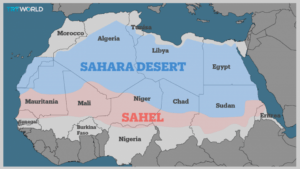

In Africa’s Sahel region — the current hotbed of terrorist violence — climate change has become a leading cause of worsening conditions.

Although Nigeria is not new to security challenges, some commentators in the country recently have linked the worrying crime statistics to foreigners who find their way into Nigeria through the Sahel region — encompassing Mali, Senegal, Mauritania, Chad, Burkina Faso, Niger, Cameroon — either to join ranks with the terrorist group Boko Haram or to engage in criminal activities.

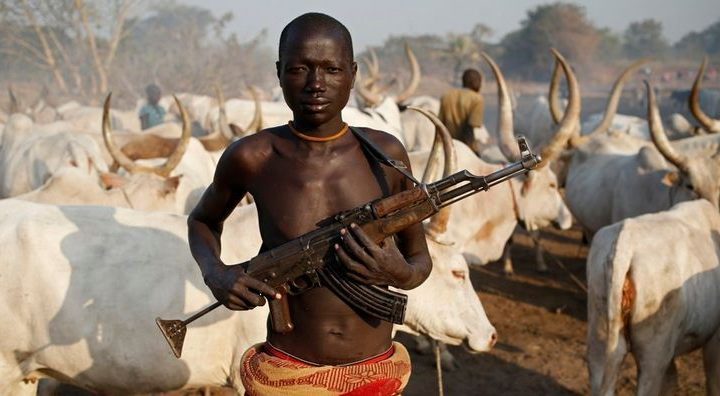

With climate change posing a threat to arid regions of the African continent, livestock farmers in search of grazing routes have, over the years, found their way into Nigeria via the country’s numerous unmanned border crossings. Some observers now believe that criminal elements and terrorists, posing as herdsmen, have infiltrated the ranks of Nigerian herdsmen traversing the country in search of grazing lands or have teamed up with terrorist groups like Boko Haram.

Map courtesy of TRTWorld.

Many of the itinerant herdsmen, armed with sophisticated weapons, are today scattered across forests in Nigeria with their animals, from where they are alleged to emerge to perpetrate havoc on citizens.

Economic incentives

There’s also an economic incentive to terrorism that is accelerated by climate change, according to William Assanvo, senior researcher with the Institute for Security Studies office for West Africa.

In a recent interview, he told BNG that research by his organization shows many who joined extremist groups in the region did so for economic reasons.

William Assanvo

“We conducted research questioning why people, particularly young people in Mali, join terrorist groups,” he said, explaining that a main factor identified was economics. “You can see people joining because they want to get money. You had people joining because they were not satisfied with their economic (situation). Some joined because they were unemployed and wanted something to provide them financial resources.”

Extremist groups are able to worm their way into the hearts of local residents by exploiting their socio-economic conditions, Assanvo said. “When they arrive in an area, they try to get a sense of the social and security dynamics and then they tend to exploit all the vulnerabilities in such areas. The vulnerabilities could be economic, social, political, security wise or in terms of governance. They exploit these vulnerabilities to recruit.”

Another motivating factor, he said, is the perceived need for protection.

“In that part of Mali, which is the northern part of Mali, there was no state representative, no security or military forces. The state was absent, so there was a level of insecurity as a result … that led some people in their quest for protection to join the terrorist groups because they believed they would be able to provide them some level of security.”

All road lead back to climate change

Underlying all that is climate change.

Tal Harris

Tal Harris, leader of the Climate Emergency Response project of Greenpeace Africa, explains that global warming plays a part in the crisis in a drought-prone part of a continent where many rely on agriculture for food and revenue.

“Drought, in particular, can lead to competition and violent struggles over resources such as water for livestock and for growing crops,” he said. “They can also exacerbate social conflicts between the haves and the have-nots. This is particularly alarming given that in some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Sahel region, in particular, 70% of the population relies on subsistence agriculture.

“Long-term drought in Nigeria has led to decertification and scarcity of land on which to grow crops and raise livestock. Farmers and herdsmen have been pushed to venture to new territories to find land for grazing or farming, often resulting in conflict.”

The scarcity caused by climate change has led to more violent clashes between herdsmen and farmers, he said. “In 2018, more than 2,000 people were killed. … Similar conflicts occur across other countries in the Sahel. Chad is one notable example of that. With science predicting more intense and irregular weather in the 21st century, such conflicts might grow.”

This is a recipe for a disaster, he explained: “Over-exploitation of natural resources coupled with climate change, specifically high temperatures, can increase the risk of violence,” and “tension and conflict are more likely with mass-migration of people, which can result from extreme events such as heatwaves, flooding or drought.”

“Over-exploitation of natural resources coupled with climate change, specifically high temperatures, can increase the risk of violence.”

The bottom line: “A peaceful future means a greener future.”

One way to reduce the risk of such deadly conflicts, Harris said, is for governments to declare a climate emergency and take climate action, as demanded by young Africans from countries such as Senegal, The Gambia, Kenya, South Africa and Nigeria.

“What these young Africans are rightly demanding is more investments in mitigating CO2 emissions, as well as in adaptation measures to the climate crisis,” he said. “This means better infrastructure and the restoration of ecosystems like forests and mangroves and protection of existing ones.”

A dangerous present reality

Meanwhile, in the present, it is difficult to keep tabs on the number of criminal activities linked to terrorists or armed herdsmen in Nigeria.

One day late last month, no fewer than 18 persons lost their lives after herdsmen reportedly attacked Egedegede, Obegu and Amuzu communities in Ishielu Local Government Area of Ebonyi State under the cover of darkness.

The attack happened days after eight members of the Redeemed Christian Church of God were kidnapped on a journey in Kaduna State, Northern Nigeria, and three weeks after 39 students of Federal College of Forestry Mechanisation, Afaka, Kaduna, were taken hostage by armed men who invaded their school.

While the Redeemed Church members later regained their freedom, only five of the students have yet been freed.

“West Africa’s Sahel region is headed for its deadliest year of Islamist-militant violence.”

“West Africa’s Sahel region is headed for its deadliest year of Islamist-militant violence,” wrote Katarina Hoije, Samuel Dodge and Jeremy Diamond in an April 3 report in Bloomberg. “Insurgents have killed at least 450 civilians in the region this year, … compared with 401 last year. The first three months of 2021 have seen more non-combatant deaths blamed on jihadist groups than the same period last year. … At least 1,000 people overall have died in attacks this year, including soldiers and militants.”

An appeal for Easter hope

The urgency of this situation made its way even into Easter sermons in the region.

In an Easter message, the Pentecostal Fellowship of Nigeria called on the administration of Muhammadu Buhari to do more to secure the lives of Nigerians but also appealed to those involved in criminal activities to turn a new leaf: “The Pentecostal Fellowship of Nigeria urges the different individuals and groups engaged in all forms of terrorist and violent activities to stop this wanton killing of Nigerians. We urge Boko Haram and other terrorist organizations to lay down their arms and table their grievances so that resolutions can be explored. We appeal to the bandits, herdsmen, kidnappers and the different elements to desist from their criminal activities and give peace a chance.”

Anthony Akaeze is a Nigerian native and religion journalist who currently lives in Houston and covers the African continent for BNG.

Related articles:

Boko Haram is still plaguing Nigeria claiming to do God’s work

Three years later, Leah Sharibu is still held captive, reportedly for refusing to renounce her faith

In Nigeria, the politics of religion and the search for peace are never-ending