W.A. Criswell was George W. Truett on the outside and J. Frank Norris on the inside, according to O.S. Hawkins, whose new biography of the legendary pastor of First Baptist Church of Dallas releases today.

Criswell grew up in the Texas Panhandle, where his father was a devotee of Norris, the fiery fundamentalist pastor of First Baptist Church of Fort Worth, and his mother was a devotee of Truett, the statesman pastor of First Baptist Church of Dallas.

Hawkins, who is among several successors to Criswell in the Dallas pastorate, wrote a previous book about the war between Truett and Norris that — perhaps coincidentally — sets up the story of Criswell’s life and times. The book is titled Criswell: His Life and Times.

Others have written biographies of Criswell but Hawkins brings to the endeavor hours of videotaped interviews with Criswell that were made decades ago on the condition that the contents not be released until 20 years after Criswell’s death. He died 22 years ago.

Others have written biographies of Criswell but Hawkins brings to the endeavor hours of videotaped interviews with Criswell that were made decades ago on the condition that the contents not be released until 20 years after Criswell’s death. He died 22 years ago.

Hawkins also brings to the work years of friendship with both the pastor and his wife, Betty Criswell, known at the church as “Mrs. C.” The Criswells traveled many times with O.S. and Susie Hawkins, allowing the younger couple uncommon insight into their marriage and way of life.

That gives Hawkins credence to report what was rumored for years: The Criswells had an unusual marriage from beginning to end, and although often aloof from her husband, she defended him at the church at all costs. Hawkins describes Mrs. C’s spy network inside the church as rivaling J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI.

Norris and Truett

The book begins by explaining how Criswell, who was born in 1909, was raised mainly in the Texas Panhandle, graduated from Amarillo High School, went to Baylor University in Waco, Texas — where his mother accompanied him his entire freshman year — and then to Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky., where he met Betty and married her.

In his Baptist home, religion played a tremendous role, and the Baptist publications of the day were present and read religiously.

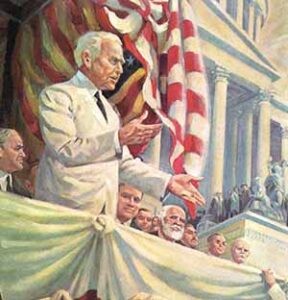

Edwin Hearne’s painting of George W. Truett delivering his 1920 address “Baptists and Religious Liberty” is part of the Eight Great Moments in Baptist History series. (SBHLA Image)

“As a boy, growing up there were two tremendous heroes in our house,” Criswell said. “My father admired Frank Norris and did it inordinately. … My father thought Frank Norris was the greatest preacher that ever lived. My mother was just the opposite. My mother thought Frank Norris was the Devil incarnate and that all he wanted to do was tear up our Baptist convention.”

Prescient words for a boy who would grow up to carry the same banner as Norris in reshaping the Southern Baptist Convention into the kind of fundamentalism Norris never achieved. What made Criswell successful where Norris failed is that Criswell on the outside imitated Truett more than Norris, Hawkins contends.

“Criswell lived his entire life with the two warring influences of Norris and Truett fighting for control within the inner recesses of his own heart and mind,” Hawkins writes. “He was an avowed fundamentalist when it came to theological and doctrinal matters, always elevating doctrinal loyalty above denominational loyalty. But at the same time, he fashioned himself after Truett when it came to avoiding personal conflicts and remaining above the fray as much as possible.”

“Criswell lived his entire life with the two warring influences of Norris and Truett fighting for control within the inner recesses of his own heart and mind.”

To that end, Criswell became a pro at enlisting other people to champion his causes publicly, Hawkins says. He worked effectively behind the scenes but seldom in public view.

When the “conservative resurgence” began in the SBC, it was started by two men under Criswell’s influence — Paige Patterson and Paul Pressler. Hawkins explains how denominational leaders begged Criswell to rein in Patterson, who at the time was on Criswell’s staff, and Criswell silently encouraged Patterson to keep going.

J. Frank Norris

Criswell remained a fundamentalist even when fundamentalism was going out of vogue in the SBC, Hawkins says. “Perhaps one of Criswell’s greatest contributions, and where he left a lasting influence, was that he made fundamentalist theology respectable. He brought it from the brush arbor back woods to the forefront of intellectual debate and theological thought.”

