In July 2025 we will mark the 100th anniversary of the Scopes trial regarding the teaching of evolution in Tennessee. The trial represents a key moment in the debate between modernists and fundamentalists.

Like all history, the story offers insights for today. However, part of the story was buried for decades in the archives of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky. — promptly to be buried again by this author, who was a seminary student too caught up in other projects to pursue publishing what I found.

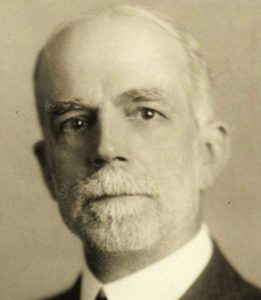

The discovery happened because of an assignment in Charles Scalise’s church history class. We were to write a paper comparing two figures from church history. Immediately after receiving the assignment, I found myself sitting in the seminary’s Broadus Lounge. On the wall beside me was a portrait of E.Y. Mullins and a plate that said he was president from 1899 to 1928. I immediately wondered if William Jennings Bryan would have invited Southern Baptists’ preeminent leader to testify as an expert witness on behalf of the prosecution at the 1925 Scopes trial.

Setting the stage

American teacher John Thomas Scopes (1900 – 1970) (second from left) standing in the courtroom during his trial for teaching Darwin’s Theory of Evolution in his high school science class, Dayton, Tennessee, 1925. Scopes’s case came to be known nationwide as the ‘Scopes Monkey Trial.’ (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Tennessee had passed a law banning the teaching of evolution. The stage play and subsequent feature film Inherit the Wind take many dramatic liberties with what transpired, while capturing the essence of the events. For one thing, high school biology teacher John Scopes never was handcuffed and carted off to jail. Multiple forces — especially the American Civil Liberties Union — just wanted to stage a trial to test the law.

When I served as an associate pastor in Knoxville, Tenn., one of my congregants was the late Mildred Knight Cockrum (wife of the late Howard Cockrum, who was at the time the last layperson to chair what is now Southern Baptist’s North American Mission Board). Mildred told me her father, Floyd Knight, was a judge in the Dayton area and that he told her the trial was concocted by local business owners to get tourists to come to town. If that was the plan, it worked. Tiny Dayton, Tenn., became packed with thousands of people who came to see the trial in the hot Southern summer of 1925.

The masses arrived, in part, because the organizers deftly invited lightning-rod attorneys for both sides. Representing the defendant was Clarence Darrow, identified as an infamous liberal for opposing the death penalty and the United States’ annexation of the Philippines.

The prosecution was conducted by William Jennings Bryan, three-time Democrat nominee for president and whose “Cross of Gold” speech is considered one of the most noteworthy examples of American oratory.

Bryan and the Wizard of Oz

According to Robert Devine in America Past and Present, Frank Baum’s 1900 novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was political allegory about the U.S. economic controversy. Some wanted to maintain the gold standard — seen to favor the wealthy; others favored switching to a two-metal gold/silver standard using greenback — seen to favor the poor and middle class. Dorothy represented common Americans. Her silver slippers treading on yellow bricks represented the proper balance on the way to the land of emerald (green dollar bills). Tin Man represented industry; Scarecrow was agriculture, and Cowardly Lion represented William Jennings Bryan and his followers who needed the courage to promote their cause in the face of the elite forces arrayed against them.

Scene from the film version of “The Wizard of Oz.”

Thus, the Everyman and Everywoman of Tennessee would have seen the deeply religious Bryan as their champion. While Inherit the Wind portrays Bryan as something of a buffoon, and say what you will about his dogma, he was concerned that Darwinian evolution’s tenants might be used as a rationale for the elite to dispose of those they saw as a threat to the survival of the fittest. Thus, even if tyrants existed prior to the theory of evolution, Bryan anticipated a survival-of-the-fittest ideology would give way to an oppressive regime.

Seeking expert testimony

The subsequent rise of Nazism, with its sense of brute superiority, demonstrates at least Bryan’s awareness of the abuse of the theory of evolution, even if his atheistic opponents might use his same argument to argue against theism, religions of which have prosecuted many holy wars. With his sincere fear of evolution being taught coupled with general passion to win the case, Bryan would have wanted to infuse his case with expert testimony.

Which is why as I sat in that seminary lounge in the spring of 1991, I wondered if Bryan tried to tap E.Y. Mullins as a prosecution witness at the Scopes trial.

I went to the seminary archives to see if I could find out. After all, one day I had found a cabinet unlocked in the Billy Graham Room, and I had leafed through telegrams to Billy Graham. I found one that congratulated Graham on a recent crusade — I think in New York — and said something like “Thank you for your kind words about my movie on the commandments.” – Cecil B. DeMille.

Treasures abound in archives. What might I find about William Jennings Bryan and E.Y. Mullins?

I asked a librarian who told me all of President Mullins’ correspondence was indexed in a bound volume in the stacks. I found the volume. The correspondence was organized in chronological order by date. I estimated an invitation from Bryan would have come within six months of the trial that was in July 1925. I started scanning from January.

