The ethical issues surrounding development of a COVID-19 vaccine are complex but pale in comparison to the deaths that would be necessary to reach so-called “herd immunity” in the United States.

Questions get raised about the feared use of fetal tissue from abortions or leftover in vitro embryos, and about the unethical appropriation of cells from medical experimentation on Black people.

However, ethicists say none of those reasons alone should prevent the development and wide implementation of a vaccine; stopping this deadly disease is of utmost importance, and relying on so-called “herd immunity” rather than a vaccine would be a profoundly deadly — and unethical — option.

With more than 100 possible vaccines in development, a variety of methods are being employed.

How vaccines are made

“There’s more than one avenue toward the creation of vaccines,” according to Sondra Wheeler, professor of Christian ethics at Wesley Theological Seminary and an internationally known expert on theological bioethics. “There’s the time-honored one of using an attenuated or incapacitated virus itself and injecting that into a healthy person to stimulate the production of Santibodies.” That’s how the first vaccine, for smallpox, was developed.

Sondra Wheeler

A second modern path toward vaccine development is to examine the genetic makeup of an invasive organism, extract parts of it and “teach” antibodies and T-cells to “recognize” one of the proteins that appears in the virus. This, in turn, will tell the body how to respond if it encounters the virus in question.

“More and more, that’s what we do,” Wheeler said. “We don’t use whole or weakened virus anymore because there are risks involved in that. If you can trigger a response without using a real virus, that’s safer.”

Nevertheless, some coronavirus vaccines currently under development do use the attenuated live virus, as reported by Science News.

A third way toward vaccine development is to interrupt viral replication. “Remember that viruses are not technically alive,” Wheeler said. “A virus doesn’t have the capacity for reproduction.”

Instead, viruses invade by hitching rides on other living cells that do replicate. Viruses like COVID-19 use “hooks” to penetrate cell walls and hijack those cells’ reproductive processes.

“You don’t’ have to ‘kill’ the virus,” she said. “You only have to injure its capacity for successfully invading and taking over a living cell.”

About cell lines

Vaccine development and testing — like so much of medical research — often relies on human cell lines as well as cell lines from other animals. This is where ethical concerns — and misunderstandings — begin to emerge.

Anti-abortionists and particularly the Roman Catholic Church continuously raise objection to medical research conducted with fetal tissue or unused in vitro embryos. The concern is that acquisition of such tissue amounts to endorsement or encouragement of abortion, which is considered by anti-abortionists to be murder. There’s a separate yet related debate over cells created through in vitro fertilization and whether they are ethically the same as aborted cells.

These ethically questionable cells are not the cell lines required for research and testing of vaccines, Wheeler explained.

“I am not aware of any use of tissue from fetal remains after abortion in the development of vaccines.”

“I am not aware of any use of tissue from fetal remains after abortion in the development of vaccines,” she said. “Nor has it continued to be necessary to use human embryos to get totipotent stem cells: we can use sources like blood from the umbilical cord or other somatic cells and trigger cells to de-differentiate (return to an earlier form) and get human stem cells that way with no ethical problems.”

About HeLa cells

Another variety of cell line used in medical research, though, carries a different ethical dilemma. This concern is well documented in the bestselling book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

