Did you grow up hearing the Civil War was fought over states’ rights, not slavery?

And how was the war referred to? Civil War? War Between the States? The War of Northern Aggression?

Then you were exposed to the Lost Cause version of history.

If you are a Southerner — or your parents were — it is almost certain you grew up with this mythology in your home, your school and your church. Challenging that story may seem to challenge everything.

My best friend said to me, “You’re asking me to give up everything I was taught from childhood.” And I said, “Yes I am. Look at how often the church has been on the wrong side of history.”

What is the Lost Cause? The opening paragraph of the foreword of Dixie’s Daughters states:

Late-19th-century Southern white polemicists, determined to venerate and vindicate their antebellum and Confederate “tap root,” crafted the Lost Cause myth. This integrated set of ideas argued that differing interpretations of states’ rights, not slavery, caused the Civil War and that the right of secession stood deeply embedded in American constitutional history. Lost Cause spokesmen sketched an idealized portrait of the antebellum South, one that romanticized white paternalism and African American slavery and glorified the valor of Confederate soldiers. They contrasted the supposedly faithful, contented and productive slaves of the Old South with their allegedly disloyal, troublesome and inefficient descendants, the freedmen and freedwomen in the New South.

Late-19th-century Southern white polemicists, determined to venerate and vindicate their antebellum and Confederate “tap root,” crafted the Lost Cause myth. This integrated set of ideas argued that differing interpretations of states’ rights, not slavery, caused the Civil War and that the right of secession stood deeply embedded in American constitutional history. Lost Cause spokesmen sketched an idealized portrait of the antebellum South, one that romanticized white paternalism and African American slavery and glorified the valor of Confederate soldiers. They contrasted the supposedly faithful, contented and productive slaves of the Old South with their allegedly disloyal, troublesome and inefficient descendants, the freedmen and freedwomen in the New South.

Does that echo what you heard growing up? It’s what I heard from my family and my teachers. My dad, born in 1904 in the southeast corner of Arkansas, and my mother born four years later in New Orleans, heard the same thing and passed on their convictions about states’ rights, scalawags and carpetbaggers and “separate but equal” segregation to me.

In the 1940s in First Baptist Church of New Orleans, my grandmother’s Sunday school teacher taught the “Curse of Ham.” The Confederate memorials in almost every Southern town reinforced the image of the brave and gallant Confederate soldiers defending their homeland, a claim we still hear today as the statues come down.

Historian Karen L. Cox, author of Dixie’s Daughters, calls it the whitewashing of history, and I think that’s a good term — more descriptive, perhaps more easily understood than “mythology.” It is most definitely not the story of Greek gods or King Arthur and the Round Table.

“I come from a family that was on the wrong side at the most crucial points in American history, and I have had angry moments each time I have stumbled upon another point where I was deceived.”

I come from a family that was on the wrong side at the most crucial points in American history, and I have had angry moments each time I have stumbled upon another point where I was deceived. Of course, growing up, I had no idea.

The beginning

To start at the beginning, my original American ancestor was a Puritan preacher, educated at Cambridge, who fled to America in 1636 at the tail-end of Winthrop’s fleet, the first “settled minister” in Connecticut. Five generations later — and six generations before me — in 1776 Yale-educated Jedediah Smith, a Tory minister in Granville, Mass., fled with his large family to the British colony of Natchez.

This stuff is footnotes in history books, yet I knew nothing of it. Our family story always started with the Civil War, the Confederate officer, the family connections to Jefferson Davis, plantation aristocracy claims, scalawags, carpetbaggers and those “damn Yankees.”

When genealogists embraced the internet in the early 2000s, my cousin shared his research with me, and I was stunned. That started my journey into the family history. My great-grandmother was the widow of a Confederate officer who died too young due to the deprivations of three years as a prisoner of war on an island in Lake Michigan, and she was recognized (not accurately) as the niece of Jefferson Davis.

She chaired the memorial association that raised the funds to erect the statue of Jefferson Davis in New Orleans (the first statue to come down there) and was a founding member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Living until the 1930s, she was a perpetuator of Lost Cause mythology right up until the end of her life, and her only daughter — my great-aunt — continued that legacy and that legend.

Perhaps you were like me, caught up in the romanticism of the antebellum South. I remember hiding Gone with the Wind behind my math book in the sixth grade, and then when I had read every book in the children’s section of the Texarkana library — where I spent most days of summer — I migrated to adult fiction, where I consumed the historical novels of the South by Frances Parkinson Keyes and Harnett Kane.

Dedication of Jefferson Davis Monument in New Orleans, 1911 (Wikipedia)

The image cracks

I had my first hint that things weren’t what I thought when my best friend from church went to Ouachita Baptist College — hardly a bastion of liberal intellectualism — my senior year of high school. She came home Thanksgiving with a crisis of faith, declaring that everything she had been told all her life at home, church and school was a lie.

This was 1958. We had just witnessed and our school was impacted by the integration of Little Rock Central High School. Orval Faubus — a states’-rights, segregationist demagogue — was our governor. Martin Luther King was already stirring up “good trouble” — “agitating” in my dad’s opinion — in Montgomery; and a Black church was burned in Texarkana, a fact that was kept completely out of the news for decades.

I entered Baylor the next fall, and before I ever arrived on the campus, I attended the BSU freshman retreat at Latham Springs, where one of the major speakers was the first ever Black summer missionary. Bill Lawson would go on to become a prominent pastor and Civil Rights leader in Houston, delivering a sermon at George Floyd’s funeral.

