There is the world the church acts like we all live in, and then there’s the world real people live in. These are not the same places.

It has taken more than a year of deconstructing my own experiences as a pastor to come to this startling realization, which few clergy will admit. And for anyone reading this who thinks I’m telling your story, be assured that’s purely coincidental; I am telling our story — our collective story.

While it is noble and even biblical for the church to hold up a standard — of how life ought to be, how people ought to behave, how families ought to function — it is not realistic to act like heaven already has come down and glory has filled everyone’s souls.

One of the greatest lessons I learned as a pastor is many families and many individuals are not who they appear to be. Christians especially are skilled at putting up a good front, despite whatever really goes on at home. A few of these facades fall more easily than others, but I’m here to tell you no pattern can be found. For every embarrassing fact that comes out, 10 more likely remain hidden.

Every Sunday, people sitting in your pews — whether real or virtual these days — are battling addictions, depression, suicidal thoughts, financial distress, impossibly broken relationships, questions about sexuality, abuse, unhappy marriages, problem children, stupid mistakes, obsessions. And the list goes on. Some of them are acting out in unhealthy ways that may remain hidden, while some are struggling more openly, whether or not anyone thinks to ask how they’re doing.

One of the myths the church perpetuates is that people with problems are “out there” and need to be brought into the church for salvation. The reality is a whole lot of people inside the church live with just as many problems as those who never darken the doors. We fervently hope those who attend church find help to address their problems, and we offer that same hope to those yet to enter the fold.

Christian churches tend to preach against the “big” sins like drug addition, sexual infidelity, gambling, pornography and such, while acting like a whole range of other behavioral problems don’t exist.

Christian churches tend to preach against the “big” sins like drug addition, sexual infidelity, gambling, pornography and such, while acting like a whole range of other behavioral problems don’t exist. The reality is all these things exist, and church is the last place anyone wants to talk about them.

In fact, people often go to extreme lengths to avoid talking about them. For example, while churches prudently and necessarily run criminal background checks on volunteers, shame prevents some church members from volunteering. They don’t want anyone at church to know what’s on their criminal records at some point in the past — maybe a DUI while in college, a drug bust or a financial failure. While these are not typically the behaviors churches try to weed out among volunteers, some people fear they will get caught in the dragnet and experience shame among their peers.

Even as common as divorce is today, I know several former active church members who are so embarrassed by their “failed marriages” — a horrible term, by the way — they cannot bear to return to church. Or if they do, they slip in and sit on the back row.

Even as common as divorce is today, I know several former active church members who are so embarrassed by their “failed marriages” — a horrible term, by the way — they cannot bear to return to church. Or if they do, they slip in and sit on the back row.

Drug and alcohol additions get a lot of publicity, but these are not the only — and perhaps not even the most common — addictions. Large numbers of people inside and outside the church live with food addictions, sex addictions, exercise addictions, gambling addictions, Internet addictions, gaming addictions, shopping addictions and more. These are the less-talked-about but equally shame-filled behaviors common to real life.

Here’s another truth: Those who struggle often are more in touch with reality than church leaders living on a cloud.

And, by the way, the pandemic has made all addictive behaviors worse, just as it has added to financial distress, depression and everything else that plagues the human condition. The pandemic has been an accelerant like nothing we’ve seen in our lifetimes.

Here’s another truth: Those who struggle often are more in touch with reality than church leaders living on a cloud.

