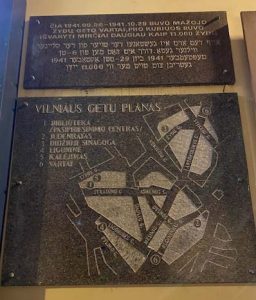

Historical marker, Vilna Jewish Ghetto

I spent the last weekend of October exploring the Old Town of Vilnius, Lithuania. I was in that grand 700-year-old city for speaking appearances and to visit friends. My dear wife, Jeanie, came with me.

Tuesday, Oct. 31, was free, and Jeanie and I decided on different itineraries. She went exploring in Lithuania’s many historic Catholic and Orthodox churches and some museums. I set out to explore where Vilnius’ Jewish community once had lived — and had been murdered during World War II.

It’s not hard to find. A place to start is to locate Zydu gatveė — “Jewish Street.” From my hotel, I headed south on Pilies then southwest a bit on Sv. Jono, where Vilnius University is located. I turned left on Gaono, named for the legendary Vilna Gaon, an 18th century Jewish scholar-rabbi-leader whose name, statue and reputation still linger in Vilnius. To get to his statue, I turned left on Žydų, encountering the statue on the right, near a workmanlike building that is apparently an art gallery, surrounded by a bit of green space.

David Gushee

You have to study the maps to know this is where the Great Synagogue of Vilna (now called Vilnius) once stood. Built in the 1630s, this was one of the grandest synagogues in all of Europe. It seated 5,000 people in a five-story complex. Two of the stories were underground because, it turns out, Christian rulers in Europe banned any synagogue from being built taller than a church. The Great Synagogue was looted, burned and partially destroyed by the Nazis when they occupied the city beginning in June 1941. Stalin finished the job when the USSR held power in Lithuania, leveling what remained of the synagogue and turning the space into a basketball court and a primary school. This was in the mid-1950s.

Wikipedia tells us in 2011 the current Lithuanian government announced plans to restore the synagogue. A news story I read projected that out to 2026 and promised not a synagogue restoration but a memorial garden and a Jewish community center. No sign of any of this was visible on my visit last week.

All scholars of Jewish history eventually learn about what happened in Vilna. Under the terms of the cynical pact between Hitler and Stalin in 1939, the Baltic region was included within the sphere of the USSR, which sent troops to Vilna in June 1940 and in August of that year annexed the whole of Lithuania into the Soviet Union — where it remained until the breakup of the USSR.

But Hitler broke this pact when he invaded the USSR on June 22, 1941. German troops were in Vilna by June 24. The city of 200,000, with an estimated 55,000 local Jews, together with perhaps as many as 15,000 Polish Jewish refugees, was now in the Nazi grip.

(Source: US Holocaust Memorial)

Scholars date the onset of the genocide campaign against the Jews of Europe not to 1939, when Hitler invaded Poland, but to June 1941, when he invaded the Soviet Union. While numerous Jews had been killed from the beginning of the war, the systematic mass slaughter of men, women and children in village after village, town after town, only commenced with the invasion of the USSR. This policy decision — the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” — was announced to a broader group of government leaders, and then organized across Europe, after the Wannsee Conference of January 1942.

The strategy undertaken by the Nazis in Vilna beginning in the summer of 1941 was to mix occasional massacres with ghettoization followed by more massacres. Nazi mobile killing squads, known as Einsatzgruppen, were the leaders in executing the destruction of Jewish communities across the East.

Ponary killing grounds

Eventually, the SS set up the now infamous killing centers, with their gas chambers and crematoria — Chelmno, Belzec, Treblinka, Majdanek, Sobibor and Auschwitz II-Birkenau. Before this, during the second half of 1941 in the larger Jewish population centers, the Nazis used a ghettoization strategy. Normally building on an already existing pattern in which many Jews lived in a Jewish quarter, the occupiers forced all Jews into crowded, impoverished ghettos as a part of the process that eventually would destroy these Jewish communities altogether.

In Vilna, the German strategy involved setting up two ghettos in early September 1941. Ghetto No. 1 was for those considered capable of work. Ghetto No. 2 was for everyone else. In just one month, the inhabitants of Ghetto No. 2, 40,000 people, had been murdered, mainly at a killing site 8 miles away called Ponary. The Jews in Ghetto No. 1, although subject to occasional massacres in the early months, survived until the final massacres in September 1943.

It is estimated that 75,000 Jews, mainly from Vilna, were murdered at Ponary.

So there I was, walking in the area of what had been for centuries one of Europe’s most storied Jewish communities, the “Jerusalem of Lithuania.” Home of the Vilna Gaon. Home of the Great Synagogue. Home of a vibrant religious and cultural life. Home of a community, 55,000 strong, fully one-fourth of the inhabitants of what is now the capital city of the proudly independent country of Lithuania.

“There were once 100 synagogues in Vilnius. Now there is this one.”