“He was the first Black person I had ever encountered outside of servants and laborers, and the encounter changed my life.”

He was the first Black person I had ever encountered outside of servants and laborers, and the encounter changed my life and set me on a path I have been on ever since, that “ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free.”

Dixie’s Daughters is not so much the subject of my presentation as its chief source. I discovered it in a citation in Robert P. Jones’ White Too Long — it’s the only scholarly book I have found on the history of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and its insidious role that laid the foundation for present-day white Christian nationalism.

Ku Klux Klansmen and their families stand along the driveway of Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta during a memorial service for the Confederate States’ war dead on Memorial Day. April 28, 1937. (Getty Images)

Our history

If you grew up in the South like me, if your family history was influenced by the narratives of the Lost Cause, examine your own story and listen for bits and pieces echoed today by white Christian nationalists. Perhaps you grew up in a small-town fundamentalist church. You left, but think about family and friends who stayed. Watch the news headlines. Listen.

“The preachers proclaimed the war’s righteousness and used the Bible to justify the institution of slavery.”

The women and the preachers were the staunchest believers in the righteousness of the Confederate cause. The women sent their husbands and sons off to war, and they needed to believe God was on their side and would bring their men safely home. The preachers proclaimed the war’s righteousness and used the Bible to justify the institution of slavery. They could hardly understand how and why they lost the war if God was on their side.

It wasn’t just those semi-literate Baptist preachers from the Southern backwoods. National Baptist, Methodist and Presbyterian denominations all split over the issue of slavery, and the Episcopal Church of the South was the church of the Confederate elite, including Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee. Even Catholic priests defended the Southern way of life.

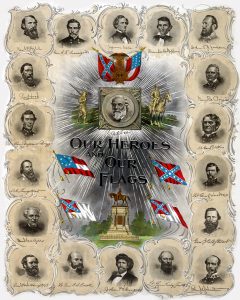

Memorial print for the Confederacy, published 30 years after the end of the American Civil War. Portraits, clockwise from top center, of “Jefferson Davis, Alexander H. Stephens, Lt. Gen. T.J. [Stonewall] Jackson, Gen. S. Price, Lt. Gen. Polk, Lt. Gen. Hardee, Gen J.E.B. Stuart, Gen. J.E. Johnston, Lt. Gen. Kirby Smith, John H. Morgan, Lt. Gen. R.S. Ewell, Gen. Wade Hampton, Gen. S. Cooper, Lt. Gen. Longstreet, Gen. Benjamin [i.e., Braxton] Bragg, Gen. Hood, Gen. A.P. Hill, [and] Gen. G.F. [i.e., G.T.] Beauregard,” surround the central image of Robert E. Lee, an equestrian statue, and four Confederate flags. Artist Tarr & Ross, 1895 (Photo by Pierce Archive LLC/Buyenlarge via Getty Images)

That really was what the Lost Cause was all about — looking backward to celebrate and vindicate and redeem the Southern white planter culture.

The widows like my great-grandmother were memorialists who raised funds to erect monuments to their husbands and heroes. It was largely the next generation, the daughters, who formed the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1894 with an expanded purpose and five primary objectives: memorial, historical, benevolent, educational and social. Rather quickly, this younger, more vindictive group swallowed up the memorial associations.

To place all of this in the context of the larger picture of American history, let’s back up a little. We don’t need a history of slavery in the South or the Civil War. We know how that ended. But it would be helpful to briefly review Reconstruction, that period from 1865 to 1876 that gave Blacks the right to vote and hold office in the South, and then take a somewhat longer look at the period that followed, up to the Spanish-American War in 1898 and even World War I — an era when the Union wanted reconciliation but the South sought redemption.

“The Union wanted reconciliation but the South sought redemption.”

Earlier I referenced carpetbaggers and scalawags. Those pejoratives were part of the family conversation, and as a small child I loved saying those words. I googled the term and found a history lesson plan that succinctly sums up Reconstruction.

Following the Civil War, much of the South was left devastated and in need of repair. This began the period known as Reconstruction. Many Americans from both the North and the South saw this as an opportunity. For some, it was an opportunity to help formerly enslaved African Americans. For others, it was an opportunity to advance their own economic or political interests. In the South, the derogatory nicknames of “carpetbaggers” and “scalawags” were given to them.

A carpetbagger was the name given to a Northerner who moved to the South during Reconstruction. The name was meant to suggest that the individual was so poor, he or she could fit all of their belongings in a meager carpet bag. However, carpetbaggers tended to be well educated and middle class. Southerners were generally resentful of these newcomers who they saw as profiting off of their defeat.

Many, however, moved South with good intentions. A lot were teachers or religious missionaries looking to help continue the struggle for racial equality. The Freedmen’s Bureau employed many to help formerly enslaved Black men and women. Most supported the Republican Party and were instrumental in electing the first African Americans to office, including Hiram Revels, the first Black member of Congress.

Scalawags were white Southerners who supported the policies of Reconstruction. This meant that they backed the Republican Party or assisted Black freedmen and Northern newcomers. Therefore, the majority of Southerners saw them as traitors.

Former Confederate soldiers were disenfranchised at the beginning of Reconstruction because they had not yet taken an ironclad oath of allegiance to the Union. This gave incoming Northerners more political power. “Scalawags” teamed up with Black men to run for office. In addition to Hiram Revels, 15 other African Americans served in Congress during Reconstruction and over 600 more were elected to state legislatures in the South.

