By Bob Allen

The fate of a 60-year-old provision that allows churches to provide ministers with a tax-exempt “parsonage allowance” now lies in the hands of the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Chicago-based appellate court heard oral arguments Sept. 9 in a lawsuit filed by the Freedom From Religion Foundation claiming the IRS “confers a significant tax benefit upon religious clergy that is not available to non-clergy taxpayers.”

The Madison, Wis.,-based group that advocates for “freethinkers” including atheists, agnostics and skeptics claims the exemption is “patently unfair” and a violation of the constitutionally mandated separation of church and state.

The Madison, Wis.,-based group that advocates for “freethinkers” including atheists, agnostics and skeptics claims the exemption is “patently unfair” and a violation of the constitutionally mandated separation of church and state.

A legal brief filed in June noted that even the Bible commands citizens to “render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s.”

In November 2013 a federal judge agreed, ruling that a section of the tax code granting a benefit for “ministers of the gospel” not available to everyone else favors religion over non-religion, thus creating an establishment of religion prohibited by the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Numerous faith groups, including American Baptist Churches USA and the Southern Baptist Convention, filed briefs asking the appellate court to overturn that ruling and uphold the housing allowance based on a legal doctrine known as “convenience of the employer.”

Convenience of the employer is based on the premise that for something to qualify as income, there must be an economic gain that primarily benefits the taxpayer personally. Employees might enjoy things like meals, travel and office furnishings, for example, but if they are provided primarily to benefit their employer, they are not counted as taxable income.

The same principle applies to lodging. For jobs like hotel managers required to live on-site, government workers serving abroad or seamen who live aboard ships, lodging is a key component of their work.

An April friend-of-the-court brief by the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty argued that ministers are typically expected to live near the church they serve, and in smaller congregations they often function as the building’s primary caretaker.

Ministers are on call day and night and frequently expected to open their homes to church events, meetings with parishioners and out-of-town guests like visiting missionaries. Further, the brief stated, ministers often face frequent moves and limited choice, especially if they are poorly paid.

The IRS identifies a minister qualifying for the housing allowance as someone “duly ordained, commissioned or licensed by a religious body” with authority to “conduct religious worship, perform sacerdotal functions and administer ordinances or sacraments according to the prescribed tenets and practices of that church or denomination.”

