Religious leaders must learn to embrace new ways of relating to the mental health and spiritual challenges of young people or risk contributing to their continued alienation from faith institutions, the coordinator of a new national study says.

Josh Packard is a sociologist of religion who leads Springtide Research Institute, which specializes in understanding 13- to 25-year-olds. The organization just released its latest annual study on the religious and emotional needs of Generation Z.

While the COVID-19 pandemic severely accelerated the mental health crisis 13- to 25-year-olds already were facing, the problem has been further exacerbated by ministers and other adults who underestimate or stigmatize their emotional suffering, Packard warned.

While the COVID-19 pandemic severely accelerated the mental health crisis 13- to 25-year-olds already were facing, the problem has been further exacerbated by ministers and other adults who underestimate or stigmatize their emotional suffering, Packard warned.

“If religious organizations, religious leaders and spiritual leaders do not respond effectively, then we’re going to miss a real opportunity here to help young people flourish in all parts of their lives,” he said during the Oct. 19 webinar release of “The State of Religion and Young People 2022: Mental Health — What Faith Leaders Need to Know.”

The 104-page report is based on a survey of 10,000 people between the ages of 13 and 25 about their religious beliefs, practices and attendance habits, and about the quality of their relationships with adults and peers. More than 100 additional young people participated in in-depth interviews.

The project confirmed other experts’ observations that young people are experiencing the biggest mental health crisis ever recorded.

The big mental health crisis

The project confirmed other experts’ observations that young people are experiencing the biggest mental health crisis ever recorded, the report states. “The American Academy of Pediatrics, the Children’s Hospital Association, and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry have declared the mental health crisis among young people in the United States a national emergency. Our data reflect this urgency.”

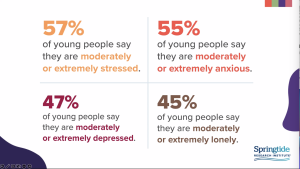

Almost half those surveyed (47%) said they were moderately or severely depressed. More than half (55%) reported being moderately or severely anxious while 57% expressed moderate to severe levels of stress.

Almost half those surveyed (47%) said they were moderately or severely depressed. More than half (55%) reported being moderately or severely anxious while 57% expressed moderate to severe levels of stress.

The reports adds: “Forty-five percent report being moderately or extremely lonely. Sadly, the majority of young people (61%) agree with the statement, ‘The adults in my life don’t truly know how much I am struggling with my mental health.’”

But even when adults are aware of those experiences, they often do not take them seriously, Packard said. “A lot of times adults dismiss what young people are calling ‘trauma’ and ‘sadness’ and ‘hardship’ in their lives. … And young people tell us that when that happens to them, they just lose so much trust and respect for the adults who are making those claims.”

Trust also is eroded when adults clearly have a negative view of mental health challenges, he said. Aware of that stigma, young people often feel safe speaking only with peers about their struggles.

“They’re relatively comfortable with this conversation with each other, but they know that it weirds out the adults in their lives to be having these kinds of talks,” Packard said.

They know when adults are afraid

Gen Z youth and adults also sense when adults are simply afraid of the topic, said Marte Aboagye, head of community engagement for Springtide.

Young people routinely share this fact with the organization through its ambassador program, social media and podcasts, she said. “What they are repeatedly telling us is that while they want to talk to the trusted adults in their lives about their mental health experiences, they sense that those adults have some trepidation to actually have these conversations, that adults don’t always feel comfortable. So, they talk more to their peers.”

Young people routinely share this fact with the organization through its ambassador program, social media and podcasts, she said. “What they are repeatedly telling us is that while they want to talk to the trusted adults in their lives about their mental health experiences, they sense that those adults have some trepidation to actually have these conversations, that adults don’t always feel comfortable. So, they talk more to their peers.”

Aboagye presented several short videos of young people expressing those concerns, including a teen who wished adults would understand it’s OK for her to be sad without a reason, and another saying it doesn’t require a crisis to need help.

Such missteps by religious leaders represent lost opportunities for relevancy, compassion and helpfulness, Packard added. “A lot of the people who might have been well positioned to support (young people) through the lens of faith and religion are not necessarily super-connected to them anymore.”

Spiritual connection

Understanding Gen Z faith and spirituality is another key to effectively ministering to young people in this moment of emotional crisis, Packard said.

