In 1990, in God’s Last and Only Hope: The Fragmentation of the Southern Baptist Convention, I wrote:

Growing up Southern Baptist once seemed relatively easy. Elaborate denominational programs created a surprising uniformity among an otherwise diverse and highly individualistic constituency. In churches throughout the American South, Southern Baptist young people were taught how to behave in church and in the world, on Sundays and throughout the week. Sundays meant church, all-day church. Off you went to Sunday school armed with the three great symbols of Southern Baptist faith: a King James Version of the Bible, a “genuine cowhide” zippered edition (white for girls, black for boys); a Sunday school quarterly outlining the prescribed Bible lesson; and an offering envelope containing the weekly tithe.”

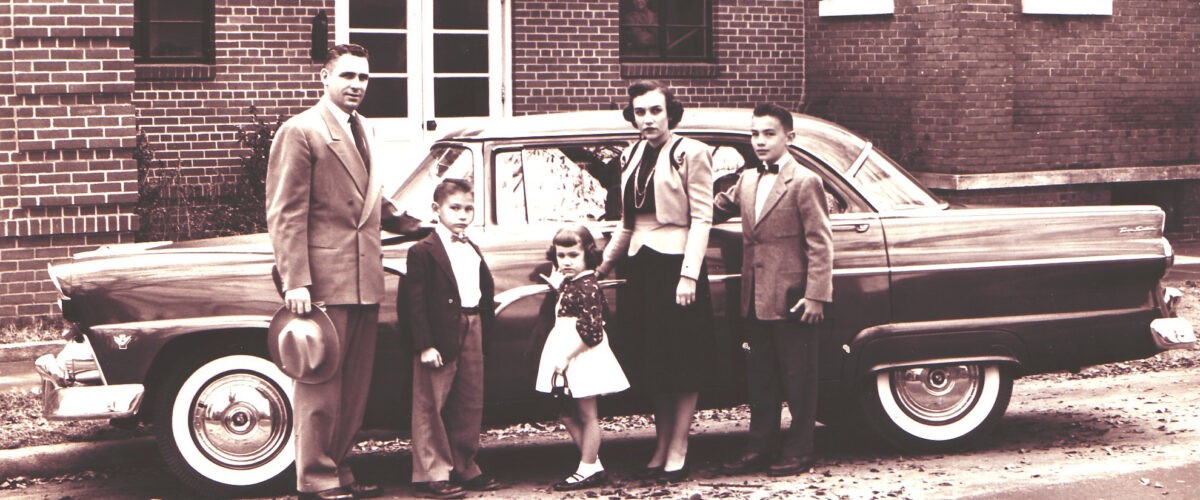

Bill Leonard

From childhood through early adulthood, Southern Baptist denominationalism inculcated, sometimes force-fed, Christian identity into me, nurtured through weekly worship, vacation Bible schools, fall and spring revivals, an elementary school-age baptism, and multiple adolescent “rededications,” throughout adolescence, finally “surrendering for full-time Christian service,” without the slightest idea of where that would take me.

I accumulated considerable mileage just “walking the aisle” in response to a variety of homiletical “invitations,” admonitions, demands, cautions and threats. In my teens, I eschewed alcohol, cigarettes, cussing and other forms of “worldliness,” meaning I never really learned to dance.

In The Lively Experiment: The Shaping of Christianity in America, historian Sidney Mead offered a classic definition of a denomination as a “voluntary association of like-hearted and like-minded individuals, who are united on the basis of common beliefs for the purpose of accomplishing tangible and defined objectives.” For Mead:

- Denominations were an ecclesiastical response to religious freedom, an alternative to European state-privileged religious establishments. Individuals were free to follow those groups that best exemplified their biblical interpretations or seemed closest to the “purity” of New Testament Christianity. Citizens were free to choose a denominational preference or none at all.

- Denominational survival depended on securing “volunteers,” thus denominational competition was inevitable.

- Denominations provided local congregations with a global awareness, emphasized through a mission to Christianize the world.

- Denominations offered “plans of salvation” detailing how sinners could find or be found by Christ, through the nurture of children or revivalistic conversion, ensuring new faith generations.

- Denominations offered programs, literature and a pervasive pietistic ethos for enhancing Christian maturity and spirituality, thus sharpening faith commitments.

