You know what I’m grateful for this year as Advent comes? A home.

Not just a roof over my head or a house with electricity and running water. I’m thankful for a national home, an imperfect but beloved country, a society that isn’t trying to starve me, kill me or force me out.

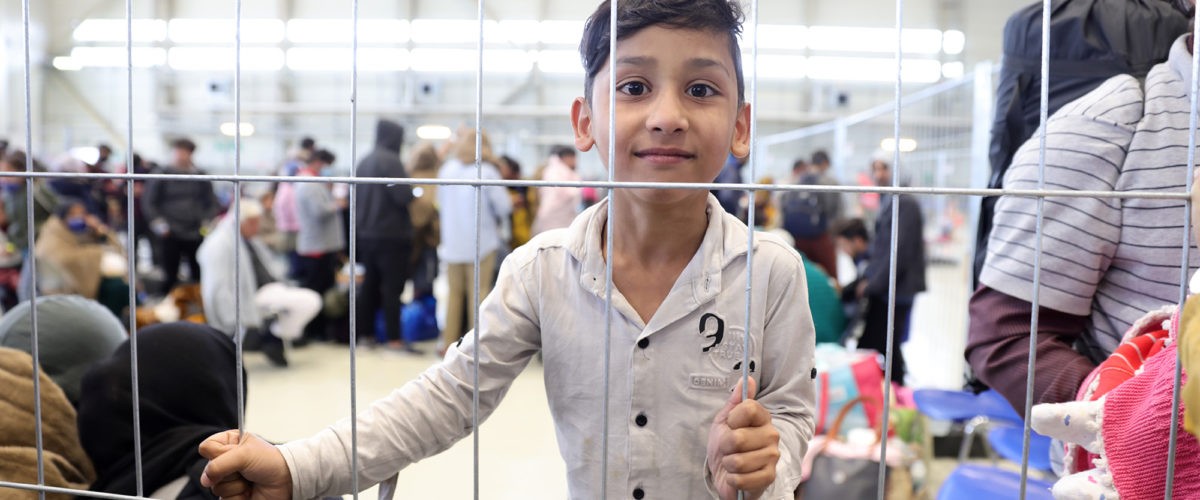

Tens of millions of refugees and migrants wandering the world wish they could say the same.

At the end of 2020, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees counted more than 82.4 million forcibly displaced people, driven from their homes by war or other forms of strife and instability. About 48 million remained internally displaced in their home countries, while more than 34 million had become international refugees, asylum seekers and others “displaced abroad.”

Erich Bridges

Nearly 70% of refugees forced from their home countries came from just five countries: Syria, Venezuela, Afghanistan, South Sudan and Myanmar (the 2021 American withdrawal and Taliban takeover in Afghanistan will drive refugee numbers from that country far higher).

That’s more than 1% of all humanity on the run, looking for a safe place to settle. Thirty-five million of them were children under age 18.

Not all, or even most, refugees seek to come to the United States. The top five national destinations of refugees in 2020 were Turkey, Colombia, Uganda, Pakistan and Germany.

Turkey was by far the top host country, with more than 4 million refugees and asylum seekers. The vast majority of them (3.6 million) were Syrians driven from the hellscape their country has become. But at least 300,000 Afghan refugees and immigrants live in Turkey, with more on the way (usually via Iran) after the Afghanistan debacle this year.

Thousands of Afghans driven from their homes by the Taliban takeover are seeking entry to Turkey. If they make it across Iran — a 1,400-mile trek through hostile territory — they’re meeting physical walls and aggressively unfriendly Turkish border police. Many are placed in holding facilities and eventually sent back into Iran.

“That’s more than 1% of all humanity on the run, looking for a safe place to settle. Thirty-five million of them were children under age 18.”

Turkey, struggling to accommodate millions of Syrians fleeing the civil war in their country, has declared it is unwilling to accept any more refugees or be a “refugee depot” for Europe. Many average Turks, coping with economic problems and job shortages, have become vocally anti-refugee. “Let them go elsewhere,” one Turkish shopkeeper told a Reuters reporter, referring to the new wave of Afghans. “We don’t care about them.”

What of the Afghans already in Turkey? Their status is tenuous at best. Many lack basic residence permits and live in fear of being stopped by Turkish police.

I visited Turkey recently and spent much of my time there talking to Afghan immigrants. Many of them work 12 hours a day, seven days a week for little pay, living with their families in slum neighborhoods.

“It’s day to day, one day and the next,” said “Farzad,” an Afghan Muslim who worries about the future for his wife and children. “We can’t live on this money. We have to go into debt.”

“Mukhtar,” orphaned by the Taliban as a child, became a follower of Christ after coming to Turkey several years ago. Now he ministers full time to other Afghans with the support of a Turkish church. But he has no illusions about his social status.

“I can serve here,” he told me. “But Turkey doesn’t want us here. They can deport us tomorrow if they want.”

“Hundreds of Afghan families are expected to be resettled over the coming year in my city alone.”

When I came home from Turkey, I attended a meeting hosted by my church to discuss the needs of the thousands of Afghan refugees resettling in the United States after our government’s abrupt abandonment of their country to the Taliban. Hundreds of Afghan families are expected to be resettled over the coming year in my city alone.

In short, they need everything — housing, medical aid, job training, driver training, school enrollment for their children, and most of all, English. Meanwhile, refugee resettlement agencies are struggling to rebuild after being decimated by the Trump administration’s anti-immigrant policies. Communities of faith must step up to meet the need.

“I’m going tonight to visit a family of seven staying at a hotel,” reported Zakir, a former Afghan refugee who now works to resettle other refugee families. “The mother just gave birth last night.”

I couldn’t help but think of Mary and Joseph, desperately searching for shelter and warmth as their holy child entered the world. Later, they fled as refugees to Egypt to escape death at the hands of Herod’s soldiers.

“Advent” means the coming, the arrival, of a special person or event. In the Christian calendar, it marks the coming of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. Could Jesus be coming to us again in the guise of an Afghan child? And if so, will we welcome him and give him shelter?

Erich Bridges, a Baptist journalist for more than 40 years, retired in 2016 as global correspondent for the Southern Baptist Convention’s International Mission Board. He lives in Richmond, Va.

Related articles:

Love ’em and leave ’em: America walks out on Afghanistan | Opinion by Erich Bridges

Buckle up: Global turbulence ahead | Analysis by Erich Bridges