In my last column, I held up as a worthy example for us all, a textile worker in a small North Carolina town — the one in the floral shirt and white scarf, who chose to follow the urging of Norma Rae (the title of the film) and shut down her loom.

She resisted the owners and managers who had created that patriarchal, oppressive and unsafe workplace, the only one around where she could trade her labor for a chance to make a living. Her resistance gave permission to the others to follow suit, and 17 did. The weaving floor fell silent. They won. They beat The Man.

Richard Conville

But it doesn’t always work that way. Maybe not even most of the time. It was, after all, a Hollywood movie. Take August Landmesser for example, a German citizen and shipyard worker. There is a famous photograph of him on the Wiener Holocaust Library website (Also the Christian Science Monitor has on its website a July 1, 2015, article on Landmesser).

The photograph shows August in a huge crowd of his fellow workers at the Blohm and Voss shipyard in Hamburg. It’s 1936, and they are all saluting, for Der Fuhrer himself has come for the commissioning of a new vessel. But Herr Landmesser is not saluting, and he appears to be the only one.

That was not his only infraction of Nazi rules: he and Irma Eckler wanted to marry but could not because she was Jewish. They had two children, and the next year Landmesser was arrested for “dishonoring the race.” He was released in 1941, drafted into the German army in 1944, and shortly thereafter died in combat. Dissenters sometimes simply lose.

“Dissenters sometimes simply lose.”

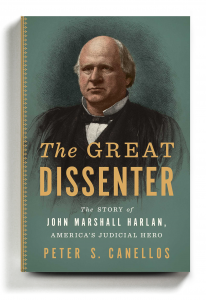

Another example of resistance is instructive. John Marshal Harlan’s dissent in the 7-1 Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) is considered by many to be the most famous and prescient Supreme Court dissent in all American history. He read it from the bench, making it all the more powerful.

“In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott Case. … The present decision … will not only stimulate aggressions, more or less brutal and irritating, upon the admitted rights of colored citizens, but will encourage the belief that it is possible, by means of state enactments, to defeat the beneficent purposes which the people of the United States had in view when they adopted the recent amendments to the Constitution” (referencing the 13th and 14th amendments).

But I’m getting ahead of the story. Homer Plessy, a Black citizen in Louisiana, brought suit against the state for a law passed in 1890 that required public transport facilities (trains and trolleys) to provide separate seating for Black and white passengers. Seating was to be assigned by race. The case made its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court and was heard on April 13, 1896. The court, by a 7-1 majority, affirmed the lower court’s holding that the Louisiana law was constitutional.

But I’m getting ahead of the story. Homer Plessy, a Black citizen in Louisiana, brought suit against the state for a law passed in 1890 that required public transport facilities (trains and trolleys) to provide separate seating for Black and white passengers. Seating was to be assigned by race. The case made its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court and was heard on April 13, 1896. The court, by a 7-1 majority, affirmed the lower court’s holding that the Louisiana law was constitutional.

Meanwhile, Harlan’s dissent rang out: “In view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful.”

With the court’s 1896 decision, the infamous and ultimately tragic phrase “separate but equal” ruled the day in the United State of America for the next 58 years, until the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. Plessy v. Ferguson created what we’d call today a “permission structure” for the violence and insults and disrespect of the Jim Crow Era; for Theron Lynd refusing to register Black citizens to vote in Forrest County, Miss.; for the redlining of neighborhoods by banks for decades; for the Agriculture Department’s discrimination against Black farmers for decades; for the institutionalization of second-class citizenship of Black citizens for decades.

Harlan’s dissent turned out to be prophetic. It did what prophets’ words always do: call us back to our roots. He reminded us that justice and freedom are what we love most about being Americans.

It took nearly six decades, but we at last heard his clarion call: “All citizens are equal before the law.” We need to hear his courageous dissent again — today — as never before.

Richard Conville is a retired professor of communication studies and long-time resident of Hattiesburg, Miss. This column was published in The Pine Belt News Sept. 5, 2024.