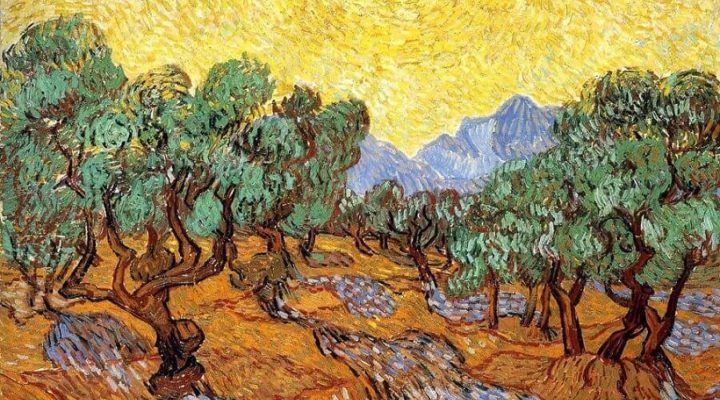

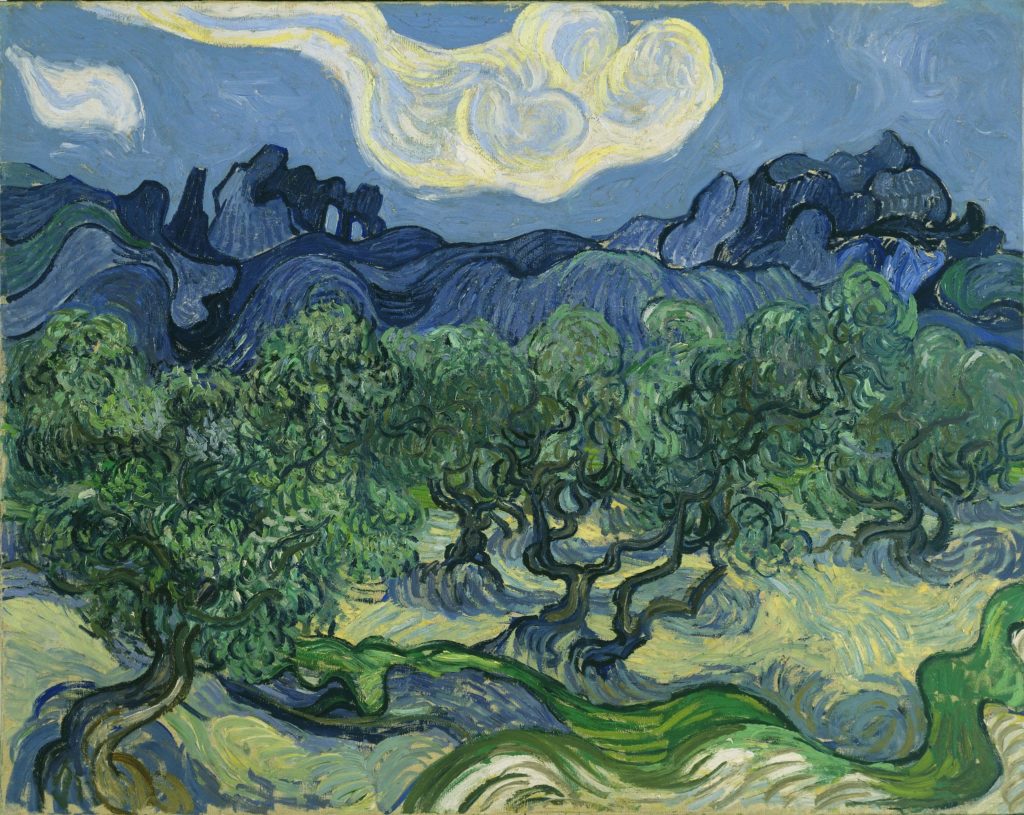

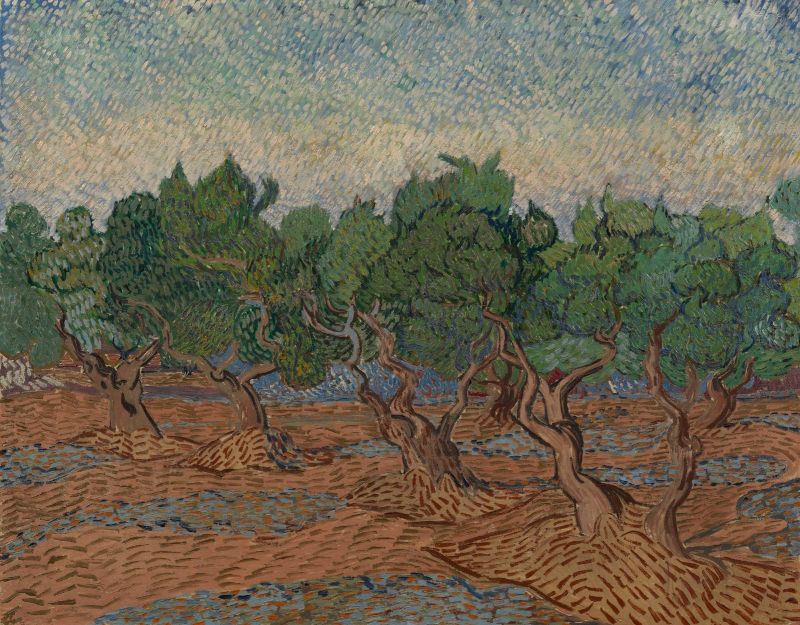

In May 1889, the artist Vincent Van Gogh checked himself into an asylum in France, fearful he was headed for yet another mental breakdown. The asylum was located in the Chaîne des Alpilles mountains, near the Mediterranean coast. Ironically, it was located in a former monastery.

While there, he painted 150 canvasses, including a series of wheat fields and olive trees within view of the asylum. In his depression, he painted vibrant colors and abstract swirls. (If you’ve ever seen van Gogh’s “Starry Night,” think of that but as a landscape.)

Curators of an exhibit currently on display at the Dallas Museum of Art explain in Van Gogh’s art, olive trees symbolize biblical and spiritual life found in the Bible’s narratives.

A few weeks later, after Van Gogh fell into another series of breakdowns, two artist friends — Emile Bernard and Paul Gauguin — sent Van Gogh copies of their current works illustrating the biblical story of Christ praying in the Garden of Gethsemane on the night of his betrayal. Gauguin, an arrogant sort, placed his own face on the Christ figure praying in “Christ on the Mount of Olives.” Van Gogh did not approve.

Bernard sent a letter and a photograph of his own new painting of Christ in the Garden of Olives. Van Gogh responded, begging him to do better, calling the painting by his young friend “atrocious.”

The museum curators explain Van Gogh did not like what his friends had painted, believing their renditions were too imaginative and not based in a close study of real olive trees. Van Gogh’s responses to Bernard and Gauguin indicated he would rather paint the real olive trees outside his window than the imaginary garden of Christ’s agony. In Van Gogh’s mind, reality was the source of strength.

Even though Van Gogh had been influenced by the Impressionists, he carefully studied the real-life basis of what he painted. Thus, one commentator described his olive tree painting as “rendered as gnarled and arthritic as if a personification of the natural world.”