You may vaguely remember the contested presidential election of 1876 between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel Tilden. To get the votes necessary to make Hayes president, Congress agreed on a compromise that withdrew federal troops from the South and effectively ended Reconstruction.

This is an explanation from the history lesson plan:

Unfortunately, both scalawags and carpetbaggers became targets of the terrorist group the Ku Klux Klan. White supremacists used intimidation, terrorism and violence against Black voters and their allies to reduce Republican voting and force officeholders out. As former Confederate soldiers began to vote again, a coalition known as the Redeemers came together to regain political power and enforce white supremacy.

My great-grandfather, a small-town lawyer, mayor and newspaper owner, was running for Louisiana secretary of state as a Democrat when he died in 1878, at the age of 42.

On June 4, 1917, Daughters of the Confederacy unveils the “Southern Cross” monument at Arlington National Cemetery. (Getty Images)

This is in the news right now. This is what the statue in Arlington Cemetery and its removal is all about.

Cox writes:

The Confederate monument at Arlington National Cemetery, more than any other built by the UDC, symbolized the South’s longing to be recognized as patriotic by the rest of the nation. This monument, they believed, would serve notice that the region’s defense of states’ rights was not a defense of slavery, but evidence of a commitment to constitutional principle. It was also intended to serve as a token of reconciliation with the North. For the Daughters, reconciliation could occur only when Confederate men had been vindicated. The federal government had, for all intents and purposes, met the Daughters’ conditions for reconciliation when it allowed the burial of Confederate soldiers in the cemetery and gave the UDC permission to build a monument to honor those soldiers. … (To show how eagerly the federal government embraced the idea, it) “was proposed by President William McKinley; Congress authorized it; and another President, William Howard Taft, oversaw the laying of the cornerstone. (President Woodrow) Wilson, therefore, saw his part in this chain of events as fitting, and he expressed pride in being able to participate in a ceremony that drew Northerners and Southerners together.”

I should note there’s a significant amount of evidence that Wilson was a racist and initiatives taken during his administration contributed to Jim Crow. Something else I wasn’t taught, not even in my upper-level course on modern American history.

But back to the monument at Arlington Cemetery. It’s a graphic representation of the purpose of the UDC.

Clint Smith recently wrote in The Atlantic that:

The statue was paid for and erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, a group of Southern white women who were the wives, widows and descendants of Confederate soldiers. The organization was responsible for erecting hundreds of Confederate monuments across the country in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was built by the sculptor Moses Jacob Ezekiel, a former soldier in the Confederate army, and unveiled by President Woodrow Wilson on June 4, 1914, which was the day after the 106th anniversary of the birth of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The statue’s most dominant image is of a woman — symbolizing the South itself — who wears an olive wreath atop her head. The monument also features depictions of two Black people that reify the subservient positions they occupied under slavery and the Confederacy. Arlington National Cemetery acknowledges:

“For decades, Southern politicians claimed that the statue was simply a part of a larger project of reconciliation, a way for political leaders to solidify national unity at a time when the wounds of the Civil War were still fresh. In some ways, they were right. It was intended as a symbol of reconciliation and unity. But for whom? Certainly not for Black Americans, who, in the decade leading up to the erection of this statue, had been terrorized by more than 700 lynchings across the country.”

The United Daughters of the Confederacy did not conceal what they meant by reconciliation. To them, reconciliation meant demanding that Reconstruction — which is to say, any efforts oriented toward pursuing Black social, political or economic equality — was acknowledged to have been a mistake. The best way to achieve national unity, they thought, was to allow Southern white people to govern themselves, with no repercussions from the federal government for the routine torture, destruction and murder of Black people.

This was redemption, and memorializing the fallen heroes of the Lost Cause was the first objective of the UDC.

Postcard of Dallas Confederate monument

Monuments

In Dallas, where I now live, it shocks me that one in three voters (white males) in Dallas County was a member of the Klan in the 1920s. I read somewhere of a rally that had a humongous crowd — 25,000 or perhaps 75,000? Whatever, it’s unbelievable.

We now understand how segregationist motives contributed to significant infrastructure decisions here and elsewhere. Collin Yarbrough has written about this in his excellent book, Paved A Way. Long before Collin, in 1986 a young Dallas Times Herald reporter named Jim Schutze wrote The Accommodation: The Politics of Race in an American City. The city fathers saw that publication ceased and existing copies were destroyed. Today, it’s available on Amazon. And if you haven’t read it, you should.

Cox describes the unveiling of the Dallas Confederate monument in Pioneer Park in 1898.

“The Dallas monument was unique, containing a central figure of a Confederate soldier, at the four corners of which stood life-sized figures of Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and Albert Sydney Johnston. Jefferson Hayes Davis, grandson of the Confederate president, was chosen to pull the cord that revealed the figure of Jefferson Davis. Lucy Hayes, another of Davis’s grandchildren, pulled the rope that revealed Lee’s likeness. Stonewall Jackson’s grandson unveiled the statue of Jackson, while his granddaughter revealed that of Johnston. Young women from the community, UDC members and veterans unveiled the remaining central figure of a Confederate soldier.”

To give you an idea of what a grand event it was, “Confederate veterans and their wives ‘from every town in Texas’ attended what was described as a ‘lovefest’ in their honor. The governor was there, as were members of the Texas Legislature, which had ‘closed its doors, that her lawmakers might come.’ The city of Dallas was decorated with American and Confederate flags.”

That statue came down in June 2020.

