Cornell West may be the best-known Black academic and social activist in America, so his scathing resignation letter from Harvard Divinity School July 13 immediately went viral online.

His departure from Harvard to Union Theological Seminary highlights a national debate about academic tenure, race and politics that has been simmering for more than 60 years.

Nikole Hannah-Jones (Photo: John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation)

That simmering tempest reached a full boil this spring and summer, however, as the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill came under intense scrutiny for backtracking on a pledge to hire a Black female journalism professor to a tenured position. University administrators changed their mind about Nikole Hannah-Jones after a major donor to the journalism school objected to her hiring with the protections offered by tenure.

Facing enormous public backlash for their snubbing of Hannah-Jones, in part because of her work on the New York Times’ 1619 Project, UNC eventually relented and restored the offer for a position with tenure. But it was too late. Jones rejected the offer and took another job at the Howard University School of Communications, with tenure.

‘I’m too controversial’

West’s dramatic resignation from Harvard Divinity followed less than two weeks later. Yet Harvard Divinity is no bastion of conservative political ideology — the forces that conspired against Hannah-Jones. Even so, West blasted Harvard for falling into “decline and decay” fed by a “talented yet deferential faculty.”

His list of complaints included low pay, lack of promotion, lack of tenure, sidelining of his courses due to “the shadow of Jim Crow” and the university’s attitude against the Palestinians in their struggles with the modern state of Israel.

He told The Boycott Times there are “taboo issues” at Harvard and that one of them is “the Palestinian cause, wrestling with a serious moral spiritual political critique of the Israeli occupation.”

By his account, West’s outspoken views on this and other social and political issues made him too hot to handle even for Harvard. He told the Boston Globe: “What I’m told is it’s too risky. And these are quotes. It’s too fraught. And I’m too controversial.”

Although Harvard officials haven’t said much, they have explained that West’s shared position between the divinity school and the department of African American studies was not eligible for a tenure track. West’s allies say that’s an excuse that would have been mitigated for other faculty members.

Tenure in peril nationwide

A 2018 report by the American Association of University Professors sounded an alarm about the decline of tenure-track positions at colleges and universities. It found that three-fourths of faculty positions are non-tenurable positions.

Tenure is a way of guaranteeing certain professors job protection unless fired for cause or under extraordinary circumstances such as a financial crisis. It is rooted in a desire to promote academic freedom and freedom of speech.

“Over the past few decades, the tenure system in U.S. higher education has eroded.”

“Over the past few decades, the tenure system in U.S. higher education has eroded,” the AAUP report said, adding: “Tenure protects academic freedom by insulating faculty from the whims and biases of administrators, legislators and donors, and provides the security that enables faculty to speak truth to power and contribute to the common good through teaching, research and service activities.

The Chronicle of Higher Education recently updated the status of tenure in the U.S. with this report: “In 1993-94, more than half, or 56.2% of faculty members at institutions with a tenure system had tenure. By 2018-19, that number had fallen to 45.1%. These declines are driven in part by declines in the percentage of full-time faculty across the university. In 1970-71, almost 80% of faculty members were full-time. By 2018-19, that number was under 55%.”

Even within The Chronicle, academics are expressing varied views on the viability of tenure as a given. Some see it as essential to free inquiry, while others see it as outdated and cumbersome.

Inequities in race and gender underlie some of the critique. For example, only 36% of full-time faculty in American universities are women. And at schools that grant bachelor’s degrees, only 5.2% of tenured faculty are Black and 6.6% are Latino.

Colleges and universities

While UNC Chapel Hill ranks among the largest public universities, debate over tenure ripples down to even the smallest colleges and universities. And while state-funded schools face political interference from state legislators, governors and donors, private faith-based schools face similar political challenges wrapped up in theology.

While state-funded schools face political interference from state legislators, governors and donors, private faith-based schools face similar political challenges wrapped up in theology.

