The early morning air breathes hot on her face as archaeologist Cynthia Shafer-Elliott picks up her trowel to begin her work she describes as “not for the fainthearted.” Before her stands a mound of dirt, otherwise known as a “tel,” that holds within itself the remains of long-lost cities and towns.

These man-made hills can be found throughout the lands of Israel, Gaza, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria. In an interview with Peter Enns and Jared Byas on their podcast, The Bible For Normal People, Shafer-Elliott revealed that for her, “it’s the stories behind the artifacts, behind the architecture, the stories of the people that used these items and lived during this time that I find the most fascinating.”

Cynthia Shafer-Elliott and students from William Jessup University at an archaeological dig.

Every muscle in her body aches as Shafer-Elliott begins moving away the dirt, not expecting to discover anything that will change the world. Instead, she’s moved with the wonder of connecting with families long forgotten. She reflects, “You are the first person to uncover something that hasn’t been seen or touched in thousands of years.”

Because the cities and towns underneath these hills were built on top of one another over time, Shafer-Elliott explains, “when we excavate them, we are basically going back in time. So the most recent occupation of that city is at the top. And the further down you excavate, you are going through the different layers of when that city or town existed and what was left behind.”

This means if Shafer-Elliott wants to learn about a time period from the early formation of Israel, she will need to meticulously go through each of the more recent upper layers with the same level of care and documentation that she will one day give to the deeper layer she wants to explore. Even then, she may finally get down to the layer she wants to explore only to discover a few pots or lamps.

Cynthia Shafer-Elliott

But for Shafer-Elliott, that’s where the connection happens. It’s in those moments when blanketed by the hot summer air that she notices what appears to be the edge of a handle. As she brushes away the dirt, she finally can see the curves of a pot that a family once used to make their meals. While the pot was made by someone working on a wheel, the handle was pressed on. As Elliott further brushes the dirt away, she sees at the point where the handle connects to the pot, a thumbprint.

What happens after archaeologists make such discoveries?

We’ve all seen the movies where an archaeologist filled with innocent, child-like wonder gets used by someone with nefarious intentions who commodifies their discoveries for some self-aggrandizing end. Then there are the stories of forgeries and fakes that get bought and sold to unsuspecting collectors.

That’s only the beginning of the questions. There are layers and layers of other questions when it comes to faith claims about archaeology.

