Hands always have fascinated me, not only as an artist where we put something of ourselves in a new and visible form, but also as a manner of human connection. My interest might have begun long ago in kindergarten when we impressed our little hands into clay to make a traditional keepsake for our parents.

Then, in college, my curiosity was heightened when I saw cave dwellers’ handprints. I could almost feel their presence, looking at the art they made on rock walls around the world. I wondered, as many have, why fingers often were missing from the sprayed silhouettes, and even how they had materials to spray. It was impressive that without books or instruction of any kind, their drawings were so well-proportioned and realistic.

“My curiosity was heightened when I saw cave dwellers’ handprints.”

Despite the many questions raised, it’s agreed that cave art was a natural, creative expression, and a kind of ancient storytelling since some of the sites included writing. Much was recorded about cultures and common daily activities — hunting, dancing, family, birds, animals, weather, religious beliefs and death — in details that are quite astounding. I present a program about cave art at our local college, and it begins interesting conversations.

In the 15th century, hands were significant subjects in religious art. Two pieces are easily recognized; one is Michelangelo’s famous “Creation of Adam,” a fresco painted on the Sistine Chapel ceiling in Rome. God’s outstretched hand giving life to Adam, and to all mankind, conveys a promise of eternity. Being there in person years ago was an incredible moment of gratitude for me.

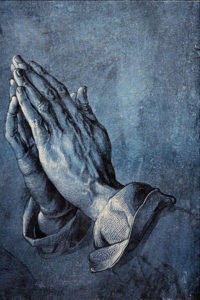

“Praying Hands,” Albrecht Durer

“Praying Hands” by Albrecht Durer (also Duerer) is a pen-and-ink drawing by the German painter, printmaker and theorist of the German Renaissance. These pieces, among others, still speak to the power of art’s endurance because they express our deeper search for meaning in life.

During the pandemic, hands took on a significant dimension. When handshaking was suspended, the world was advised, over and over, to “keep your distance,” “wash your hands,” and “use hand sanitizer.” At one point, it seemed that simple — if we’d just hunker down a bit, stay distanced and keep busy, life eventually would return to normal.

In the meantime, health care providers’ hands cared for the ill and dying, other hands wrote letters of love, and both men and women cooked and baked. Some hands made puzzles to pass the time, other hands served Communion and prayed; many, many hands sewed masks, and families painted messages on rocks to offer hope. Hands reached out as they could to other hands.

It’s our nature to serve God through touch, offering understanding and healing. Historically, in times of crisis, the arts speak for those most affected and help us all process fear, anger, truth and pain. Lately more artists (including those new to art) have become involved in social activism, protesting with signage for marches or creating public murals. They meet up with kindred spirits and contribute pieces to exhibitions, giving hands a new purpose: effecting change.

The activists’ art particularly reaches out to educate a world of “nice people” who often stay silent and comfortable in socially correct settings and in churches.

Silence (“peace”) is the complicity that ensures nothing changes.

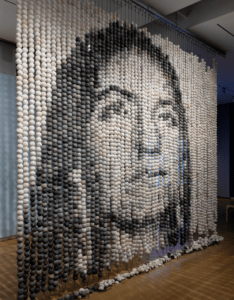

Sometimes these pieces are so stunning you just have to stop and learn more. We were in Santa Fe a few years ago at the Museum of International Folk Art and looked up to see a woman’s face in a suspended mosaic of beads. It was Cannupa Hanska Luger’s MMIWQT exhibit (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Queer and Trans People) — one handmade bead for every one of 4,000 missing or murdered women. I instinctively knew it was a creation about people by people for people, from hands.

Sometimes these pieces are so stunning you just have to stop and learn more. We were in Santa Fe a few years ago at the Museum of International Folk Art and looked up to see a woman’s face in a suspended mosaic of beads. It was Cannupa Hanska Luger’s MMIWQT exhibit (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Queer and Trans People) — one handmade bead for every one of 4,000 missing or murdered women. I instinctively knew it was a creation about people by people for people, from hands.

Luger launched an instructional video in 2018 seeking collaboration with communities across the United States and Canada to create and send 2-inch clay beads. He then fired, stained with ink, and strung the pieces together to create the sculpture. You can see a short video of the process here and read about the project here.

The “real” American Black history is gaining understanding and acceptance. Activists’ quilts tell their stories and are “historical documents,” says Carolyn Mazloomi, an artist, author and curator. Mazloomi was a 2014 recipient of a National Heritage Fellowship, specifically the Bess Lomax Hawes Award, bestowed by the National Endowment for the Arts. This is the United States government’s highest honor in the folk and traditional arts.

The Weisman Art Museum’s new presentation, “We Are the Story” with Mazloomi and Penny Mateer, explains: “When Minneapolis became the epicenter of the nationwide protest movement against police brutality and racism in America following the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, Textile Center and Women of Color Quilters Network (WCQN) joined forces.” This video is a non-threatening way to talk about tough subjects: race, political issues, church bombings and civil rights demonstrations.

Take a look at some exceptionally beautiful, vivid quilts by Bisa Butler, a very talented Black artist who explains her process for creating and how it relates to the Great Migration, voting rights, Black history, environmental leaders at the Smithsonian Art Museum.

Hands continue reaching out around the globe to make life better. You can make a difference.

When we extend our hands, it’s because we seek acceptance and peace. Or in the words of Mother Teresa: “If we have no peace, it is because we have forgotten that we belong to each other.”

Phawnda Moore is a Northern California artist and award-winning author of Lettering from A to Z. In living a creative life, she shares spiritual insights from traveling, gardening and cooking. Find her on Facebook at Calligraphy & Design by Phawnda and on Instagram at phawnda.moore.