A case study in this challenge is Southwest Baptist University in Bolivar, Mo., where the political machinations of a state Baptist convention have threatened accreditation and caused turmoil among faculty.

The university now faces two separate inquiries related to denial of tenure. The first involves a claim by an alumnus, Russell Jackson, who believes attempts to remove religion professors and demands by the Missouri Baptist Convention for new governing documents meant “the school’s academic integrity is about to be irrevocably sacrificed by trustees who have conflicts of interest and are about to breach their fiduciary duty to the university,” according to Word&Way.

Dwayne Walker

University trustees had taken the unusual move of denying tenure or promotion to multiple professors even though those faculty members had been previously approved at all other levels. One of those denied tenure and terminated is Dwayne Walker, who was director of the bachelor of social work program.

Among other points, Walker said trustees used theological statements to justify his denial of tenure, even though the governing documents adding those requirements were not adopted until after he applied for tenure based on the existing standards.

That highlights a common threat facing faculty especially at Southern Baptist and other evangelical institutions, as conservative trustee boards have adopted more and more theological statements that faculty are expected to affirm, sometimes on an annual basis. At Southwest Baptist University, faculty are now required to affirm four separate doctrinal statements. The same is true at several Southern Baptist seminaries.

The seminary situation

The Association of Theological Schools is the standard accreditation agency and data keeper for seminaries and divinity schools in the U.S. Its most recent report on faculty tenure was published in 2015.

At that time, ATS reported that 61% of full-time faculty at its 3,727 member schools were tenured or on a tenure track. However, when part-time faculty were added to the overall picture, tenured or tenure-track faculty dropped to 30%.

John Haas

In a 2015 piece for Marginalia, a publication of the Los Angeles Review of Books, John H. Haas took up the topic of “Tenure and Confessional Institutions.” Haas is associate professor of history at Bethel College in Indiana, where he teaches U.S. history, specializing in American religious history.

In the United States, tenure as a concept arose around the turn of the last century “because of the need to protect the integrity of the academic vocation,” he wrote. “The threat at that time took the form of seemingly arbitrary hires and dismissals, with the latter generating most of the heat around the issue.”

And while it might appear counterintuitive that faith-based, or “confessional” institutions like seminaries would benefit from having tenured faculty, Haas makes a case that offering tenure protects not only faculty members but also the school itself.

“Administrations that care about the reputation of their schools welcome the contributions of academic peers in the evaluation process that leads to promotion or dismissal because it contributes to institutional integrity: it helps to ensure that an academic institution remains academic,” he explained.

And in collaboration with the American Association of University Professors, most colleges and universities and seminaries in America eventually adopted faculty staffing models that included tenure.

A seminary case study

However, having tenured faculty on board can make it difficult to turn an institution’s ideology rapidly, as was the case with the six Southern Baptist Convention seminaries amid the so-called “conservative resurgence” of the 1980 and 1990s.

Bill Leonard

Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky., became a case study in this in the 1990s, when SBC conservatives gained a supermajority on the seminary’s board and began demanding changes in the faculty. Amid that process, longtime President Roy Honeycutt retired, and the conservative trustees replaced him with someone of their choosing, Al Mohler.

What had happened at Southern Seminary during the rightward shift of the denomination was a cry from SBC conservatives to achieve “parity” on the seminary faculty — to balance out their desired kind of conservative evangelical viewpoint with existing faculty who were perceived to be more liberal. This also involved a denomination-wide dialogue through a blue-ribbon panel called the Peace Committee.

What actually happened at Southern Seminary instead of parity, with the consolidation of power, was a drive to staff the school almost entirely with like-minded professors. Those deemed too liberal — a classification that included self-described “biblical inerrantists” who also believed God might call a woman to serve as a pastor — were dismissed, run off or denied promotions.

Bill Leonard was one of the faculty members caught in the crossfire. Not only was he personally the target of some angry trustees, but he also served on a faculty committee that attempted to negotiate with trustees.