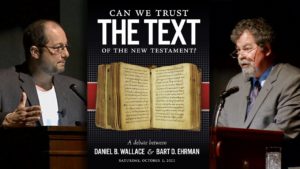

The showdown that became a letdown

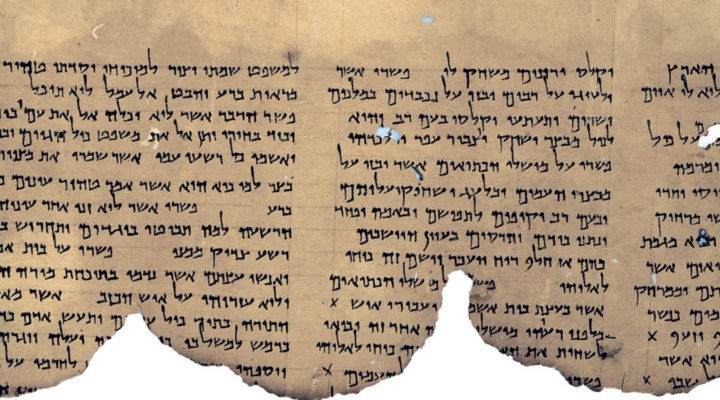

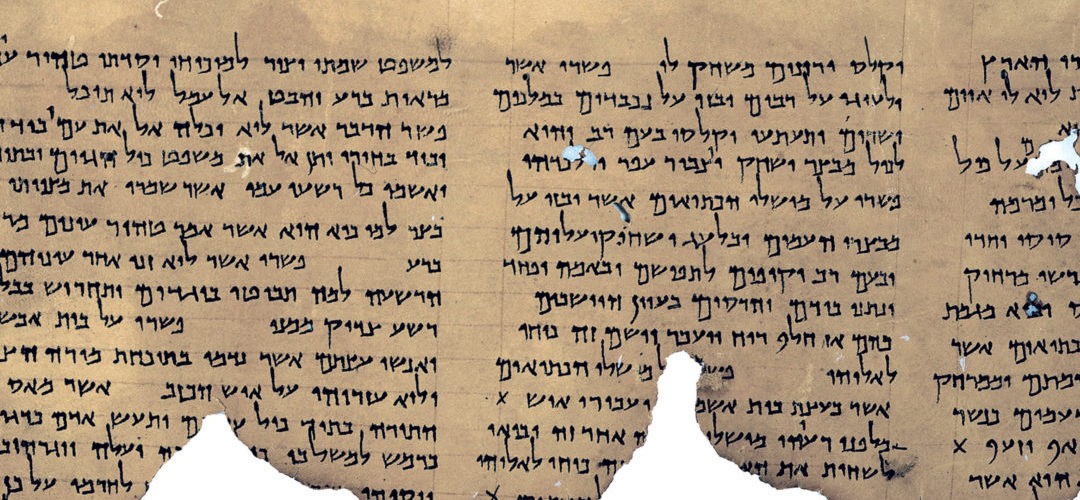

When inerrantists claim that the Bible contains no errors “in its original autographs,” other biblical scholars respond by pointing out that the original documents (called “autographs”) no longer exist and that the biblical texts we have today were pieced together and edited over time. But when Daniel Wallace of Dallas Theological Seminary prepared to face off against the agnostic professor Bart Ehrman on Feb. 1, 2012, Wallace had a surprise in store.

To the astonishment of the audience, Wallace announced that a first-century piece of the Gospel of Mark had been found, that he couldn’t name the expert who found it due to being “sworn to secrecy,” but that this expert was widely regarded as “the best papyrologist on the planet,” and that the discovery would be detailed in an academic book within a year.

To the astonishment of the audience, Wallace announced that a first-century piece of the Gospel of Mark had been found, that he couldn’t name the expert who found it due to being “sworn to secrecy,” but that this expert was widely regarded as “the best papyrologist on the planet,” and that the discovery would be detailed in an academic book within a year.

At the time of this meeting, Wallace had become a member of the Green Scholars Initiative, which was run by a family of evangelical billionaires who own Hobby Lobby and started the Museum of the Bible.

As Ariel Sabar detailed in The Atlantic, by the time the museum opened in 2018, the promised academic book had not been published. The world-renowned expert Wallace referenced turned out to be Dirk Obbink. But there was a problem with the story.

Steve Green

Evangelical scholars Scott Carroll and Jerry Pattengale were hired by Steve Green, president of Hobby Lobby, and they met with Obbink, who suggested that Green might want to consider purchasing the fragment of the Gospel of Mark that Wallace had spoken about.

Carroll soon reached out to Jeff Fish of Baylor University, who was unaware that the Baylor Institute for Studies of Religion was committed to become the home for the Green Scholars Initiative.

Scott Carroll

Soon, Baylor hired Carroll as a research professor. When he arrived at Baylor and began demonstrating to the students how to pull fragments of ancient documents from mummy masks with Palmolive dish soap, David Lyle Jeffrey, a former Baylor provost, realized something was wrong. He noticed that prior to Carroll’s demonstration, Carroll had placed the fragment that was supposedly coming from the mummy mask in the sink and simply pretended to pull it from the mask. It was a fragment from the book of Romans.

Within two days of this planted discovery, Steve Green was on CNN talking about how they had just discovered the oldest known copy of the book of Romans.

Within a few months, Carroll said Baylor would need to pay him more money if they would like to continue having access to the Green Collection, and he was fired soon after.

In hindsight, Baylor dodged a bullet twice, once with Carroll and once with Obbink.

Dirk Obbink

In time, Obbink’s reputation began to wear thin, and the Egypt Exploration Society demanded that he either stop working with the Green Scholars Initiative or lose his membership as one of their editors, which would cause him to lose access to their papyri and possibly his position at Oxford.

Although the Museum of the Bible continued paying him $6,000 a month as well as paying for his projects, Obbink claimed he no longer was working with the Green family. He then bought a home within a short drive of Baylor.

When a YouTube video appeared a year later in which Carroll was seen talking to a group of conservative evangelicals about the fragment of Mark supposedly discovered by Obbink and dating to around A.D. 70, the Egypt Exploration Society told Obbink he had “to prepare it for publication as soon as practicable in order to avoid further speculation about its date and content.”

But Obbink knew that in doing so, he would reveal to the Greens that he never had any right to sell the fragment, and that the actual dating he had given it was as late as the third century, rather than A.D. 70.

The Museum of the Bible soon would begin learning that Obbink’s suppliers lacked the necessary documentation for their supposed discoveries.

The Museum of the Bible soon would begin learning that Obbink’s suppliers lacked the necessary documentation for their supposed discoveries. And eventually Obbink would be fired from Oxford. In 2018, when Baylor was considering giving Obbink a full-time job with the possibility of tenure, Jeff Fish warned them against it. And Obbink never got the offer. He soon sold his house near Baylor to the evangelical reality TV stars Chip and Joanna Gains, while Steve Green gave 5,000 papyri to Egypt and 10,000 relics to Iraq.

Daniel Burke of CNN reported that the takeaway of Dead Sea Scroll expert Kipp Davis is this: “Evangelicals and others whose faith motivates them to collect artifacts should be very careful with antiquities dealers eager to pique their interest in supposedly ancient scraps of Scripture.” Burke quoted Davis saying, “These good intentions that draw from a place of faith are subject to some really gross manipulations. And that is a big part of what has happened here.”

