By Jeff Brumley

The prevailing wisdom is that there is little if anything new under the sun when it comes to politics and religion. But some ministers and expert observers are challenging that notion as the nation leans into the 2016 presidential election season.

Granted there are plenty of developments reminiscent of political seasons past, including conservative evangelicals lining up to preserve power while blacks and other minorities seek justice in the public square.

But there are some firsts, said Myles Duffy, vice president of Faith in Public Life, a Washington-based strategy group dedicated to promoting compassion and justice in the public square.

Duffy said he’s seeing an uptick among progressive faith groups, which may explain why Pope Francis’ messages on the poor and the environment are resonating with so many Americans, including Protestants.

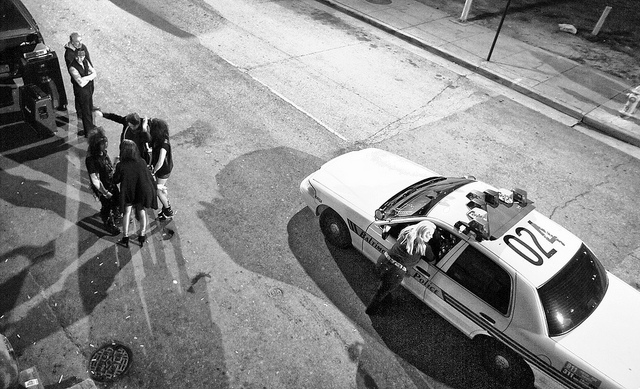

Repeated cases of police brutality are bringing together activists and churches in fresh ways while white conservative evangelicals are on the move again, motivated by high-profile Supreme Court rulings including the legalization of same-sex marriage.

And all of them seek to make their mark in some way on the outcome of the 2016 election season, according to Duffy.

“You see a lot of incredible things,” he said.

Churches play central role

He and other experts say those incredible things include recent high-profile cases of religiously infused politicking on local, state and national levels. While coming from across the political spectrum, they do have some common denominators.

“In my work, we do see a common thread of a wide array of clergy that are extremely active in the public sphere,” Duffy said.

A high-profile example of that occurred in July when hundreds of evangelical pastors gathered in Orlando for a training session on running for office.

It was billed as “a special training session on how to move from the pulpit to politics” and featured Southern Baptist and Republican presidential candidate Mike Huckabee as the keynote speaker, NPR reported.

The group was reminded of the sins of the nation, ranging from abortion and deficit spending to the Supreme Court’s recent ruling that legalized same-sex marriage. Participants were urged to start running for local offices in a bid to transform America into the godly nation it was founded to be.

Less publicized, but no less active, are progressive Christian ministers and lay people on the other end of the political and religious spectrum, Duffy said.

“I see some echoes of the civil rights movement in what I see around the country,” he said. In St. Louis County, Mo., where Ferguson is located, “churches are playing a central role in a lot of the activism” surrounding the Aug. 9, 2014, police killing of Michael Brown.

“There is a practical theology around movements like Black Lives Matter,” he said. “We are working with pastors in Cincinnati around the shooting of another unarmed black man.”

Politicians: ‘be mindful’

St. Louis-area resident Leah Gunning Francis has seen the development up close and personal.

Franics is the author of the newly released book Ferguson and Faith: Sparking Leadership and Awakening Community.

For it she interviewed two dozen area clergy from a variety of denominations, including Baptists. Each of the black, white, female and male ministers had been engaged in the protest movements in varying ways. They share how they see their work in terms of racial justice and expressions of faith.

Francis said she was also involved in the original Ferguson protests. It was because she had a direct interest.

“I am the mom of two young African-American sons and the wife of an African-American man,” said Francis, who is Methodist. “I was deeply disturbed by the numbers of black men and women who are finding themselves, unarmed, being killed by those who are charged to serve and protect.”

Reflecting on those days of a year ago, and on similar events that have occurred since, Francis said she expects movements like Black Lives Matter and I Can’t Breathe to have an impact on the 2016 election season.

Politically, that movement may not immediately reflect conservative white evangelical pastors running for office themselves, Francis said. But its grass-roots organization may likely be felt at the polls — locally and nationally.