The Robert E. Lee statue was featured in a 1940s-era postcard promoting the city of Dallas. (Photo by Found Image Holdings/Corbis via Getty Images)

The grand equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee, in renamed Lee Park with its three-quarter replica of Arlington Hall, was a far more egregious offense. My first condo in Dallas faced Lee Park, at the corner of Lemmon and Turtle Creek. If this stretch of Turtle Creek was not part of Freedman Town, it was very near. The railroad tracks, now Katy Trail, formed the eastern boundary of Turtle Creek Parkway, and “Uptown,” on the other side — the wrong side of the tracks — was part of Freedman Town. The historic Black cemetery was about five blocks from the park.

Construction of Central Expressway, when the cemetery was bulldozed, separated the area from the rest of the Black community. Oak Lawn Park had been there since 1892. So with all the neighborhoods and boulevards available in Dallas — why not Swiss Avenue? — why was this park in this location chosen?

The park’s name was changed and President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated the statue in 1936, and it finally came down in 2017. The plinth has finally been removed, and the new name, Turtle Creek Park, was recently carved in the stone. Arlington Hall remains — perhaps name recognition is too low to cause controversy — and the street in front of Arlington Hall is still named Lee Parkway.

In my recent research I learned that Joe Lambert Jr., the legendary Dallas landscape architect who moved to the city from Shreveport in 1933, designed and apparently donated the Hibiscus Fountain in the park as a “memorial to Southern heroes.”

“With the outbreak of World War II, Southern states donated land for military bases in exchange for naming them after Confederate generals.”

And the monument-building and memorializing didn’t stop in the ’30s. With the outbreak of World War II, Southern states donated land for military bases in exchange for naming them after Confederate generals.

A stained-glass window honoring Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, a Confederate general during the American Civil War, installed at the Washington Cathedral is seen June 29, 2015, in Washington, D.C. The window now has been replaced.. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

And then there were the stained-glass windows at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. The Confederate battle flags were removed in 2016, and a year later the Cathedral decided to remove large windows depicting Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, which were donated by the UDC in 1953. Replacement windows finally were installed last fall. Our friend Greg Garrett was there.

You may think I am spending too much time on monuments. What do they have to do with white Christian nationalism? But quoting Cox again, “The Daughters were chiefly responsible for the movement to honor the Confederate generation, and their role as shapers of public memory cannot be overemphasized. The monuments that cover the southern urban landscape and sites of national significance are central to an understanding of the Lost Cause as a movement about vindication and the preservation of conservative values.”

We only have to look at the angry and even violent responses to the statues’ removal to see just how successful the UDC’s efforts were. We don’t see statues to Hitler and Rommel and Goring in Germany, but we still defend these West Point graduates who violated the oath they swore upon graduation: “I, __________, appointed a _______ in the Army of the United States, do solemnly swear, or affirm, that I will bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and that I will serve them honestly and faithfully against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever, and observe and obey the orders of the president of the United States, and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to the rules and articles for the government of the Armies of the United States.”

They weren’t heroes. They were traitors.

Re-education

I don’t think we can separate UDC goals into five distinct objectives. The monuments had both historical and educational functions, and there’s no way to separate the history from the education; so let’s spend our remaining time on this. Quoting Cox again:

Lost Cause Women believed that it was their duty “to instruct and instill into the descendants of the people of the South a proper respect for … the deeds of their forefathers.” Lost Cause men and women wrote tomes about the importance of teaching the younger generation the “true history” of the Confederacy; (their) Constitution implied that the Daughters intended to take further steps to actively “instruct and instill” in future generations of Southern white children the values of Confederate culture.

“UDC members aspired to transform military defeat into a political and cultural victory, where states’ rights and white supremacy remained intact.”

They did so not simply to pay homage to the Confederate dead. Rather, UDC members aspired to transform military defeat into a political and cultural victory, where states’ rights and white supremacy remained intact.

When I started doing genealogy, I was surprised by the quantity and quality of resources available. The LSU library’s Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections are the largest in the country, and my great-grandmother donated 363 letters to the collections. The Louisiana State Museum has the family portraits. I spent hours not only in the LSU library but also in the Natchez and Baton Rouge genealogy libraries and the Mississippi and Louisiana State Archives, and both states have scholarly historical associations that publish journals, in addition to the Southern Historical Association and its journal. The LSU Press’ publication of regional history is outstanding. Even my Corpus Christi genealogy library has every issue of The Confederate Veteran, and Rice University has spent 48 years publishing the papers of Jefferson Davis.

None of this is by chance. The UDC actively encouraged its members to collect and donate memorabilia of the Old South and lobbied the Southern states to establish archives. What I describe finding in my research is true in every former Confederate state. The Daughters have left reminders of the Old South everywhere.

Demonstrators outside West End High School in Birmingham, Ala., sing “Dixie” as a student plays the tune on a trumpet during an anti-desegregation protest in 1963. (Getty Images)

They didn’t stop there. They actively sought to indoctrinate Southern children through what they were taught in the schools — and that included influencing textbooks and teachers — and what they learned at home, reinforced by local Confederate youth groups.

In 1903, Adelia Dunovant, president of the Texas UDC, gave a speech at the national convention. Deploring the “very grave error” of branding Confederates as “rebels,” she said: “History should be made to serve its true purpose by bringing its lessons into the present and using them as a guide to the future. What lies before us is not only loyalty to memories, but loyalty to principles; not only building of monuments but the vindication of the men of the Confederacy.”

