New research is shedding light on a term — and a group of Americans — known as “spiritual but not religious.”

They prefer yoga and meditation to scripture and worship. They define God in individualistic ways and they almost always have negative views of organized religion — especially of Christianity.

And that’s the part that bugs Christians who have discovered, within their own tradition, contemplative practices that would appeal to the spiritual but not religious, if only churches would discover and promote their practice.

“A lot of people aren’t aware that this is part of Christian tradition and that’s because the Western church … just really forgot about a lot of that,” says Michael Sciretti Jr., a teacher with the Epiphany Institute of Spirituality, which works to connect Baptists with contemplative forms of Christianity.

New research by the Barna Group has uncovered just how far some of those seekers are from traditional faith, and yet how open many of them may be to conversations about Christian mystical practices.

Barna reported earlier this month that there are two distinct groups among those who identify themselves as spiritual without being religious.

One of the groups self-identifies as spiritual but with a religious faith that is no longer important to them. Among them, 37 percent are Christians, including 15 percent Catholic, 2 percent are Jewish and 2 percent are Buddhists. Another 1 percent are listed as “other.”

Barna said this group can be described as irreligious — meaning they define themselves as spiritual and do not consider their religious faith is unimportant to them.

“For instance, 93 percent haven’t been to a religious service in the past six months,” according to the April 6 report “Meet the ‘Spiritual but Not Religious.’”

Among them, 33 percent said they are unaffiliated while 20 percent are agnostic and 6 percent are atheists.

Among them, 33 percent said they are unaffiliated while 20 percent are agnostic and 6 percent are atheists.

A second group identified by Barna describes itself as spiritual without any religious identity at all. Nearly 60 percent of them are unaffiliated while 30 percent identified as agnostics and 12 percent as atheists.

But the differences between the two groups does not affect the practices and beliefs they have in common, Barna said.

“Even if you still affiliate with a religion, if you have discarded it as a central tenet of your life, it seems to hold little sway over your spiritual practices,” the survey found.

Barna noted that the “spiritual but not religious” demographic should not be confused with another group of Americans identified as those who “love Jesus but not the church.”

That group “still strongly identify with their faith,” the organization reported, “they just don’t attend church.”

‘Truth in all religions’

A commonality among those who see themselves as spiritual, though not religious, is a shared unorthodoxy in defining God. They are more likely to view God as “a state of higher consciousness that a person may reach” than as the omniscient creator of the universe, Barna said.

Those who identify as spiritual also are as likely to be polytheistic as they are monotheistic. The divergence in views about God is a welcomed state among those who identify primarily as spiritual.

“Valuing the freedom to define their own spirituality is what characterizes this segment,” Barna reported.

They are also generally ambivalent about faith, many of them seeing it as a source of harm in their lives and in society.

“Seeking autonomy from this kind of religious authority seems to be the central task of the ‘spiritual but not religious’ and very likely the reason for their religious suspicion.”

Another common denominator: They believe all religions teach the same truths.

“For them, there is truth in all religions, and they refuse to believe any single religion has a monopoly on ultimate reality,” Barna said.

Research shows that yoga is the top spiritual activity and expression of Americans who self identify as “spiritual but not religious.” (Photo/Evan Lovely/Creative Commons)

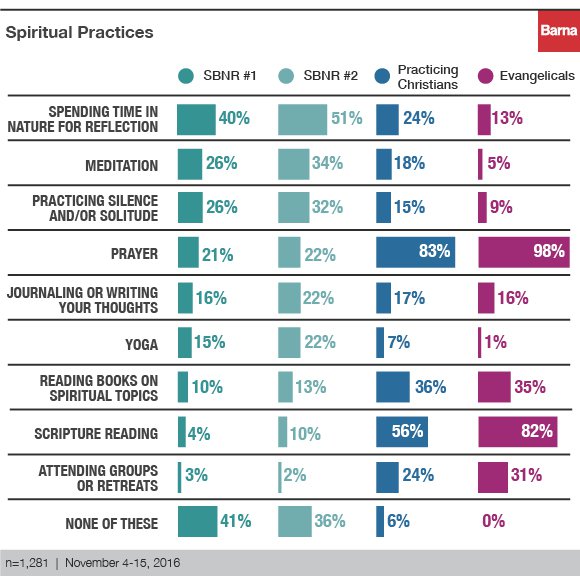

While they generally avoid reading scripture, prayer and group retreats, spiritual-but-not-religious adherents are more likely to engage in practices such as yoga, meditation, silence, solitude and other informal and individualistic activities.

Those who are spiritual, but not religious “represent people outside of church who have an internal leaning toward the spiritual side of life,” Roxanne Stone, Barna’s editor in chief, said in comments included in the report.

‘Becoming who you really are’

And that can be fertile ground for the church to build on, Sciretti said.

Often, those who say they are spiritual but not religious come from faith backgrounds that were overly rigid or even toxic. Most never learned there are an array of ancient Christian practices that would likely resonate with their present-day yearnings, he said.

Centering prayer and contemplative prayer are forms of Christian meditation that rely on silence. Lectio Divina uses scripture to focus the mind prayerfully and meditatively. The labyrinth focuses the mind through prayer and meditation.

Some Christian leaders say contemplative practices, such as centering prayer and the prayer labyrinth, offer the spiritual depth and mystery yearned for by those who consider themselves to be spiritual, but not religious. (Photo/Quester Mark/Creative Commons)

“There are other things like that that can be unearthed,” Sciretti said.

Churches must find ways to discover and present such contemplative practices. Doing so would connect with those currently pursuing faith outside of any religious context.

“It relates to how you reach people who are spiritual but not religious and who have only a particular understanding of what Christianity is — fundamentalist, legalistic, exclusive but not transformational,” Sciretti said. “But Christianity is about transformation and it’s about becoming who you really are.”