Semen est sanguis Christianorum. “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.”

Those words, attributed to the third century theologian Tertullian, appear in an Apologeticum written to defend against the many charges — cannibalism, incest, atheism, sedition, etc. — leveled at Christians, accusations often resulting in execution. The early Christian centuries were rife with martyrs who refused to worship state-sanctioned Roman gods, including the emperors.

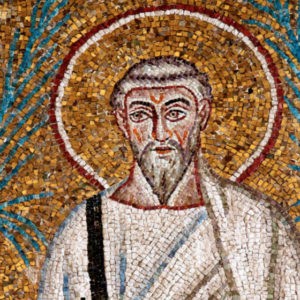

The Martyrdom of Polycarp (160 CE) details the earliest known account of post-biblical martyrdom, personified in the death of the bishop of Smyrna. It begins: “We write unto you, brethren, an account of what befell those that suffered martyrdom and especially the blessed Polycarp, who stayed the persecution, having as it were set his seal upon it by his martyrdom. For nearly all the foregoing events came to pass that the Lord might show us once more an example of martyrdom which is conformable to the Gospel.”

Mosaic of Polycarp

Of blessed Polycarp the document says: “For he lingered that he might be delivered up, even as the Lord did, to the end that we too might be imitators of him, not looking only to that which concerneth ourselves, but also to that which concerneth our neighbors … . Blessed therefore and noble are all the martyrdoms which have taken place according to the will of God.”

Sentenced to death in the “stadium” for refusing to confess “Caesar is Lord” or offer incense at the emperor’s shrine, Polycarp accepted that verdict as a public witness for Christ and the promise of eternity with him. The account of his dying remains a classic in the martyrology of the church.

Martyrdom defined

A martyr is “a person who voluntarily suffers death as the penalty of witnessing to and refusing to renounce a religion; a person who sacrifices something of great value and especially life itself for the sake of principle.”

What that “principle” might be remains a question of considerable debate, however.

Not all martyrs are as non-violent as Polycarp and the early Christians. Medieval “crusader/martyrs,” Christian and Muslim, were assured that death in battle against the “infidels” would bring eternal salvation. Today’s “suicide bombers” seek a similar martyrdom. Last month, when the California-based Church of Good Tidings honored Trump-pardoned General Michael Flynn with an AR-15 rifle, he responded with: “Maybe I’ll find somebody in Washington, D.C.” Huffington Post reported that “church members roared with laughter and clapped when Flynn suggested hunting humans in the nation’s capital,” behavior linking them all too closely with medieval crusaders, and a long way from Polycarp.

“Not all martyrs are as non-violent as Polycarp and the early Christians.”

Who is a martyr?

Consensus as to who is a martyr often depends on who does the dying and who interprets it.

Events in Charleston, S.C., in the 19th and 21st centuries illustrate that ceaseless dilemma. In June 1822, freedman Denmark Vesey was executed, along with numerous slaves, for allegedly planning an armed revolt against slaveholders.

That October, Richard Furman, pastor of Charleston’s First Baptist Church, described the plotters accordingly: “It is true, that a considerable number of those who were found guilty and executed laid claim to a religious character; yet several of these were grossly immoral, and, in general, they were members of an irregular body, which called itself the African Church, and had intimate connection and intercourse with a similar body of men in a Northern City, among whom the supposed right to emancipation is strenuously advocated.”

Yet in his 1901 treatise, Right on the Scaffold, the Martyrs of 1822, Quaker Archibald Grimke wrote of Vesey: “It is verily no light thing for the Negroes of the United States to have produced such a man, such a hero and martyr. It is certainly no light heritage, the knowledge that his brave blood flows in their veins. For history does not record, that any other of its long and shining line of heroes and martyrs, ever met death, anywhere on this globe, in a holier cause or a sublimer mood, than did this Spartan-like slave, more than three quarters of a century ago.”