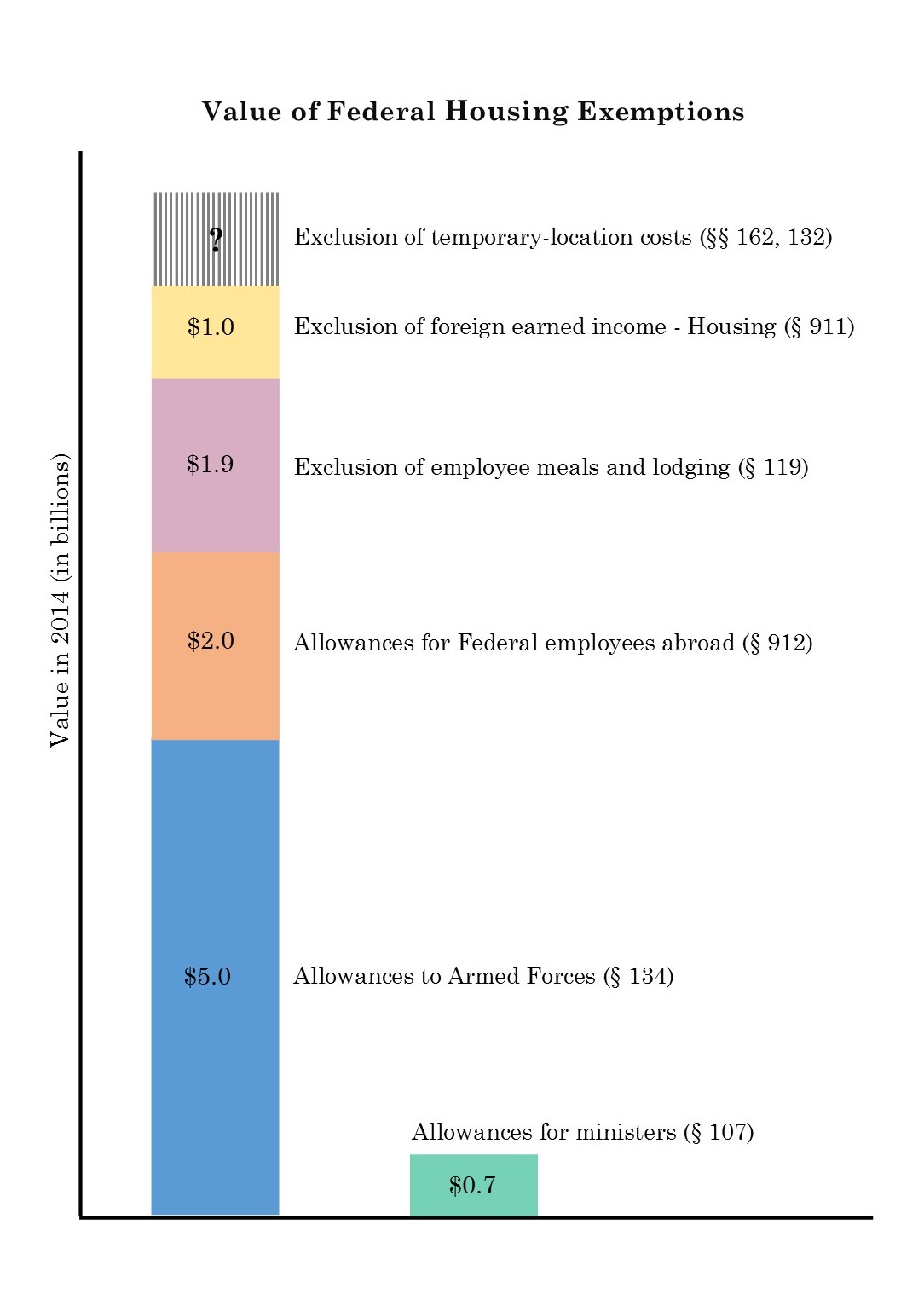

The Freedom From Religion Foundation argued that singling out clergy for preferential tax benefits violates the Establishment Clause. “Neutrality is a necessary requirement of the Establishment Clause, which means that tax benefits cannot be preferentially provided to support religion,” according to the brief. It further contended that the main motivation for keeping the allowance is financial self-interest.

“Questioning tax-free housing for ministers is controversial because it is valuable to clergy and churches,” the group argued. “From the perspective of financial self-interest, ministers and churches are understandably concerned, as the multiple amicus briefs attest, but not because of interference with religious beliefs.”

According to a Courthouse News Service report, much of the discussion at Tuesday’s hearing focused on standing. The plaintiffs aren’t asking for a tax exemption themselves, notes a case background page on the Becket Fund website. “Instead, they merely seek to eliminate the exemption for everyone else.”

The other decision the court must weigh is whether the benefit is constitutional. The Becket Fund brief maintained the tax code routinely provides special treatment to churches not to promote religion but to reduce entanglement between church and state.

Churches are exempt from Social Security and Medicare taxes for wages paid to ministers, for example. Instead, ministers are treated as self-employed. Churches and certain related entities do not have to file IRS Form 990, a statement of financial disclosure required of other nonprofits.

The Becket Fund claimed removing the parsonage allowance would increase church-state entanglement by putting the IRS in the position of determining which deductions claimed as business expenses qualify as ministry.

The brief also maintained the housing allowance reduces discrimination among religions by favoring groups like the Roman Catholic Church, which uses primarily church-owned parsonages, over other churches, where it makes more sense to reimburse the minister for living expenses than to purchase and maintain a parsonage.

Previous stories:

American Baptists defend clergy housing allowance

Diverse groups defend clergy tax break

Court strikes down clergy tax break