According to the Institute for Jewish Policy Research, the “core Jewish population” today in all Lithuania is 2,300. In Vilnius, there is one active synagogue, the Vilnius Choral Synagogue. According to the World Monuments Fund, which helped pay for the synagogue’s restoration, there were once 100 synagogues in Vilnius. Now there is this one. I walked by it. I found it locked up tight at midday.

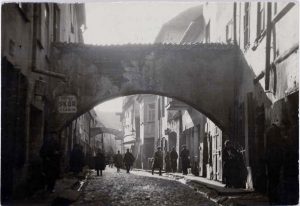

A cobblestoned street in the Jewish quarter, Vilna, 1930s. (Strashun Library of Vilna)

After that I moved further out of the main part of Old Town Vilnius to find the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum. There are two main sections. One features a permanent exhibition of the paintings of a Vilna Ghetto survivor named Samuel Bak. The other is a photography exhibit, apparently debuted in the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial, called “City of the Living, City of the Dead.” Striking photos juxtapose shots of the modern city of Warsaw with ghostly pictures from the Warsaw Ghetto. Specific people, who once lived in the Warsaw Ghetto, are superimposed on images of the vibrant modern-day city.

City of the Living, City of the Dead. Such an exhibit may have originated in Warsaw, but it travels well. Across Europe, Jewish communities that in 1933 contained 9.5 million people were destroyed, with only remnants surviving. Riga, Kiev, Minsk. Amsterdam, Rome, Paris. Vienna, Munich, Berlin. Lvov, Odessa, Lublin. Cracow, Belgrade, Budapest, Sarajevo. Athens, Bucharest, Sofia, Bratislava, Prague.

Even before visiting the old Jewish quarter in Vilnius, I felt the acute sense of Jewish absence in that grand old town. I asked my Christian scholar hosts about it and they told me, with sadness, they felt it too. I have felt that absence all over Europe.

“The Nazis and their local collaborators destroyed that civilization in less than four years.”

Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote in his Ethics that history has a cicatrix quality — history has scars, like people do. Europe was the primary site of Jewish civilization for many centuries. Jews were a diaspora community in Europe, often persecuted by their dominant Christian neighbors, but nonetheless builders of vibrant communities over centuries. The Nazis and their local collaborators destroyed that civilization in less than four years. Now both that civilization and its destruction mainly exist as scars, very faint ones at that.

Unless, perchance, you are Jewish. If you are a 75-year-old Jewish person, you were born just three years after the mass destruction of Jewish civilization and Jewish people in Europe. Today, Jews all around the world still remember the names of their murdered fathers and mothers, grandparents, sisters and brothers, husbands and wives.

Notice I have not used the abstraction “Holocaust” to describe the massive series of assaults on person after person, family after family, community after community, that occurred during World War II. By now this abstraction reduces real understanding of what occurred. “The Holocaust” sounds as if it is referring to one thing, one event. But it was the devouring of 6 million people, millions of families and hundreds of communities, day after bloody day.

Paintings by a Vilna Ghetto survivor named Samuel Bak

* * * *

What Hamas did to Israel on Oct. 7 ripped open this great scar in the collective Jewish psyche. By many accounts, it has been experienced as a wounding with greater gravity than any attack on Jewish people since World War II.

I read Israel’s massive, relentless, deadly military response in Gaza, currently estimated to have killed more than 10,000 people, as directly connected to this shattering re-traumatization, this plunging of a knife into a scar.

However much it may be couched in the clinical language of military strategy, Israel’s actions exude collective re-traumatized outrage. While a PTSD-type reaction is understandable, Israeli government and military leaders remain fully responsible for their actions in this current moment. The sacred value of human life, the obligation to make provision for humanitarian needs and safe refugee transit during war, and the requirement to honor such crucial wartime norms as noncombatant immunity always apply.

“The role of Christians in this current crisis is not to play end-times speculation games that pull us away from engaging real history and real choices in real time.”

The role of Christians in this current crisis is not to play end-times speculation games that pull us away from engaging real history and real choices in real time. It is not to bless everything our preferred side does. It is not to demonize any religious community or people. It is also not to forget the role Christians played in helping to create the historical context for the traumas those living between the Jordan and the Mediterranean continue to suffer.

It is to call all sides, and ourselves, to the infinite value of each human life, to mercy and love, and to the holy work of peacemaking.

This is what I was thinking as I walked the streets of Vilnius, city of the living, city of the dead, grieving and praying for those communities that today are shattered by war.

David P. Gushee is a leading Christian ethicist. serves as distinguished university professor of Christian Ethics at Mercer University, chair of Christian social ethics at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and senior research fellow at International Baptist Theological Study Centre. He is a past president of both the American Academy of Religion and the Society of Christian Ethics. His latest book is Introducing Christian Ethics. He’s also the author of Kingdom Ethics, After Evangelicalism, and Changing Our Mind: The Landmark Call for Inclusion of LGBTQ Christians. He and his wife, Jeanie, live in Atlanta. Learn more: davidpgushee.com or Facebook.