Cast of cameo characters

Hawkins delivers small details of Criswell’s life that will amaze Southern Baptist insiders, with cameo appearances by so many notable names that even Forrest Gump would be surprised:

- Who drove the getaway car when the Criswells were married in Louisville? None other than fellow seminarian Herschel Hobbs, who went on to become the legendary pastor of First Baptist Church of Oklahoma City and chairman of the committee that wrote the 1963 Baptist Faith and Message.

- Who played a significant role in Criswell getting to First Baptist Church of Chickasha, Okla.? None other than B.B. McKinney, the great gospel hymn writer.

- Who was favored to become the pastor at First Baptist Dallas to succeed Truett? None other than Duke McCall, who was then president of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary and went on to become president of Southern Seminary.

- Who encountered Criswell in Hollywood just as he was making one of the most famous movies of all time? Cecil B. DeMille, director of The Ten Commandments.

- What well-known moderate Baptist leader is a first cousin once removed from Criswell? David Currie, an early leader of a group called Texas Baptists Committed. His grandfather, W.G. Currie, was the brother of Anne Currie, W.A. Criswell’s mother.

The historic entrance to First Baptist Dallas. (Source: First Baptist Church)

Full of surprises

Part of the book is organized in chapters by decades, which provides a portrait not only of Criswell but of the church, which by some accounts was the first megachurch in Southern Baptist life.

The final chapter reveals Criswell’s three greatest regrets in life and ministry, which we won’t spoil here. The book contains so much detail over such a long span of time that it is impossible to even hint at all the gems in this single article.

Some things in the book you might not have known:

- Criswell in the late 1960s sought to change the name of the Southern Baptist Convention because he knew the word “Southern” was going to be a problem.

- When the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision legalized abortion, even though the case originated in Dallas, Criswell said nothing about it from the pulpit. In fact, like most Southern Baptist leaders of that era, he did not oppose abortion. That change of heart came later.

- When Criswell came to First Baptist Dallas in 1944, the church was full of white supremacists. Hawkins documents that dozens of First Baptist deacons served on the executive council for the Dallas chapter of the Ku Klux Klan — then the largest chapter in the United States.

- Criswell inherited a church staff of only five people serving a congregation of 3,000 to 7,000. One of his immediate goals was to build age-graded staff.

- One of the grand buildings erected on five city blocks in downtown Dallas during the Criswell tenure came to be without anyone else in the church knowing about it. With help from millionaire member Minnie Slaughter Veal, a five-story parking garage and family life center was built to Criswell’s specifications — with no church money expended — and then the keys handed over to Criswell.

- Regarding the infamous 20-month tenure of Joel Gregory Criswell’s successor at First Baptist Dallas: “No one knows the true motivation behind the Joel Gregory era of First Baptist Church in Dallas, but what I personally know is that following Gregory as pastor of the First Baptist Church was much easier because of what he endured.”

Why now?

In an interview, I asked Hawkins why he wrote the book now.

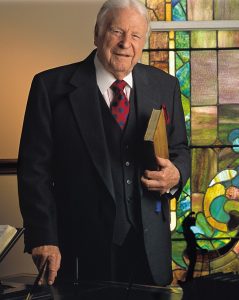

O.S. Hawkins

“The main reason … is that I promised him I would wait 20 years after his death to publish his autobiography,” Hawkins said. “He wanted to make sure certain people were dead and gone before some of his comments were made public since, in many ways in Baptist circles, he was one of the most polarizing figures of his time. I wanted to bring some balance into both extremes of perception of his life and ministry. Also, I wanted to introduce him to a new generation of church leaders.”

Criswell’s pastorate at First Baptist Dallas began in 1944, and he finally retired in 1994 at age 85. He died in 2002, having lived the last four years of his life at the home of his dear friend, Jack Pogue. One reason given for that change of location is that Mrs. C didn’t want to risk her incontinent husband soiling the expensive Persian rugs in their Swiss Avenue home filled with antiques.

Twenty-two years after his death, there are young ministers who do not know the name Criswell. Or if they do, they don’t know any of the stories.

