The folks at Palmetto Missionary Baptist Church in Conway, S.C., were ready for just about anything Hurricane Isaias had to throw at them.

“We’re so seasoned with hurricanes and tropical storms that most people pretty much stay ready,” Senior Pastor Cheryl Adamson said of the congregation and city located roughly 14 miles from the Atlantic Ocean and 43 miles from where the storm came ashore in North Carolina late Monday, Aug. 3.

Cheryl Adamson

“No special preparations were made, especially because it was going to be a tropical storm or a Category 1,” she explained.

Isaias became a hurricane just before coming ashore at Ocean Isle Beach, N.C., located just north of the state line. It brought flooding, power outages and some house fires to some areas.

The Cooperative Baptist Fellowship of South Carolina tracked the storm throughout the day on Monday, Aug. 3, and identified five partner churches — including Adamson’s — that were closest to Isaias’ path, Coordinator Jay Kieve said.

None of them reported damage, but all stood ready to respond in their communities if needed.

These communities “have suffered flooding from hurricanes several times in the last few years,” Kieve said. “These are resilient and caring communities with faithful churches who will help their communities pull together for recovery if necessary.”

Damage was more severe in parts of North Carolina, where spin-off twisters, flooding and at least two deaths were reported, according to media reports. CBF North Carolina Executive Coordinator Larry Hovis reported no significant damage to any of its partner congregations.

Jay Kieve

Destructive winds and extreme flooding weren’t the only impacts North and South Carolinians avoided due to Isaias’ relatively light punch. They also were spared learning how much the COVID-19 pandemic might have complicated response and recovery efforts.

Residents of Mexico and the United States have experienced that difficult lesson in the aftermath of Hurricane Hanna, which made landfall south of Corpus Christi, Texas, on July 25. It brought mass flooding to the border region. Some faith-based aid agencies were unable to send volunteers due to concerns about coronavirus outbreaks.

In South Carolina, Adamson said she heard that some shelters were prepared not to operate in the usual manner and that hotel room vouchers were being considered as an alternative.

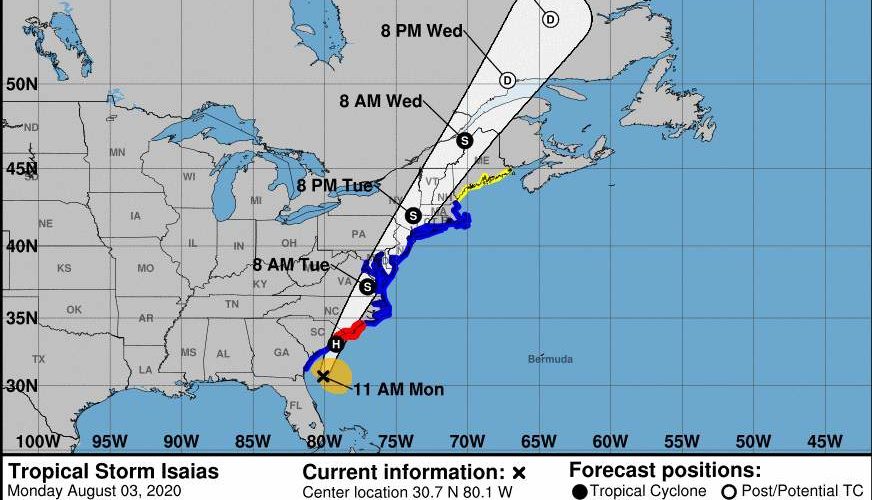

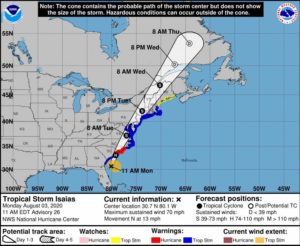

Hurricane Isaias (Image/National Hurricane Center)

Such uncertainties are shared by communities around the world, said Eddy Ruble, CBF’s international disaster response coordinator.

The coronavirus worsens the impact of other natural disasters partly because the movement of material aid and volunteers are impeded by the pandemic, he said. “Internationally, travel is virtually at a stand-still. One must have a pre-approved visa, a negative COVID-19 test, and then mandated 14-day hotel quarantine in most countries if one is allowed to enter at all.”

These requirements effectively eliminate the possibility of proving in-person disaster assistance from one nation or region to another, he said. “This gives greater emphasis on relying on national partners to respond to disasters domestically.”

Eddy Ruble

The pandemic itself is a form of natural disaster because it is creating both health and economic hardships, especially for the poor and those whose jobs cannot be performed remotely, Ruble explained. “As the pandemic stretches into months and perhaps years, the cumulative impact will become more pronounced — especially among the poor, day labors and migrant workers.”

But it may also be tearing down national and global economies, he said. “I see COVID-19 as a slow-onset disaster — much like a drought or famine. The conditions are present for impending greater disaster if there is not a medical solution or a major restructuring of government spending and economic assistance.”