According to Cox,

UDC members generally applied such modifiers as “correct,” “authentic,” and “impartial” to describe a history that was favorable to the Confederacy. Their commitment to historical “truth” was firmly established in the UDC constitution, and much of the organization’s activity focused on meeting this objective.

The Daughters believed that an “authentic” history of the “War between the States,” their official term for the Civil War, would help them achieve important objectives. What counted as “authentic,” of course, was generally history written with a pro-Southern slant. History written “correctly,” they reasoned, vindicated Confederate men, recorded the sacrifices of Confederate women, and exonerated the South. “Biased” history, on the other hand, regarded secession as an act of rebellion and argued that the South fought the war to defend slavery. …

… moreover, they insisted, Confederate soldiers were American patriots because they were the true defenders of the Constitution. …

Vindication was not limited to rehabilitating Confederate manhood. Many Lost Cause devotees, including the Daughters, believed that biased histories had both maligned the Confederacy and generated false impressions of Southern life before the war. According to UDC members, non-Southerners had been misled into believing that citizens of the Old South were impoverished and illiterate. Even worse, for them, books like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin had successfully challenged whether the Old South elite were the true Christians, given that they had owned slaves. Lost Cause organizations were particularly defensive about the latter subject, because they regarded planter benevolence as inherently Christian.

They could not accept that the institution of slavery was evil, and so they perpetuated the myth of kind masters and happy, faithful servants. They ignored and even erased evidence from official records that white Southerners, especially poor subsistence farmers in border states, opposed secession and some, along with about 90,000 enslaved men, fought for the Union.

“By the 1920s, most Southern states had adopted Lost Cause textbooks and this was largely unchanged for 50 or more years.”

At their peak, before World War I, Daughters were continuously in the schools, hanging portraits of Confederate heroes and commemorating them on their birthdates, sponsoring essay contests and keeping an ever-watchful eye on the textbooks and the teachers. By the 1920s, most Southern states had adopted Lost Cause textbooks and this was largely unchanged for 50 or more years.

In the 1990s, the majority of white Southerners still believed the Civil War was fought over states’ rights, not slavery. This is still the official position of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

Leery of school teachers from the North, they encouraged the states to establish teachers’ colleges. My mother, in the late ’20s, graduated from “normal school,” a two-year extension of the New Orleans school system for training teachers.

The Daughters sought acceptance of their myths beyond the South, and while they largely failed, they had a singular success with a Reconstruction history professor at Columbia University. William Archibald Dunning was born in New Jersey in 1857, earned his Ph.D. from Columbia in 1877 and taught there until his death in 1922. The “Dunning School of Reconstruction” claimed reunification of the North and South was only achievable via the principle of white supremacy and denounced the Republican Party for giving Blacks the vote.

The Daughters sought acceptance of their myths beyond the South, and while they largely failed, they had a singular success with a Reconstruction history professor at Columbia University. William Archibald Dunning was born in New Jersey in 1857, earned his Ph.D. from Columbia in 1877 and taught there until his death in 1922. The “Dunning School of Reconstruction” claimed reunification of the North and South was only achievable via the principle of white supremacy and denounced the Republican Party for giving Blacks the vote.

According to Columbia’s website, the Dunning School had a white supremacist agenda and dominated 20th century academia. I was curious about my two American history professors, one of whom had made a courageous early call for the integration of Baylor. He was no racist. Sure enough, both my professors were from the Deep South and did graduate work at Vanderbilt, where one of Dunning’s most influential proteges, Walter Lynwood Fleming, taught. I guess they didn’t teach me because they didn’t know either.

And if all that wasn’t enough, local chapters of the UDC established Children of the Confederacy groups with a catechism with memorized “right answers” (Why was the War Between the States fought?), history lessons, the singing of Southern songs and benevolence projects for the residents of Confederate veterans’ homes and the like.

My cousin, five years older than I, remembers our great-aunt dragging him to those meetings at the Confederate Memorial Hall, where the world’s second-largest collection of Civil War memorabilia is allegedly housed. It’s an ugly pile of red brick, built in 1891, directly across the street from the World War II Museum, and around the corner from what was called Lee Circle, with Lee atop a tall column, facing north toward the “damned Yankees,” a story I heard every time we rode by the streetcar.

In addition to seeing that proper textbooks were used, the women wrote essays, biographies of Southern heroes and memoirs of antebellum life. Cox notes: They also wrote about Reconstruction and its effects on the South, about Southern women’s role during the Civil War, and about what they saw as the region’s rescue from ‘negro rule’ by the Ku Klux Klan. Vindication was always the goal.

While today most of us see the Klan as a lawless, terrorist hate group, to many Southerners the Klan was responsible for restoring law and order and they were welcomed as “redeemers.”

“In her view … former slave owners had done the world a service by providing their African slaves with the gift of Christianity.”

Especially important for us in the church to understand, Cox writes that longtime UDC historian Mildred Rutherford’s “personal crusade was to correct what she believed were false impressions of Southern slavery as harsh and cruel. ‘Slavery was no disgrace to the owner or the owned,’ Rutherford argued. She defended the institution for its ‘civilizing power’ over Africans brought to the Southern colonies. In racist language, she described how former slaves were ‘savage to the last degree’ and contended that contemporary Blacks should ‘give thanks daily’ that they were not now living in the land of their ancestors in Africa. In her view … former slave owners had done the world a service by providing their African slaves with the gift of Christianity. Indeed, she argued, the Old South planters should be recognized for having participated in ‘the greatest missionary and educational endeavors that the world has ever known.’”

