From around the country 524 clergy responded to the call of North Dakota priest John Floberg to gather in support of the Sioux Nation’s attempts to stop construction of an encroaching oil pipeline near Standing Rock.

Floberg, leader of three Episcopal churches on the North Dakota side of Standing Rock, issued the call to show Christian unity with the Native American tribes he has worked among for 25 years.

“The Christian church has an obligation to support tribal nations when they are asserting treaty rights and to call upon governments to fulfill treaty obligations,” he said. “We can’t let any daylight be between us and people who are victims of racism. Racism has to be challenged in all of its forms.”

Baptist minister Ellin Jimmerson (right) and Ronya Galligo-Hoblit, a member of the Oglala Sioux nation. (Photo/Ellin Jimmerson)

Participants marched about a mile Nov. 3 from the main encampment of protestors and “water protectors” under the watchful eye of state police and pipeline security. On a hilltop they burned copies of the Doctrine of Discovery, a document that has been used to justify racism and enslavement of indigenous peoples since Pope Alexander VI wrote it in 1493.

This papal bull gave Christian explorers, especially those from Spain, the right to claim lands they “discovered” for their Christian monarchs. Any land discovered that was not inhabited by Christians could be exploited. If pagan inhabitants could not be converted, they could be enslaved or killed.

Native Americans have felt the sting of that papal edict since Europeans first landed in North America.

“The Doctrine of Discovery isn’t based upon the gospel,” Floberg said. “The gospel has Jesus coming among people and inviting relationship with them. The Christian gospel is one of liberating and not of oppressing. The gospel got connected to economic enterprise and it was distorted.”

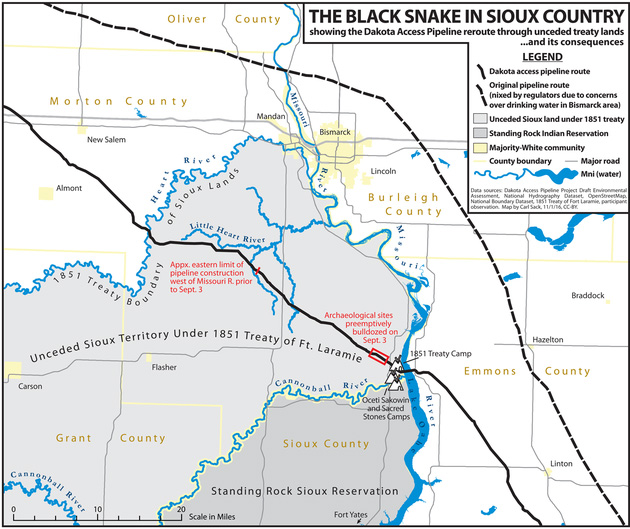

Floberg said the thousands of people who ebb and flow through the four main camps of protestors around the pipeline’s most forward point are not monolithic in their concerns. Some are more concerned about protecting the environment from potential oil spills; others don’t want another drop of oil drawn from the ground; others care most about broken treaties and maintaining Sioux Nation rights to protect native lands they never ceded in treaties to the U.S. government.

Unlike many Native American tribes that were confined to reservations, the Sioux signed treaties ending hostilities with the U.S. government in 1857 and 1868, but they remained on their own land. The pipeline construction is on Sioux land never ceded to the United States.

It has been under the control of North Dakota since 1889 when it achieved statehood. It contains sites the Sioux consider sacred and they claim Dakota Access, the pipeline builder, has violated several such sites, including burial sites.

“It’s pretty good that I’ve got 25 years here before I wade into these waters,” said Floberg, whose ministerial responsibilities have not changed, despite his additional work of ministering during this extended protest. After leading the clergy action he had a wake to attend, and a funeral to officiate the following day.

“I can see the benefit pretty strongly, having been here 25 years, to make a call of solidarity to stand with the tribe,” he said, “to hold a prayerful, peaceful, non-violent and lawful event right here where the pipeline is going through right now.”

“I can see the benefit pretty strongly, having been here 25 years, to make a call of solidarity to stand with the tribe,” he said, “to hold a prayerful, peaceful, non-violent and lawful event right here where the pipeline is going through right now.”

Christians can understand the value and significance of “sacred” things, even if they wouldn’t consider the same things sacred as do other cultures.

“Sacred is what’s held at the heart of a people having a history in a place,” Floberg said.

He said both “good things and calamities happened there.” Peace was arranged between tribes, floods took lives.

“When tragedy happens, Christians don’t run to that spot and say, ‘This is sacred, holy, joyful ground.’ We go to the spot and remember the loss that took place there and it becomes sacred.”

Ironic economy

A primary income source for the Standing Rock tribe is the casino they operate on their land. But its adjacent hotel has been filled for months with people coming to stand with the tribe. For the most part, they are not gamblers, so tribal income is down significantly.

Ronya Galligo-Hoblit, an Oglala Sioux, cries every day, according to her new friend Ellin Jimmerson, an Baptist community minister who responded to Floberg’s call for a unity event. Galligo-Hoblit says she cries in sadness for the situation that sees a “black snake” slithering through the plains, its belly potentially filled with oil.

She cries “out of pride” in seeing young people stepping into leadership roles as water protectors and guardians. And she cries for joy because of the support her tribe is receiving from around the nation.

Another Native American woman told Jimmerson, “I knew you [supporters] were coming. I’ve known you were coming for a long time.”

Jimmerson said her three days on site were “gratifying and disturbing.” She felt some of the younger persons were encouraging a more aggressive approach to their demonstration, including taking actions that would invite arrest.

Floberg told them he would not come to get them from jail if they got arrested. Authorities have been taking those they arrest to jails hours away by car from Standing Rock, and not offering return rides when they make bail. “If you have any notions of getting arrested, just tone it down,” he said during orientation Nov. 2.

Jimmerson said she did not witness any actions that prompted arrests. There were prayer circles around cars that had been burned out from previous activity.

To an outsider, the sprawling settlements look like war zone refugee camps. To Galligo-Hoblit they are beautiful because they represent tribal solidarity among the delegations that have come to support her people.

Jimmerson, who produced “The Second Cooler” documentary about the thousands who die crossing the barren Arizona and Texas deserts coming into America, said one of the strong elements of the Standing Rock story is the actions of solidarity being conducted by tribes all over the country.

Her own participation was to “show solidarity for the Standing Rock Sioux” who are but one indigenous people threatened by the power of corporations to “push them off their land.”

The ultimate goal, she said, is to “stop the pipeline and to regain control over their land.”

Floberg said protestors have the will to continue their protest through the bitterly harsh North Dakota winters. Although it has been unseasonably warm, locals told Jimmerson it is not uncommon to have three feet of snow on the ground by now.

Previous story:

Clergy from across U.S. to stand in solidarity with indigenous ‘water protectors’ at Standing Rock

Related commentary:

Confrontation at the Cannonball: The Dakota Access Pipeline controversy