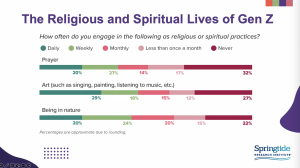

The report found that 51% of those surveyed said they developed a prayer practice during the pandemic, and 45% said they started practicing meditation. Reading (42%), being in nature (32%), and yoga and the arts (31%) also were cited as ways of coping.

The report found that 51% of those surveyed said they developed a prayer practice during the pandemic, and 45% said they started practicing meditation. Reading (42%), being in nature (32%), and yoga and the arts (31%) also were cited as ways of coping.

“A majority of young people who say they are religious agree that their religious or spiritual life matters to their mental health (66%),” the report explains. “Nearly three-quarters (73%) agree with the statement, ‘My religious/spiritual practices positively impact my mental health.’”

Those statistics indicate there may be room for traditional religious institutions and practices in some young people’s lives.

But Packard added that the numbers also reveal that faith groups must be flexible when reaching out to Gen Z: “A number of young people think of acts of protest as religious and spiritual practices, so they’re engaging and exploring the contours and boundaries of what religion and spirituality look like.”

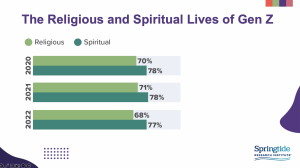

The survey confirmed that a majority of young people consider themselves to be spiritual or religious, but in diverse ways.

The survey confirmed that a majority of young people consider themselves to be spiritual or religious, but in diverse ways.

“About one-third of young people claim to be ‘just Christian,’ ‘nothing in particular,’ or ‘agnostic,’ and more than 60% of young people agree with elements of multiple religions. Regardless of affiliation, those who claim to be either religious or spiritual report higher levels of flourishing,” the study said.

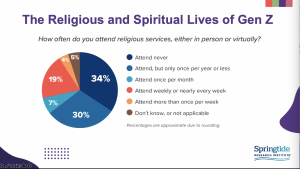

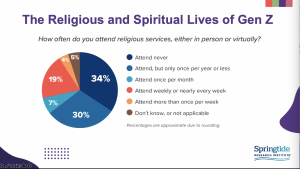

But for 34% of young people, those practices do not include attending virtual or in-person services, while 30% said they attend once a year or less, and 19% attend weekly or nearly weekly. Only 4% said they attend more than once a week.

But those who are part of a spiritual community claimed higher levels of flourishing, the report said. “Those who report currently being connected to a religious or spiritual community claim greater mental and emotional health than those with only a prior connect and those who never had such a connection.”

Build relationships

Packard said the statistics should convince faith groups they can help young adults by building relationships with them — as long as they can be flexible.

Josh Packard

“A lot of times young people don’t feel like they have any relationships. Something like a third of young people have one or fewer trusted adults in their lives,” he said. “So, creating more belonging inside our organizations with young people really starts to fill this gap. … These connections are absolutely vital for young folks so that they don’t feel like they’re going through these struggles alone.”

Religious leaders should create plans for how to reach out to young people who are overwhelmed or withdrawn, he said. “Of course, all of this is predicated upon the idea that you know young people well enough to know when they are not being themselves.”

Helping young people through mental health challenges doesn’t require ministers to have all the answers, he said. “But seeking answers and leaning into mystery can be holy activities for young people, especially as they navigate some of life’s biggest questions. In fact, this is a generation that is more skeptical if they see a completely packaged answer being offered to them.”

Packard said a young person recently relayed to him what it was like to get a pat answer to a request to discuss mental health with a minister. “‘I was told to pray about it. But that didn’t solve anything. When that didn’t work, I thought, well, not only does my mental health suck but my faith life sucks too.’”

The result of such actions is a divide between the church and young people, he said. “They are often disconnected from the structures that might have automatically helped them to discover a sense of purpose in their lives.”

Helping Gen Z through its mental health and spiritual struggles can be done without watering down traditional practices and beliefs, Packard added. But it does require dedication to providing places of connection in which expectations match reality and where young people can find guidance.

“We can be there to support them, and we can be there in a way that reflects the values and and learnings of our own faith traditions and bring those things into concert with one another,” he said. “We’re seeing not so much that religion doesn’t matter to (Gen Z). It’s that they don’t see those places, and they don’t see those people, as helping them discover their sense of purpose in life.”

Related articles:

What absurdism and a parody conspiracy theory tell us about why Gen Z is sleeping in on Sundays | Analysis by Laura Ellis

Gen Z non-Christians pay most attention to those who live out their faith rather than preach it