Transcendent truths

I asked Hawkins what he finds transcendent in the pastor’s life and ministry.

“In today’s more informal church culture, we tend to look back and see him in his three-piece suits and starched shirt and tie as a relic from the past,” he responded. “But when you truly study his life, his genuine love for people no matter who they were or from whence they may have come is one of the transcendent features of his life we can take with us.

“I once heard someone say of someone else that they ‘never lost the wonder of it all in the work of it all.’ Criswell was the epitome of this statement. He kept a childlikeness about him without being childish — always in wonder of the work of God all around him in little as well as big things.”

Likewise, I wanted to know what of Criswell just wouldn’t fly today.

W.A. Criswell

“He openly and repeated used the words of the Apostle Paul to declare that he, as pastor, was the ‘ruler of the church’ referring to himself as a benevolent dictator. It is hard to imagine this approach getting very far in modern ecclesiology,” Hawkins said.

Indeed, the book documents the sweeping pastoral authority Criswell enjoyed, including the ability to hire and fire all staff on his own. Not to mention erecting an entire five-story building without the deacons knowing what he was doing.

Despite all this, Criswell and First Baptist Dallas accomplished things no other church could have done then or now.

“Churches are snapshots in time and not necessarily designed to perpetuate themselves over the decades,” Hawkins explained. “I can think of few churches that thrived through three levels of leadership. This was true with the Jerusalem church pastored by James and Peter, which although it reached thousands of converts to the faith was gone after 70 A.D. The same could be said of Charles Spurgeon’s Metropolitan Tabernacle in London. Within a decade of his passing, thousands of congregants had moved on to other places.

“Whether we like to admit it or not, churches after a few years begin to take on the personalities of their pastor. First Baptist Dallas is proving to be the exception to this ‘snapshot in time’ approach as it is still active and vibrant now through several levels of leadership.”

The chosen one

For decades, the question of who would be Criswell’s successor was a favorite conversation point not only for insiders at First Baptist Dallas, but for Southern Baptists nationwide.

Hawkins lays out the peril and promise of this succession chatter and devotes quite a few paragraphs to his own role in that drama. When Criswell finally got serious about seeking a successor, he wanted to name that person himself, which did not go over with the lay leadership of the church despite the carte blanch he otherwise held.

At one point, Criswell reported a vision from God that Hawkins, then pastor at First Baptist Church of Fort Lauderdale, Fla., was to be his successor. But the church instead appointed a search committee that became deadlocked for more than two years and finally made a rapid decision to call Joel Gregory from Travis Avenue Baptist Church in Fort Worth.

At one point, Criswell reported a vision from God that Hawkins, then pastor at First Baptist Church of Fort Lauderdale, Fla., was to be his successor.

That didn’t end well, and in short order after Gregory’s peculiar departure, Hawkins was installed as pastor and stayed four years.

I asked Hawkins about being the chosen one. He replied: “I am not sure I was the chosen one originally. The first time this speculation was public was in Joel Gregory’s book in 1994 when he said of Criswell’s London ‘vision’— ‘the faxes whined their mating calls. The phones buzzed. The letters flew. Everyone recognized the great unspoken designation. The mantle would be placed on Dr. O.S. Hawkins.’

“Criswell told others beginning with Jimmy Draper he could see them in the Dallas pulpit. He said this to Richard Jackson back in the 1980s, for example. It was his way of trying to encourage preachers, albeit a bit hyperbolic. If he was prophetic about anyone ‘picking up the mantle,’ it would have been about Robert Jeffress, his own ‘preacher boy’ who grew up there. I am honored he felt the Lord had put me on his heart as well.”

Of the Gregory saga — from which magazine articles, books and even a play have been written — Hawkins sees a teachable moment.

“The Gregory era should stand as an example for the transition of megachurches today,” he said. “By his own admission, Gregory, so eager for the Dallas pulpit, failed to ask many of the questions that could have and would have made the transition easier. In contrast, James Merritt was wise enough to not make such a mistake, did ask the hard questions of the pulpit committee and most likely did not receive the definitive answers that satisfied his inquiry. I actually sought to follow Dr. Merritt’s example in my dealing with the committee in 1993.”