant or risk extinction.

‘Expecting us to be incarnational’

There are plenty of churches flirting with the latter option, said Eddie Hammett, a congregational consultant and president of Transforming Solutions in North Carolina.

Many churches have yet to realize that the previous way of doing church and ministry — which aimed at attracting people to church campuses — doesn’t work in the present culture.

“The attractional age has passed us by a long time ago,” said Hammett. “But we’re still doing church trying to get people into our buildings.”

The era now can be described as one of engagement, which isn’t about facilities and programs, he said. It’s also a time in which churches must move from centralized to decentralized approaches to sharing the gospel.

“When you look at church websites and Facebook pages, it’s all about ‘ya’ll come,’” Hammett said. “But the Great Commission says ‘y’all go’ — and we still haven’t figured that out.”

And congregations continue to struggle with the new reality because five of the past generations have been steeped in — and dependent upon — the buildings-and-staff approach to operations.

“But in today’s post-modern and post-Christian culture, people aren’t coming as often,” he said.

The solution is to move beyond institutions and even beyond being missional to embracing the incarnational Christian life.

“It’s showing up in the environment, in the movie theaters or ballfields as church and as the body of Christ,” Hammett said. “The best illustration is that God sent his son in the form of Jesus.”

To do that, Christians must come to see where God is already at work in their communities, he said.

“The culture is expecting us to be incarnational,” Hammett added.

‘The sociology of Sunday’

What’s happening to the “come-and-watch” form of doing church has a strong precedent in the decline of revivalism in American Christianity, said Bill Leonard, professor of Baptist studies and church history at Wake Forest University School of Divinity.

Revivals dominated the religious and even entertainment landscape from as far back as the early 18th century through about the mid-20th century.

It was common at times to see revivals last from four to six weeks. In many cities and towns shops closed early and other public activities ceased for their duration, Leonard said. Evangelists could earn a living preaching revivals.

“Revivals succeeded because they were the best show in town,” he said.

But revivals began to decline as Americans began to have other options. As they did, revivals shortened in length gradually to just one, two or three nights.

“Movies were a big factor,” Leonard said.

Eventually the preaching of revivals could no longer sustain evangelists. And as revivals declined so did other events that were once staples, such as Christmas and Easter extravaganzas, Leonard said.

Today, the competition is even more intense for people’s time during Sunday mornings and on what used to be church nights.

Those include children’s soccer games and babysitting grandchildren, he said.

“I call it the sociology of Sunday,” Leonard said. “Even those committed to church engagement often cannot attend.”

“Sociology just caught up with the church,” he said.

‘It feels like a big risk’

Those factors were definitely at play when Vaters’ church dropped its holiday productions.

Vaters noted the definition of consistent church attender has changed over the years from three times a week to three times a month.

“There has been a major upheaval in the way people live their lives,” he said.

To reach out to people that are busy, Vaters suggested replacing big events with opportunities for action and service.

In a March 25 blog, Vaters said churches should find ways to get into the community to help, whether it’s painting and repairing dwellings, throwing a party for service men and women or cleaning a neighbor’s yard.

“When a person’s first exposure to our church is working with us to serve people, they get the idea that the church cares more about reaching out to others in Jesus’ name than being a passive audience,” Vaters wrote.

It’s also important to find ways to come together to give, such as preparing gift bags for impoverished children or tutoring.

“When unchurched people join us in giving to causes that don’t line the church’s pockets, they start trusting us a little more — and they’re open to trusting Jesus more, too,” he wrote.

Churches also should provide ways for people to have fun and to study scripture.

Changing directions like that can feel scary, Vaters told BNG.

“It feels like a big risk.”

But it’s worth it, he added.