Denominational programs and networks were major sources of Christian identity for generations of Americans, and Baptists were no exception. The title for my 1990 book came from a 1948 assertion by Alabama Baptist preacher Levi Elder Barton that, “The last hope, the fairest hope, the only hope for evangelizing this world on New Testament principles is the Southern Baptist people represented in that Convention.” He added, “I mean no unkindness to anybody on earth, but if you call that bigotry then make the most of it.”

“Denominational programs and networks were major sources of Christian identity for generations of Americans.”

Barton’s projections are not nearly so promising 74 years later. The SBC is now in its second decade of declining baptisms and church membership. A 2018 Christianity Today article reported: “Membership fell to 14.8 million in 2018 — its first time below 15 million since 1989 and the lowest it’s been since 1987. … In 2018, baptisms dipped by 3%, not as dramatic as the previous year when they were down 9%. Overall, Southern Baptists’ namesake practice has reached a historic low of 246,000 baptisms a year — around how many people were dunked by the denomination back in the 1940s, when it was less than half its current size.”

A 2019 Christianity Today essay noted: “For much of the ’80s and ’90s, Southern Baptist kids were pretty likely to grow up to become Southern Baptist adults: Seven in 10 maintained their SBC identity into adulthood in surveys conducted between 1984 and 1994. That has declined precipitously. In the most recent surveys conducted between 2015 and 2018, just over half of those raised Southern Baptist were still with the SBC. In other words, nearly half of Southern Baptists kids leave and never come back.”

Declines are not limited to the SBC. A 2019 headline in Faith+Leader from Luther Seminary asks, “Will the ELCA Be Gone in 30 Years?” pointing to studies suggesting that the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America “will have fewer than 67,000 members in 2050, with fewer than 16,000 in worship on an average Sunday by 2041.”

In a 2021 Religion in Public essay titled “The Death of the Episcopal Church is Near,” social researcher Ryan Burge writes: “One of the most troubling things about the future of the Episcopal Church is that the average member is incredibly old. The modal age of an Episcopalian in 2019 was 69 years old. With life expectancy around 80, we can easily expect at least a third of the current membership of the denomination to be gone in the next 15 or 20 years.”

“Denominations, once the primary way of organizing religious life in the United States, now seem in permanent transition.”

Denominations, once the primary way of organizing religious life in the United States, now seem in permanent transition, realigning, reassessing, reconfiguring, often statistically dis-membered, losing or unable to locate members, old and new. Amid those downturns, denominational resources for passing on Christian identity are undermined or lost all together, often to the detriment of congregations.

In his 2016 study, Identity the Necessity of a Modern Idea, historian Gerald Izenberg cites a 1963 analysis that, “When an age enters a time of radical transition, loss of identity ensues. Societies and civilizations which had enjoyed a clear sense of purpose and self-understanding seem to forget who they are.” Churches and denominations too, we might add.

In this new year, as denominational identities and numbers wane, congregations might ask themselves:

- Who are we as members of the body of Christ and how do we articulate or enact that Christian identity with each other and with those around us?

- How and why do we call persons to faith in Christ? Are we clear on how persons come to faith and grow in grace?

- In an era of necessary social distancing, how do we reclaim the intimate grace of baptism and Holy Communion?

- Are our mission statements, confessions of faith, church covenants or other theological documents understood by members of our congregations?

- Given the continuing realities of COVID and its variants, are there direct and/or virtual possibilities for offering studies in Scripture, theology, history, spiritual formation and pastoral care that might energize, instruct and enhance communal identity and relationships?

As 2022 begins, I find myself returning to thoughts I wrote in 1990, never imagining turbulent issues then would become more turbulent now: “An insistence on doctrinal certainty obscured the continuing confusion (among Christians) regarding the nature of Scripture, the meaning and morphology of conversion, evangelism, mission, ministerial authority, the priesthood of all believers, theological education and the nature of the church.”

So let us not confuse identity with uniformity. Like W.H. Auden’s “Double Man,” we sit “perched on some great arete (moral precipice), where if we do not move we fall. Yet movement is heretical, since over its ironic rocks no route is truly orthodox.”

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

Diana Butler Bass: SBC decline dispels idea that only liberal denominations die

Are denominational bodies doomed? | Opinion by Bill Wilson