‘Do-gooders’

As an extension of this attitude, consider the other two objectives of the UCD — social and benevolence.

While it is a lineage-based organization like the Daughters of the American Revolution and Colonial Dames, local chapters controlled who became members, and it was an elitist organization of the wives and daughters of the most prominent business and professional men in town. That gave them access to mayors, governors and even presidents and helps explain their political influence. They were entertained in the White House more than once.

In reading between the lines, I think the images we have of “Southern ladies” stem from the image they sought to project. Metaphors like “steel magnolias” and “velvet-covered fists” are apt descriptions.

Befitting Southern ladies, they were “do-gooders.” They established homes for Confederate veterans, continuing the volunteer activities the first generation extended to the soldiers during the Civil War. My great-grandmother, for instance, met her husband when he was first imprisoned in New Orleans. The young ladies regularly called on the imprisoned officers, taking them food, helping with letter-writing. I am sure their daughters saw their hours in the schools and on education and textbook committees as a continuation of their mothers’ volunteer work. I am equally sure they were as active in their churches as they were in their schools. I can almost hear the children’s Sunday school lessons.

“The UDC was never as strong again afterward, especially as the Civil War generation died, but its influence in the classroom was pervasive and lasting.”

Both the Spanish-American War and World War I contributed to the national desire and need for reconciliation and genuine reunification, and the wars provided ways for Southerners to prove their patriotism and for the Daughters to volunteer. The UDC was never as strong again afterward, especially as the Civil War generation died, but its influence in the classroom was pervasive and lasting. I would argue this is the best explanation for present-day white Christian nationalism.

Cox very neatly summed up the results of the UDC’s work:

The generation of children raised on the Lost Cause and Confederate culture in the early decades of the 20th century is also the generation that was actively engaged in massive resistance to desegregation at mid-century. …. From the generation came James O. Eastland, Strom Thurmond, Bull Conner, Byron de la Beckwith, and others. …

The UDC’s effort to plant seeds for reverence of states’ rights and white supremacy among Southern youth bore fruit during the fight to preserve Jim Crow, as a new generation of men and women employed the rhetoric once associated with the Lost Cause. The Citizens’ Councils, organized throughout the South in the 1950s and 1960s, employed that rhetoric and used tactics very similar to those of the UDC to defend their cause — the preservation of “states’ rights and racial integrity.” Just as members of Lost Cause organizations like the UDC used the language of states’ rights to justify slavery and de jure segregation, the Citizens’ Councils used it to react to the advancement of Black civil rights in their own time.”

And we know what the next generation is doing today.

I remember a few years ago I was surprised when I realized these people are anti-democracy. They don’t want one person, one vote. They don’t want majority rule. And they are willing to break the law and resort to everything from purging voter rolls to violence to get their way.

Confederate flag sympathizers, including Bonnie Mullins of Temple, Ga., center, protest what they believe is an attack on their Southern heritage during a rally at Stone Mountain Park in Stone Mountain, Ga., on Saturday, Aug. 1, 2015. (John Amis/Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP)

I still struggle

I write with seeming authority, but I must confess I struggle on many of the issues. The older I get, the less I see in black and white, and of course I cannot ever completely escape the lies I was told from birth. I am uncomfortable with the stark choices of:

- Reconstructionist or Redemptionist

- Jones’ choices between democracy and the Doctrine of Discovery.

- Hardest of all, Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning, originally on Greg Garrett’s list and an authoritative voice for Black historians. He argues if you aren’t actively working for integration, you are a racist.

As a Christian, I am firmly against the position of the Doctrine of Discovery, Redemptionists and white Christian nationalists. And yet … I can’t accept the idea that Providence or Divine Providence has played no part in our history.

And I wonder if all the memorials need to come down.

In fall 2017, I visited Gloucester, Va., in the Middle Peninsula, which Union forces occupied off and on from the very beginning of the Civil War. The town has created a wonderful historic center and walking trail, and there’s a simple town monument to its Civil War dead and a monument to the local African American who fought for the Union and received the Medal of Honor.