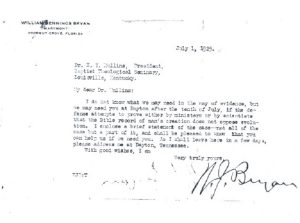

Suddenly, under July 1, 1925, I saw “Bryan, W. J.” My heart accelerated. I raced to the vertical file cabinets. There was a thick folder for each month. I took July 1925 to a table and began delicately turning page after page. I saw a letter from a prospective student asking President Mullins for help securing employment in Louisville. I kept turning pages. Then, there it was — on stationary from William Jennings Bryan’s Coconut Grove, Fla., estate.

All of what follows has now been transferred to microfilm. Here is the text in which Bryan presumptively asked Mullins to testify on behalf of the prosecution:

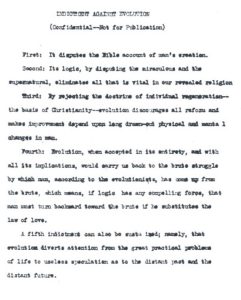

Attached to the letter was a document with the outline of what Bryan anticipated to be his main arguments. It is titled “INDICTMENT AGAINST EVOLUTION (Confidential—Not for Publication.)” The context of the confidentiality was not to let the defense know his strategy. Due to that context no longer being pertinent and the fact that 97 years surely exceeds the limitations of an expectation of confidentiality on something of this nature, it seems appropriate to publish this historically significant document. Bryan said:

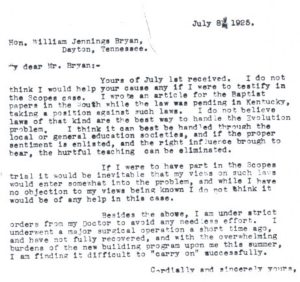

Attached to this was a mimeographed copy of Mullins’ reply, dated July 8, 1925, and addressed to “Hon. William Jennings Bryan, Dayton, Tennessee.

Was Mullins modeling a third way?

Given Mullins’ health concerns, it seems noteworthy that he bothered to send more than the last paragraph, starting with “I am under strict orders.” He took the time to directly challenge Bryan. While Mullins saw evolution as a “problem,” he also saw laws suppressing its teaching as a problem.

In the mid to late 1990s, after reading an article by current Southern Baptist Theological Seminary president Albert Mohler addressing Mullins’ stance on evolution, I wrote Mohler, informing him of the correspondence I found between Bryan and Mullins. Mohler wrote me back stating that Mullins’ objection to laws against teaching evolution notwithstanding, it was clear that Mullins was not an evolutionist.

In looking to see if anyone else had ever found and published the correspondence, I found that Mohler published a 2009 essay on Mullins. He cites William Ellis’ book A Man of Books and a Man of the People: E.Y. Mullins and the Crisis of Moderate Baptist Leadership as reporting that Mullins not only declined an invitation to testify for the prosecution of Scopes, he also declined from the Darrow camp to testify for the defense.

E.Y. Mullins

When I was in the Mullins archives back in the early 1990s, excited by my discovery of the correspondence between Bryan and Mullins and by Mullins’ reference to his article opposing laws, I dived deeper into the archives. I found Mullins’ hand-written manuscript of the article he referenced. I checked out several book in the Southern Seminary library on the subject of evolution.

At one point in one very old book I found, underlined in pencil, a passage that expressed an idea that seemed nascent to a statement Mullins made in his article. I wondered if I could find out if Mullins had checked out this book. I flipped to the back cover to see if the checkout card might have his name. The checkout card had been removed when that system was phased out. But when I flipped to the front cover, there in the same shade of pencil as the underlining was the cursive signature of E.Y. Mullins. He had owned the book, and I could see the interaction between Mullins’ thought and the author’s.

My notes have been lost, but I contacted the Southern Seminary library and based on my description, examples of such books were found in their archived Founders Books collection. The book may have been Evolution and Christianity by James Iverach, Evolution and the Christian Faith by Henry Higgins Lane, or one of several other of Mullins’ books.

A parable

Meanwhile, back in the Mullins archives of the early 1990s, I found a handwritten document titled “The Parable of the Mice and the Piano.” In the process of writing this article, I performed an internet search to see if the parable ever had been published. I found three versions, all of which attributed the parable to the London Observer but without a date. I have not been able to locate the original version. Apparently, the exact source escaped Mullins too. My search also led me to his 1926 sermon “Faith and Science,” in which he referenced the parable. Mullins said:

I have read somewhere a parable of the mice inside a piano listening to the sounds as the piano was played. They put down their scientific explanation: First the impact of keys upon cords. Second, the vibrations which followed. Third, the sounds and the music which followed the vibrations. Impact, vibration, sound; many impacts, many vibrations, many sounds, this was the formula of the mice. There was nothing else. This is the way in which a piano behaves of itself. The mice saw no one. They were confined within. They needed no other explanation.