Raised in the church and deeply influenced by faith, Van Gogh firmly grasped the reality of his deteriorating mental state. Consequently, he had no interest in a sanitized or even personalized depiction of the biblical narrative. He needed help right then, as he struggled to stay alive day after day.

What’s the answer to all this? I don’t know. But I do know this is a time when the questions may be more important than the answers. What are we preaching? What are we teaching? And how connected to reality does it sound?

What the church somehow needs to do is to acknowledge with gut-level honesty the reality of where we live and how we live.

While some truly awful people exist in this world, many more good people do things they shouldn’t, think things they wish they didn’t, and succumb to all the temptations common to humankind. The real world is not made up of “good” people and “bad” people.

I am not suggesting churches start 15 kinds of support groups. Most people are not going to air their dirty laundry at church, no matter how confidential you promise to be. Nor am I suggesting a 10-week sermon series on living a godlier life. We’ve heard that before, and it didn’t take.

What the church somehow needs to do is to acknowledge with gut-level honesty the reality of where we live and how we live. We need to offer tools to talk about this reality within our families, within our networks and among our friends. The church somehow needs to paint more like Van Gogh and less like Gauguin.

Mark Wingfield serves as executive director and publisher of Baptist News Global.

Related articles:

For clergy, it’s unsettling to realize sometimes the helper needs help, / Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Face up to these five realities of church life today / Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Longitudinal study of 50 clergy approaches the 10-year mark

Four viruses of the pre-COVID church and their vaccines / Opinion by Mark Tidsworth