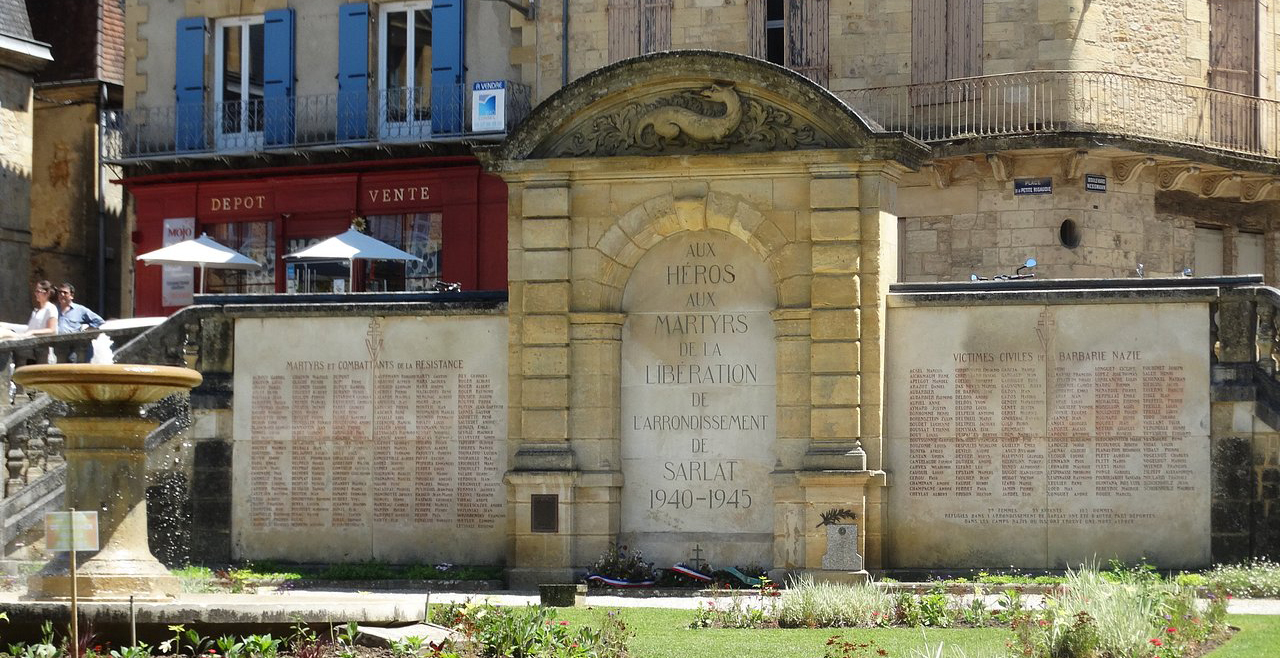

Monument aux Morts, Sarlat, France (Trip Advisor)

The next spring, I spent a week in the village of Sarlat, in the Dordogne region of southwest France. This was the heart of the French Resistance to the Vichy government and Germany in World War II. There, the town war memorial, which lists the dead from all the wars, includes both Vichy and Resistance fighters.

“We grieve our dead whether they were right or wrong.”

My reaction is that we grieve our dead whether they were right or wrong, and I see these memorials somewhat differently than I see the huge monuments erected by the UDC honoring Davis and the generals.

I don’t see racism as either/or. I see it as a spectrum. I’m not willing to erase the names of Washington and Jefferson from buildings simply because they owned slaves. I believe we need to judge people by the morals of their day and by the whole of their lives. And perhaps a rationalization, I can’t label my parents with the same label as cross-burning, night-riding. lynching Klan members. They never said the n-word or told a racist joke. They were outspokenly anti-Klan. They acknowledged “separate but equal” wasn’t really, and they pointed out the failures to me. They were products of their time and place and their limited education.

I wonder what is so wrong with having your wedding at a restored plantation mansion or garden as long as the couple isn’t re-creating an antebellum pageant. University buildings, historic churches and the U.S. Capitol were built on the backs of enslaved laborers or the profits gained from the slave trade.

And finally, a completely fact-based struggle. Back to the Dunning School of Reconstruction. I was taught all my life that the formerly enslaved were not qualified to hold office and that Reconstruction was a disaster. It’s true that after about 1825, Black Codes in the South forbade the education of the enslaved. Very few were educated. But was Republican Reconstruction government in the South a failure or a success? I don’t know.

“We don’t know what America would look like today if Reconstruction hadn’t been halted.”

Reconstruction is still unfinished business. We don’t know what America would look like today if Reconstruction hadn’t been halted prematurely. We don’t know what Africa would look like without slavery and colonialism. We don’t know what Latin America would look like. We never will know. We can’t turn the clock back, so how do we move forward?

Owning our past

Charles Reagan Wilson is retired chair of history and professor of Southern Studies at Ole Miss. In Baptized in Blood, he argues that “evangelical Protestantism lay at the heart of Southern identity and was central to Southern efforts to wage a culture war against Northern influences after the war.”

He observes:

Antebellum Southern religious leaders had emphasized the doctrine of the “spirituality of the church,” which meant that the church’s role was in religious affairs, not in political and societal matters. … While Southern religious leaders and their institutions had a sense of social responsibility, they believed in the preservation of the status quo. Social concern, in short, meant a conservative interest in the preservation of religious, political, societal and economic orthodoxy. … Ironically, the two dominant Southern denominations (Methodist and Baptist), which had begun as dissenting, non-established sects, emerged as virtually the recognized religion of the South. They learned to use the state to gain their goals.

As a result of the evangelical consensus, a lack of pluralism and diversity came to characterize the Southern religious scene. While early American churches had in general known this same evangelical union, new religious forces had entered the picture even before the Civil War, and this trend accelerated in the late 19th century. Heterogeneity characterized the Northern religious scene, but the South remained as it had been for decades.

(Citing John L. Eighmy, Wilson continues): Southern Baptists, fearing their own loss of separate status, struggled throughout the late 19th century for a distinctive identity apart from the dead slavery issue, which had been the crystallizing factor in their emergence. This fear in fact existed in the other Southern churches, and it focused especially on the North — its churches, its religious movements, its immigrants, its power in the American nation — as the underminer of Southern religious hegemony. Southerners brooded that the Civil War had unleashed powerful forces that would descend from the North, or perhaps even emerge indigenously, and destroy the Southern Zion they were building. … Southern Baptists were culturally captive, because they needed a consensus of separate values from the North in order to maintain a separate identity.

The reference to Zion reminds me of a pair of books written by Baptist historians who came to teach at Baylor.

Rufus Spain, my primary American history professor, wrote At Ease in Zion, about Southern Baptists from 1865 to 1900, as his doctoral dissertation at Vanderbilt. A generation later, Barry Hankins wrote Uneasy in Babylon, about Baptist unease in an increasingly pluralistic and secular South. The titles say it all, and both books are available on Amazon.