But do you not see that the mice have not explained at all? They have only described what they heard. They had the bare facts. But the facts needed interpreting. What did they mean? The interpreter would point to the player at the keyboard of the piano, the musical composition, the skill, the music. So the universe must be described as science describes it. But it must be interpreted as religion interprets it. The two methods are different. But both science and religion seek reality. Both work by faith and both attain real knowledge.

“Arguably, Mullins saw the Scopes trial as pitting science and religion against one another, and he wanted no part of it.”

Mullins’ use of this parable reveals a view of religion and science working together. Arguably, Mullins saw the Scopes trial as pitting science and religion against one another, and he wanted no part of it. Mohler stated, “That both Bryan and (Darrow) thought Mullins could be of assistance indicates the opaqueness of Mullins’ position.”

While Mullins’ intellectually evolving position on biological evolution was not crystal clear, the invitation by both prosecution and defense at the Scopes trial is more likely a function of the defense team — advised by a friend of Mullins — being aware of Mullins’ writings opposing laws restricting the teaching of evolution. Bryan’s letter, on the other hand, makes it fairly clear he was unaware of Mullins’ opposition to such laws. It’s not like Bryan could Google “Mullins evolution controversy.” He likely was just assuming Mullins would be in lock step with Bryan’s own position.

Lessons still to learn

A century later, we have much to interpret and learn from the Scopes trial and from Mullins’ opaqueness as he navigated the most daunting controversy of the early 20th century. Detractors might say he was dodging controversy; admirers might see him following the biblical injunction to be as gentle as a dove but as shrewd as a serpent.

Clarence Darrow, left, and William Jennings Bryan speak with each other during the Scopes trial in Dayton, Tenn., in 1925. (AP Photo, File)

Not allowed to call expert witnesses, Clarence Darrow put Bryan on the stand and eviscerated his literalist interpretation of Scripture. While Scopes was found guilty of teaching evolution, he was given a largely symbolic fine of just $100. Bryan died three days after the trial, where he was not allowed to give his final speech.

While the left likes to impugn Bryan as a dogmatic windbag, he deserves much credit for championing the underclass and for anticipating the problems of socialized Darwinism. While the right often still impugns science, few decline the benefits of modern medicine such as MRIs or COVID vaccines.

Oh, wait.

The left looks at the right’s stubborn resistance to the new and courageously calls for change on behalf of common people whom they would never disparage as a “basket of deplorables.”

Oh, wait.

Maybe we would all do well to learn from the best of Mullins and Bryan. What Mohler rightly called Mullins’ opaqueness put Mullins in the position — as described by Glenn Hinson — to convince Southern Baptists not to insert an anti-evolution phrase into their 1925 belief statement. Mullins strived to keep the focus on faith rather than politics.

Conversely, historian Hal Williams asserted that Bryan’s populist economic agenda laid the groundwork for Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal that ushered the U.S. through the Great Depression. It’s easy to allow Bryan’s theological fundamentalism to distract from his compassionate economics.

Return to the parable

Maybe the right and left need to look at Mullins and Bryan in opposite directions than their reflex. While Mullins used “The Parable of the Mice and the Piano” to argue for the existence of God, maybe the right is stuck outside the piano — focused on the Creator — and needs to venture into the piano to revel in the creative methods that may be more complex than any book — even sacred Scripture — can fully capture.

“Both left and right in contemporary theo-political debates seem to treat each other with disdain rather than as fellow pilgrims on a road fraught with dangers.”

Meanwhile, Frank Baum’s parable The Wonderful Wizard of Oz depicted Bryan as a cowardly lion who was quite courageous after all. Maybe the left doesn’t need courage so much as it needs humility to look upon the hurting not as a “basket of deplorables.” Both left and right in contemporary theo-political debates seem to treat each other with disdain rather than as fellow pilgrims on a road fraught with dangers. Maybe these dangers are best faced with mutual cooperation that is nurtured not by disdain but compassion.

It bears pointing out that Frank Baum, creator of one of America’s most beloved stories, was a rabid racist who twice, in writing, explicitly and viciously called for the genocide of Native Americans. Baum missed a key point of his own story because he didn’t see Native Americans as fellow humans sharing life’s journey.

We need to remember to reflect deeply on our own stories and how our beliefs may not be internally consistent or justly applied. William Jennings Bryan and E.Y. Mullins both were persons of sincere faith who with great passion and intellect spoke up for common folk and common decency. As we approach the centennial of the Scopes trial, we would be well advised to reflect on piano mice, cowardly lions and how to be the best of both: humble seekers of the supreme that is beyond us and the nobility that is within us.

Brad Bull is a private practice family therapist in Tennessee. He holds a master of divinity degree with a major in pastoral counseling and a Ph.D. in human ecology. He has served as an associate pastor, university professor and UPS driver helper. His memoir on his early years in ministry is titled Restacking Caps and Loving the Monkeys Who Took Them — Blunders, Conflicts, and Redemption is the Early Journey of a Peddler of Soul Mending.

Related articles:

The Scopes Trial, then and now | Opinion by Bill Leonard

The Maus saga: A case study of our present crises | Opinion by Bill Leonard