Jesus was married?

But it’s not only faith-driven conservative evangelicals that fall for forgeries and fakes. In April 2014, the Harvard Theological Review released an issue focusing on a papyrus containing the phrase, “Jesus said to them, ‘My wife … .’”

Karen King

Karen King, a Harvard Divinity School professor, already had announced the papyrus, naming it, “The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife.”

Ariel Sabar tells the story in The Chronicle of Higher Education of how King ignored warnings from scholars that the papyrus might be a fake. With two of three peer reviewers calling her discovery a fake, her entire story rested on the testimony of papyrologist Roger Bagnall, who just happened to have been her adviser for the paper.

And the scientists she asked to study the accusations of her papyrus being forged were a close family friend and the brother-in-law of Bagnall.

While King claimed her discovery had been accepted through a normal external peer review, the entire story turned out to be a hoax.

When seminaries become the prey

One of the common groups that get caught up in these scams are seminaries. Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary had to release a statement in April 2020 saying that its previous leadership also had fallen prey to forged document fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Those relics were acquired by then-President Paige Patterson, who in 2018 was fired by seminary trustees for other reasons. However, concerns about these artifacts played a role in the overall criticism of his administration.

In April 2020, the new seminary administration issued a statement that said: “The Dead Sea Scrolls fragments were acquisitions of the prior administration. Because we have had very little confidence in their authenticity, the fragments have never been on public display since the arrival of the new seminary administration in February 2019. The fragments are in a secure location and have not been available to the general public in some years.

“As early as 2016, some seminary faculty had become convinced at least some of the fragments were possible forgeries.”

“The current administration’s lack of confidence in the fragments’ authenticity has been confirmed by an October 2018 report prepared for the seminary’s board of trustees by faculty associated with studying the collection. That report, which was recently provided to the current administration, found that by as early as 2016, some seminary faculty had become convinced at least some of the fragments were possible forgeries. More recently, the independent investigation of the Museum of the Bible’s Dead Sea Scrolls collection concluded its fragments were not authentic, which gives us even less confidence in our collection since they share a similar provenance to the MOTB collection.”

Because the prior administration already had spent so much money acquiring the fake fragments, current seminary officials said they lacked the necessary funds to investigate what happened. Additionally, they announced, “We will no longer offer degrees in archaeology because they are incongruent with our mission to maximize resources in the training of pastors and other ministers of the gospel for the churches of the Southern Baptist Convention.”

The desire to prove the faith

How does modern scholarship go from the reality of Cynthia Shafer-Elliott connecting across thousands of years with an ancient family through a thumbprint on a pot to the scandal of seminaries wasting millions of dollars paying international organizations that illegally traffic fake artifacts?

For many evangelicals, the desire to discover and spread ancient artifacts that confirm the events described in the Bible originates from a need to be believed.

Museum of the Bible

The nature of developing a view of reality based on faith opens all believers — but especially evangelicals — to believing the fantastic. If the events and miracles in the Bible literally happened, then many evangelicals assume the evidence that they lack to document the stories can be found if they simply look hard enough. Archaeology becomes a project in proving the Bible true.

The mounds of evidence that contradict a literalist reading of the Bible are then discounted as persecution from the scientific community or deception from the spiritual powers of darkness.

For example, the apologetics group Answers in Genesis claims that “no apparent, perceived or claimed evidence in any field of study, including science, history and chronology, can be valid if it contradicts the clear teaching of Scripture obtained by historical-grammatical interpretation.” Thus, their entire posture toward archaeology becomes defensive.

According to Ariel Sabar’s story in The Atlantic, the Museum of the Bible was meant to be a “Christian Smithsonian,” in contrast to the lack of scientific credibility afforded the Creation Museum or the Ark Encounter of Answers in Genesis. Yet when a scholar affiliated with the Museum of the Bible mentioned surprise fake artifacts during a debate that their executives thought would prove a vital claim of inerrantists, their posture toward archaeology was defensive.

Scholars on both the left and right have fallen victim to their own confirmation bias when it comes to archaeological finds related to Scripture.

Scholars on both the left and right have fallen victim to their own confirmation bias when it comes to archaeological finds related to Scripture. Within this branch of academia, there are beliefs to defend, egos to build, relationships to control, money to make.

Archaeologists like Cynthia Shafer-Elliott understand this. She told Peter Enns and Jared Byas: “Some people say, ‘You should be digging with your trowel in one hand and with your Bible in the other. And then you have others who say, ‘Absolutely not, because archaeology is its own discipline.’ And you have no other archaeology that uses a text to define or interpret its answers.”

For Elliott, archaeology is not about defending an agenda, but about meeting and loving neighbors across time. It’s about seeing the fingerprint of an ancient man on a pot that was used by a long-forgotten woman to provide food for her family struggling to survive their few short years under the sun.

Related article:

Shedding light on the Old Testament’s great villain — the Philistines