In my research I have read multiple observations that our Baptist doctrines such as soul competency and salvation by grace through faith emphasize the personal relationship with God, not the community.

I attended the first New Baptist Covenant meeting in Atlanta in 2008, and I remember two themes of that gathering: “Welcome the stranger,” Scripture from Genesis to Hebrews, and more startling, Jesus’ first sermon, in Luke 4:18, 19. “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor; he hath sent me to heal the broken-hearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, to preach the acceptable year of the Lord.”

Now, I was in Sunday school virtually every Sunday of my life. Until I left for college, my mother, an adult Sunday school teacher, sat by my bed every night and read and explained verses from the upcoming Sunday school lesson. And for 16 years I taught youth, which means I taught the Gospel of Luke four times — 52 weeks. And yet this was foreign to me. Even as we “surveyed the Bible,” the Sunday School Board picked the chapters and verses to be emphasized. According to Wilson, the Southern Baptist Convention went into the publishing business because it didn’t like what Northern Baptists were publishing.

What do we do about Christian nationalist friends, colleagues and family — everyone we know who complains about “erasing history” and “rewriting history”? What can we do not just to rebut but to refute the mythology?

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church

Consider the story of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond and its history and reconciliation initiative. This is from the church website:

We are part of a living and evolving history. Our story began in 1844 as the United States’ economic and political structures fully embraced racial slavery. The resources that made this church possible came directly from the profits of factories and businesses, built on the backs of enslaved African American people. During those years, many white Protestants sought to justify slavery as God’s plan. St. Paul’s members also supported, along with most proslavery Protestants, a theology that insisted that God ordained racial inequality and that, as white people, they had a responsibility to govern Black people. St. Paul’s became inextricably entwined with the Confederacy during the American Civil War. It was the home church to Confederate officials and officers and the scene of dramatic events at the end of the conflict. In the aftermath of the Civil War, St. Paul’s officially recognized its connections to Robert E. Lee, who worshipped here, and Jefferson Davis, who was baptized as a member of the parish, by marking their pews and installing windows in their honor.

Theological nostalgia for the Confederacy and its assumptions about race relations made St. Paul’s members comfortable with Jim Crow segregation in the 20th century, and its people made decisions that shaped the racial geography of the city. But our theological contexts evolved, and as an active center of social outreach in the 1920s and 1930s, St. Paul’s people engaged with African American religious leaders in unexpected ways to advocate for improved social and municipal services in African American neighborhoods. Yet Confederate symbols and ceremonies remained at home in St. Paul’s, even as St. Paul’s parishioners charted a moderate course through the Civil Rights movement in Virginia. Beginning in the 1970s, St. Paul’s undertook dozens of initiatives intended to alleviate the legacies of racism and segregation in Richmond, including the funding for public health, educational, and fair housing projects.

“In this service, we’re working on re-narrating the story we tell about ourselves.”

We are part of a living and evolving history — a journey toward becoming a beloved community in service to racial healing and justice. While our church is rooted in great injustice, our story reveals great transformation and courage among our members who we have not remembered as we do the famous war heroes. Taken together, our whole story provokes us to think about repentance. To repent is to turn around. We are turning. There is more turning yet to do. We feel our impatience, our perfectionism, our inadequacy, our clumsiness, our courage, our cowardice, our great desire to make things whole again. We humbly acknowledge that this service of remembrance and repentance is but a step along a journey. In this service, we’re working on re-narrating the story we tell about ourselves, of remembering the forgotten so that we can take the important step of telling the truth. We will need other moments of liturgy and ritual, and we will certainly need to labor on, within our walls, and with our neighbors throughout this city.

The church adopted a mission statement that says: “In light of our Christian faith, we will trace and acknowledge the racial history of St Paul’s Episcopal Church in order to repair, restore and seek reconciliation with God, each other and the broader community.”

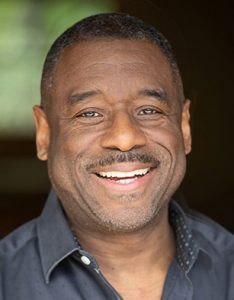

Stephen Newby

The guiding Scripture of this mission is Isaiah 58:12 — “Your ancient ruins shall be rebuilt; you shall raise up the foundations of many generations; you shall be called the repairer of the breach, the restorer of streets to live in.”

Stephen Newby, a Black musician, minister and scholar who served two years as music minister at Peachtree Presbyterian Church in Atlanta before coming to Baylor to head the Black Gospel Music Program, said to me, “Sometimes it seems like churches and people who walk the walk think they no longer need to talk the talk.”

As a church that walks the walk, what else do we need to do? How do we become repairers of the breach and restorers of streets to live in?

Ella Prichard

Ella Wall Prichard is a history and journalism graduate of Baylor University. She was a member of the Baylor Board of Regents and a director of the Baylor Alumni Association. Her book, Reclaiming Joy: A Primer for Widows, recounts the story of her husband’s untimely death and her suddenly finding herself the president of the family oil business. A longtime resident of Corpus Christi, Texas, her primary residence now is in Dallas, where she is a member of Wilshire Baptist Church. This article originated as a presentation to Compass Class at Wilshire.

Related articles:

Tearing down statues doesn’t erase history | Opinion by Ella Wall Prichard

What to do if you unearth a history of slavery in your church, college or institution?

Of statues and stories: Reckoning with the Lost Cause | Opinion by Greg Garrett

Paved A Way: Why we need to relearn the history of infrastructure | Opinion by Collin Yarbrough