Before the pandemic, 1 in 3 families across the U.S. struggled to afford diapers. Now, with more than 56 million families with children losing their household income since March of this year, diaper banks trying desperately to assuage escalating demands are struggling to fill the need.

An often-hidden product of poverty, diaper need affects the physical, mental and economic welfare of children and families. The National Diaper Bank Network estimates that, at minimum, diaper banks are distributing monthly 50% more diapers to families in need than before COVID-19. Numerous more programs have reported surges of more than 400% to 500%. Programs in major cities are projecting that their respective diaper banks will distribute in excess of 2 to 7 million diapers by the end of 2020.

From the onset of the pandemic, diaper banks throughout the U.S. have pivoted and continued to adapt their distribution models. Many have shifted to drive-through and mobile diaper distributions in their communities. However, given the economic indicators for the fall and winter, it is expected that the unprecedented demand on diaper banks will continue without falter.

From the onset of the pandemic, diaper banks throughout the U.S. have pivoted and continued to adapt their distribution models. Many have shifted to drive-through and mobile diaper distributions in their communities. However, given the economic indicators for the fall and winter, it is expected that the unprecedented demand on diaper banks will continue without falter.

Why is there a need?

Troy Moore, chief of external affairs for the National Diaper Bank Network, explained that federal programs that low-income families rely on to help them pay for groceries —Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and the Women, Infants and Children Program — do not cover the cost of diapers. “In most of the country, diaper banks are the only option for families struggling with diaper need.”

Many parents across the country who are already struggling to afford basic living costs such as food and rent simply are unable to afford the high cost of an adequate supply of diapers for their children. A newborn baby can go through 12 diapers a day; an adequate supply can cost from $70 to $100 per month.

According to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, the poorest 20% of Americans buying diapers are spending nearly 14% of their post-tax income on diapers. Without transportation, purchasing diapers at an inner-city convenience store rather than a large retailer can double or triple the monthly cost for diapers; and in poor and low-income families scrambling to allocate limited income, a baby can spend a day or longer just in one diaper, leading to a multitude of potential health and abuse risks.

This accounts for 5 million children aged 3 or younger living in low-income families across the U.S. Providing diapers to families eliminates $4.3 million in medical costs due to reductions in both incidences and days of diaper rash.

The ripple effects of not having diapers

Low-income parents were most often unable to take advantage of free or subsidized child care if they couldn’t afford to leave disposable diapers at child care centers.

Even before the virus, low-income parents were most often unable to take advantage of free or subsidized child care if they couldn’t afford to leave disposable diapers at child care centers. If parents cannot access day care, then they are rendered less able to attend work or school on a consistent basis. This in turn leads to increased economic instability and a continuation of the cycle of poverty only exacerbated during the pandemic.

Being unable to provide the basic materials for one’s children can cause what Myra Jones-Taylor calls a “cascading effect.” Taylor, chief policy officer for Zero to Three, a nonprofit focused on the well-being of infants and toddlers, is a member of a national group responsible for tracking emotional wellness during the spread of COVID-19 through a weekly survey conducted by the University of Oregon. From the beginning of April, Taylor and other researchers surveyed 2,400 caregivers covering a wide socioeconomic scope. They discovered that when caregivers report financial and material troubles, they also experience emotional distress within a week. According to Taylor, in turn, the “caregiver emotional distress is linked to child emotional distress.”

Advocating for changes in public policy to meet the material basic necessities of low-income families, particularly in communities populated by Black, Indigenous and persons of color, is vital to addressing and combatting diaper need. The nonprofit sector alone cannot provide all the material basic necessities that children and their families need to prosper. Broad support from the government, companies and communities is required.

Seeking solutions

Rainbow Push Coalition partnered with the National Diaper Bank Network and its member diaper bank programs to run community-wide diaper drives and diaper distribution events. They also partnered in National Diaper Need Awareness Week, which was most recently held Sept. 21-27, to engage with state and national elected officials to collect, repackage and distribute diapers in local communities. The event offers individuals, organizations, communities and elected officials opportunities to engage in real conversations and fundamental actions to help end diaper need.

Last year, Reps. Rosa DeLauro (Ct.) and Barbara Lee (Calif.) introduced HR1846 the End Diaper Need Act of 2019, which they continue to push today. This year, Reps. Bonnie Watson Coleman (N.J.), Rosa DeLauro (Ct.) and Barbara Lee (Calif.) introduced the Improving Diaper Affordability Act during National Diaper Need Awareness Week to make the purchase of diapers tax-free.

A bipartisan request for $200 million in emergency funding to support diaper distribution programs remains on hold as negotiations on a new COVID relief package have stalled.

Currently, a bipartisan request led by Sens. Murphy (D-Conn.) and Ernst (R-Iowa) for $200 million in emergency funding to support diaper distribution programs remains on hold as negotiations on a new COVID relief package have stalled in Washington.

And now, even as programs like SNAP or WIC do not currently provide adequate funds for buying diapers, the recent attempt by the Trump administration to end food stamp benefits for nearly 700,000 unemployed people reflects a pattern of illogical, obtuse government action regarding federal assistance programs. This move, however, was struck down and condemned by a federal judge on Sunday, Oct. 18.

Chief U.S. District Judge Beryl A. Howell of Washington, D.C., condemned the Agriculture Department in a scathing 67-page opinion, for neither addressing nor justifying the impact of such a sweeping change which “radically and abruptly alters decades of regulatory practice, leaving states scrambling and exponentially increasing food insecurity for tens of thousands of Americans.” The judge concluded that the department’s failure to confront the issue renders the agency action “arbitrary and capricious.”

The need continues to escalate

While progress oscillates, efforts labor, demands soar, and negotiations in Washington remain stalled, children and their families suffer. Diapers are not a luxury, but an essential material that is becoming trivialized in the competition between human necessities, thus, increasingly difficult to afford — even before the pandemic.

Kelley Massengale of the National Diaper Bank Network says the problem isn’t how much existing diaper banks are utilized but rather the amount of resources available. Diaper need is a major public health concern impacting infant health, parental stress and families’ abilities to fully participate in society. Massengale says: “We need federal, state and local policies that address diaper need. It can take time to implement such policies. In the meantime, diaper banks need increased support so that they can continue serving their communities and grow to serve others.”

To find out more about donating diapers, visit the National Diaper Bank Network.

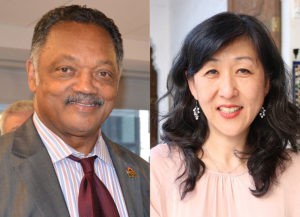

Jesse Jackson Sr. is an American civil rights activist, Baptist minister and politician. He is the founder and president of the Rainbow PUSH Coalition and author of Keeping Hope Alive. Grace Ji-Sun Kim is professor of theology at Earlham School of Religion in Richmond, Ind., and earned a Ph.D. from the University of Toronto. She is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA) and the author or editor of 19 books, most recently Keeping Hope Alive, Reimagining Spirit and Intersectional Theology co-written with Susan M. Shaw.