In June 2015, 193 years after Vesey’s execution, Dylann Roof, a 21-year-old white supremacist, murdered nine worshipers at Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. The “Emanuel Nine” are venerated as martyrs, not because they chose death, but because they were faithful Christian witnesses against the murderous white supremacy of the shooter.

“The ‘Emanuel Nine’ are venerated as martyrs, not because they chose death, but because they were faithful Christian witnesses against the murderous white supremacy of the shooter.”

Yet when Roof, now sentenced to death for the murders, was asked by an arresting officer if he believed the massacre would have made him a martyr, replied: “Well, that would be nice, sure, but I didn’t know if that’s what would happen.” Two years later, a “Here & Now” radio broadcast asked: “Could Dylann Roof become a martyr for white supremacists?”

More recently, martyrdom was attributed to Ashli Babbitt, the 31-year-old woman shot by a Secret Service agent as she helped break through and attempted to enter the House Speaker’s Lobby at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6. That same day, a member of the Texas Oath Keepers and Three Percenters wrote on Facebook: “Trying to find the name of a woman that was gunned down by Capitol police today. She was unarmed and is the first Patriot Martyr in the Second American Revolution.”

To label Babbitt as either martyr or insurrectionist is to encounter divisions that produced the Jan. 6 Capitol events and remain unabated across the nation.

Anti-vaxx martyrs?

Is martyrdom an appropriate term for Americans who eschew COVID vaccinations, the largest percentage (24%) of whom are white evangelicals? Will they be considered martyrs for their adherence to certain principles related to faith and citizenship? Are they willing to die or infect others because of their specific religio-political perspectives? These include leaving their unvaccinated fate “in God’s hands”; resisting government policy as a form of religious freedom; insisting that vaccine mandates reflect a conspiracy of global control or that vaccinations facilitate a government-induced implant equivalent to “the mark of the Beast.” (I recently received a letter advocating that theory.) Will the term “martyr” ultimately be applied to those who resist vaccination, even unto death?

Guns and martyrs

And what of gun-related deaths? Should martyrdom be applied to such firearm-instilled murders at Columbine (1999), Living Church of God (2003), Virginia Tech (2007), Fort Hood (2009), Sandy Hook (2012), Mother Emanuel Church (2015), Pulse Nightclub (2016), Las Vegas Strip (2017), Tree of Life Synagogue (2018), El Paso Walmart (2019), Georgia Massage Parlors (2021)?

“In 21st century America, we are all potential martyrs, an implicit danger lurking in almost every imaginable communal setting.”

Some commentators resist that martyrdom designation since the individuals who died in these massacres did not choose to do so; their lives were taken from them. They are innocent victims of crazed individuals who wantonly used powerful firearms to send them to their deaths.

Others take a different approach. In a 2013 op-ed, University of Georgia professor Richard Zimdars wrote that after every mass shooting, an NRA representative should visit grieving families to explain “that their loved ones died as martyrs to the Second Amendment, that gun deaths are a necessary price for the right to purchase guns, and that this right is necessary for the pursuit of life, liberty and happiness for all Americans, even though it deprived their loved ones of their lives and pursuit of happiness.” He suggested that the NRA should “courageously propose a Second Amendment Martyr Remembrance Day.”

In a 2015 column, writer John Figliozzi declared that those killed in mass shootings “are all unwitting — and certainly unwilling — martyrs to a ‘cause’. … To be sure, they did not consciously volunteer for this particularly insidious form of martyrdom. But they truly were sacrificed — to the antediluvian cause of virtually unfettered firearms proliferation.”

Those two commentators echo a sobering reality: In 21st century America, we are all potential martyrs, an implicit danger lurking in almost every imaginable communal setting. As church and nation we are surrounded by too many martyrs. It is time to stop creating them. Past time, actually.

Bill Leonard

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

A millennial martyr? The complicated legacy of John Allen Chau

World religious leaders remember Shahbaz Bhatti as martyr 10 years later