“What I am hearing and seeing is more young people motivated to be engaged in the electoral process because we need to take seriously the importance in pushing and supporting candidates who support our agenda,” she said.

“There is not one voice or a face to this movement,” she said. “Its leadership is much more organic and from the marginalized spaces standing up and saying ‘I have a right to be heard.’”

And it was heard earlier this year in Ferguson, where voters turned out in record numbers to support black candidates in municipal elections, she said.

Huffington Post reported a wholesale change on the city council with the election of two black candidates.

That influence continues to be felt not only in street demonstrations but through behind-the-scenes coalitions working together for racial justice, against mass incarceration and on issues like Medicaid and health care expansion. What began as people coming together against police violence has blossomed into networks of citizens taking action around multiple issues, Francis said.

One sign of that cooperation came in January when a group of clergy and laypeople rallied at the Missouri statehouse and held a die-in to protest the death of Michael Brown and others at police hands, Francis said.

“It’s about coalition building and people are doing that,” Francis said. “I think politicians need to be mindful of that.”

‘Loss of cultural privilege’

In the historical sense, historian Bill Leonard said neither the conservative nor progressive and African-American political movements represent anything particularly new.

“Even since the colonial period in this country, clergy have engaged in politicizing and participating in public office,” said Leonard, professor of Baptist studies and church history at the Wake Forest University School of Divinity.

The gathering of conservative evangelicals in Orlando last month has occurred historically among African-American pastors to run for school board, county commission and even higher office.

It also mirrors the more recent history conservatives inspired by the late Baptist pastor Jerry Falwell and the Moral Majority movement to stack ballots with conservative candidates, he said. That in turn was part of a broader Reagan-era strategy to energize religious conservatives, especially Baptists, in the South.

Today, white conservative evangelicals, including Baptists like Huckabee, are re-energized with a greater sense of urgency and self-preservation, Leonard said.

“It is … another example of the concerns of conservative clergy about the loss of cultural privilege,” he said. “It is a recognition that evangelicals may have lagged in their commitments to voting and political engagement and may need to kick that up a notch.”

He said it’s also become clear to conservatives that “the culture is moving in other directions” and they are reacting by returning to politics.

Challenging office holders

White evangelical fear is having a clear impact on the 2016 election season, said Wendell Griffen, an Arkansas circuit judge and pastor of New Millennium Church, a Cooperative Baptist partner congregation in Little Rock.

“They are by and large imperialistic, capitalistic and legalistic people who are more interested in using the public sphere as a place for wielding oppressive power in the name of their faith,” Griffen said.

The Orlando pastors’ gathering, he added, is an example of an effort to turn Christians against Christians.

Which underscores another fact: it’s nothing new for Christians to run for political office, whether they are pastors or laypeople, liberals or conservatives.

“People elected as governors and presidents, judges and mayors have … almost always self-identified as Christians,” he said.

And that certainly includes African-Americans, who as minorities have struggled for social and political fairness by running for local, state and national offices, Griffen said.

“Participation in the process, first as voters then as candidates, has always been something that has been prized by people in the black tradition,” he said.

“Black people of faith have placed a value on that, but our social outlook, our public policy outlook, has often differed from that of the white evangelical,” he said.

Griffen said he expects movements like Black Lives Matter and I Can’t Breathe to be a force in a larger grass-roots movement to oust elected law enforcement officials, including prosecutors who have failed to hold police officers accountable in brutality cases.

“I think it will produce some activism to challenge current office holders and I hope it produces some candidates,” he said.

‘An incredible moment’

Whether or not it produces candidates, these disparate movements are producing some interesting unusual alliances in American politics, Duffy said.

Like the Center for American Progress, which promotes progressive values and policies, and the ultra-conservative Koch brothers working to address a broken criminal justice system. Democratic Senator Cory Booker and Republican Rand Paul introduced legislation to tackle the same issue.

But the rise of progressive traditions in politics is just as noteworthy, Duffy said.

There is also a church-led moral Monday movement in North Carolina and the ongoing work by Baptists to end payday lending and usury.

The Cooperative Baptist Fellowship has been among those calling for that reform.

“And I look at the immigration reform movement where you have evangelicals, Catholics and Baptists joining arms to work to protect families,” he said. “I think it’s an incredible moment we’re living through.”