What actually happened at Southern Seminary instead of parity, with the consolidation of power, was a drive to staff the school almost entirely with like-minded professors.

“Tenure made it possible for us to slow the takeover and require the trustees to follow procedures that allowed existing faculty to secure places elsewhere and to ensure that the rules were followed,” he explained. “I was on a committee of faculty and trustees that confronted proposed trustee efforts to impose the Peace Committee findings as part of the requirements for hiring, promotion and tenure. Our challenge brought the threat of accreditation probation and slowed down the process.”

Faced with political challenges, non-tenured faculty could not afford to speak their minds and defend themselves and their colleagues, Leonard explained. “Tenured faculty were the only ones who could respond to the ideological changes demanded by the board of trustees. It slowed down the radical change in ways that gave existing faculty time to move on. Not to have it would have meant that even a mass firing was possible in 1990 and beyond.”

Leonard became an early departure from the seminary faculty, leaving in 1992 for Samford University, one year before Mohler (ironically, a Samford graduate) was named president at Southern and accelerated the faculty purge.

20 years later, another challenge

Those initial changes at Southern Seminary all happened with tenure policies still in place, which as Leonard noted, slowed the process of transforming the faculty.

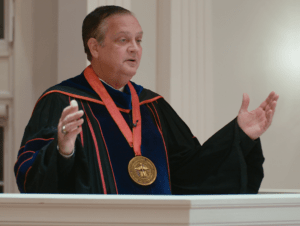

Seminary President Al Mohler

Then, 20 years after his arrival as president and sitting with a faculty largely of his own choosing, Mohler led seminary trustees to abandon tenure policies that had been in place for 60 years.

He explained at the time: “A tenure-based contract was the basis for hiring and retaining faculty from about 1960 to the present. But we have returned to making the election of faculty by the board of trustees the most important issue and returning faculty to teaching on the basis of a simple academic instructional contract.”

Mohler said tenure had become “a major impediment” to “academic quality” and created a “ticking fiscal time-bomb” that “every academic institution is going to have to abandon or face disaster.”

The financial component is a common complaint of seminary presidents and trustees, who see tenure as committing a school to retain faculty despite changing budget realities.

Haas believes such claims are likely overstated. In Kentucky, where Southern Seminary is located, for example, a Kentucky Court of Appeals in 2012 ruled that tenure cannot protect professors from dismissal when financial exigencies exist. That case involved Louisville Presbyterian Seminary. Other Baptist schools, including Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond, have dismissed tenured faculty when budget realities demand downsizing.

What’s more likely at play in opposition to tenure at confessional schools, Haas wrote, can be tied to “right-wing politics since at least the McCarthy era.”

What’s more likely at play in opposition to tenure at confessional schools, Haas wrote, can be tied to “right-wing politics since at least the McCarthy era.”

He quoted conservative evangelical essayist David French as expressing a “typical version of this attitude” by observing that tenured faculty “view themselves as a breed apart — entitled to lucrative lifetime employment no matter what they do.” French also had charged that tenure props up “vicious relics of the ’60s” who indoctrinate rather than educate, and who are “publicly spewing deranged invective” from within a cushy, consequence-free bubble.

One of the problems with ditching tenure, Haas suggested, is that it removes the ability of a school’s faculty to have meaningful input into hiring and promotion decisions and instead places authority heavily on a board of trustees, “who are rarely scholars in their own right.”

His main point is that such inevitably politicized decisions by trustee boards will invite unwanted publicity and scrutiny of a school.

“It is hard to imagine why a school would welcome that kind of attention — especially a religious school, given how often religious institutions are rent by ideological factions or compromised by apparent nepotism,” he said.

And indeed, that is the result currently playing out at Harvard Divinity School and at the University of North Carolina — lots of bad publicity.

Related articles:

If we don’t value our denominational colleges, do we value their faculty? | Analysis by Andrew Gardner

What should it cost a denomination to control governance of a university?