Major stereotypes about HIV/AIDS and its victims persist despite decades of advancements in the knowledge and treatment of the virus and disease, said Stacy W. Smallwood, new executive director of the Faith COMPASS Center at Wake Forest University Divinity School.

Funded by biopharmaceutical manufacturer Gilead Sciences, the center is a project designed to equip faith leaders and religious communities with the capacity to address HIV/AIDS in the Southern United States.

Unfortunately, the center and its staff must devote significant time and effort addressing attitudes about HIV/AIDS dating back to the 1980s when the virus and disease burst onto the scene in the U.S., said Smallwood, who stepped into his leadership role June 1.

Stacy Smallwood

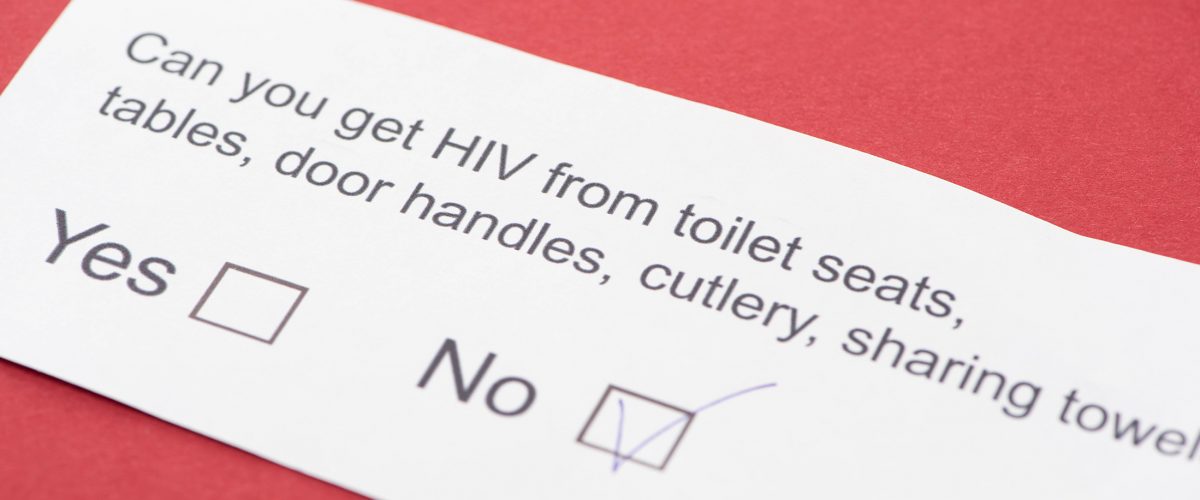

“Even with all the new tools, the new medications we have now, we’re still fighting an ’80s and early ’90s mindset with a lot of the stigmas, the different myths, misconceptions and misinformation about how HIV can be spread,” he said.

The virus is mainly spread through direct contact with semen, vaginal fluids and blood. Much more is known today about the precise transmission pathways than in the early days of the virus, when people feared being in the same room with an infected person.

But still, many people mistakenly fear transmission can come from saliva and other sources. “There are still people who won’t allow their family members to use their plates or utensils,” Smallwood said. “Or they’re scared that they might get it from a mosquito bite, or they’re scared that casual contact could spread it.”

And there are those who attempt to minimize the severity of HIV/AIDS by saying it’s simply other people’s problem or a problem limited to those who engage in illicit sexual behaviors.

Although you may not hear as much about it on the news, HIV/AIDS remains much more prevalent than most people believe, Smallwood explained.

“There are over a million people living with HIV in the United States and each year there are roughly 35,000 to 40,000 new diagnoses. Keep in mind that’s just diagnoses — there are a lot of people who have HIV who have not been tested and who have not been diagnosed.”

But the virus and the disease it causes also have social and geographical dimensions that must be addressed, he said. “African Americans make up about 13% of the U.S. population, but we make up about half of new diagnoses per year. When we think regionally, the South accounts for a little more than maybe one-third of the U.S. population, but we account for a disproportionate number of new diagnoses. So there are disparities based on race, there are disparities based on place.”

And there are disparities based on discrimination, Smallwood added. “In many ways, HIV also is a symptom of some of the larger prejudices that exist within our communities across the country. There’s definitely an overlap with racism, there is overlap with sexism and misogyny, there’s overlap with homophobia and transphobia. These societal ills help to exacerbate the disparities that we see in HIV diagnosis rates.”

“HIV also is a symptom of some of the larger prejudices that exist within our communities across the country.”

Prior to joining the Faith COMPASS Center, Smallwood was professor of community health and founding director of the Office of Health Equity and Community Engagement at Georgia Southern University. He also served as an affiliate faculty member in the university’s Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies program.

Smallwood brings extensive HIV prevention and treatment experience to the center. He has worked with faith groups in rural areas to boost awareness and prevention, launched programs to increase knowledge of pre-exposure prophylaxis among marginalized people and served with the American Public Health Association’s HIV/AIDS section.

“I’ve worked in several different aspects of this field. I’ve worked for community based organizations passing out the safer-sex kits and the literature to help people learn how they can stay safe. I’ve done occupational HIV prevention with needlesticks and sharps injuries in health facilities. I’ve done capacity building for community based organizations and also now my research has been largely at the intersection of faith and HIV, especially in Black communities and rural communities.”

Smallwood grew up singing in the choir of a Baptist church in Eastern North Carolina, led choirs throughout his higher education years and was as a minister in the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church.

“I come from a very deep and rich spiritual background as a Christian minister, someone who was raised in the church, but also understanding the importance of having a personal relationship with Jesus that has definitely undergirded all the work that I do.”

But it was as an undergraduate at Wake Forest University where his interest in public health evolved and became an avenue of ministry through illness prevention.

“This is why this opportunity to work for the Faith COMPASS Center feels like a full-circle moment. … I do consider this to be a calling and I work with a team of amazing individuals who also have indicated that they feel that this is part of their calling. We are here to meet a need that not everyone has the tools or the skills or the hearts to do.”

One of the tools the center uses to combat stereotypes about HIV/AIDS is storytelling, a method that gives victims voice to share their experiences in order to humanize their experiences for their family, friends and communities.

“We need to be able to provide the space for different kinds of narratives to shine light on the stereotypes, the prejudices and the myths in order to eradicate them,” he said.

The center offers numerous other programs, including one that educates cohorts of faith leaders and community members on the basics of HIV/AIDS, and another providing grants for the advocacy of faith-based groups.

With support from Gilead Sciences, which has committed $100 million overall to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the center is living into its calling to strengthen religious, community and health care leaders in the struggle against the epidemic.

And for Smallwood, that’s a spiritual mission: “Looking at Jesus, at the Gospels, Jesus was motivated to go to where the people who were the most marginalized were, the people who were the most dispossessed, the people who were pushed to the sides, the people that were deemed to be underprivileged by the majority.”