Henrietta Lacks

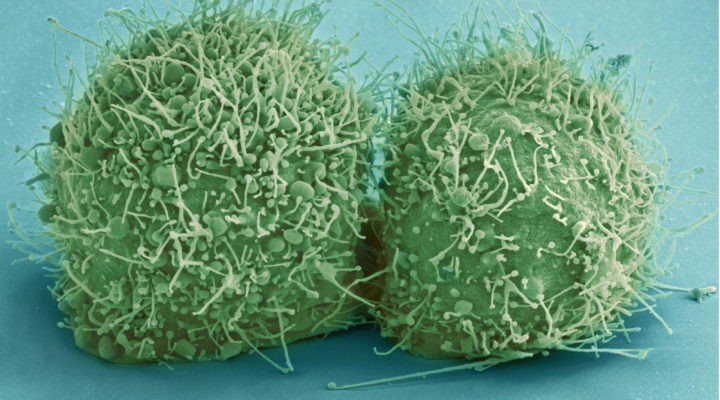

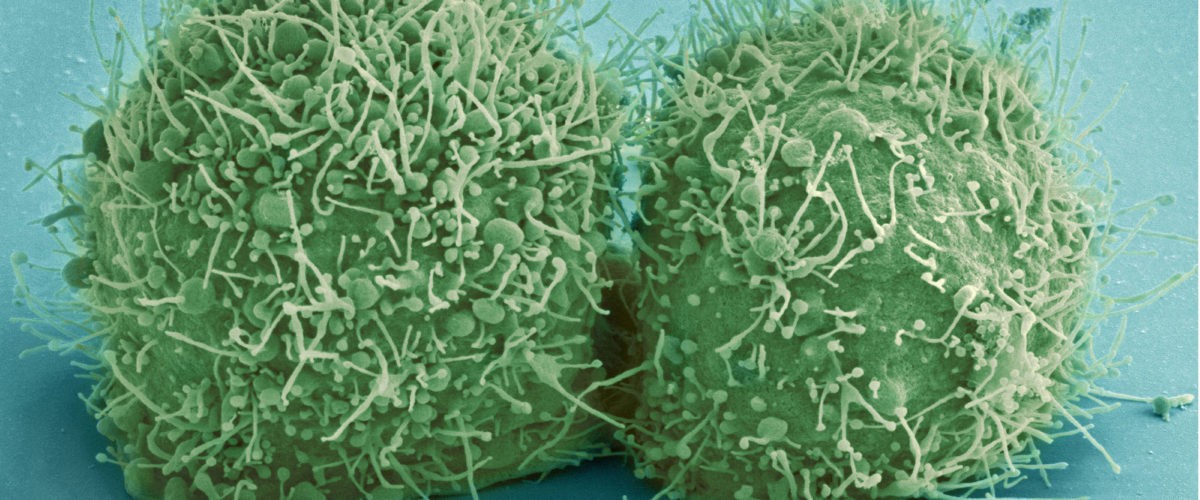

Lacks died of cervical cancer on Oct. 4, 1951, as a 31-year-old Black mother of five children. During her treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, doctors took cells from her cervix and cervical tumors without her knowledge or consent — common practice at the time — and used them in research. Her cells were found to be unusually durable and prolific, which made them ideal for use in scientific study. Most cells lines die out after a period of time and a number of replications, but “immortal” cells like hers do not.

That cell line, named HeLa by taking the first letters of her first and last name, remains the oldest and most commonly used human cell line in medical research and was instrumental in creating the polio vaccine, for example. But it was acquired through what today would be considered unethical means, with no consent and no remuneration to Lacks’ family.

American medical research has a long history of mistreatment of Black patients, most notably evidenced in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Amid the many ethical concerns of such practices, pharmaceutical companies have earned billions of dollars in profit made possible by Black citizens who received no compensation.

Approaches to COVID-19 vaccines

Worldwide, more than 100 possible vaccines for COVID-19 are in some stage of development. According to a detailed analysis in Science News, “those vaccines can be divided into a few different types.”

Some do not require the use of live cells in their production. For example, the much-discussed vaccine being developed by Moderna is an RNA vaccine, the second type of vaccine described by Wheeler. It would genetically target other cells in the body to produce antigens themselves.

There are pros to this method, including being faster and more easily produced, and cons, including the risk of unintended effects, effectiveness of delivery inside the body and a logistical challenge: Many RNA vaccines must be kept frozen or refrigerated until administered.

Other COVID vaccines in development do use live cells in their production. That would include the first and third options described by Wheeler.

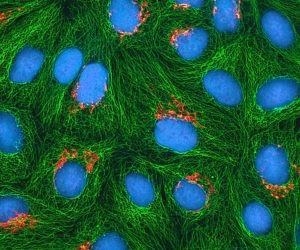

Multiphoton fluorescence image of cultured HeLa cells with a fluorescent protein targeted to the Golgi apparatus (orange), microtubules (green) and counterstained for DNA (cyan).

Some vaccines — such as those for influenza, hepatitis B and HPV — may be grown in nonhuman cell lines or chicken eggs, bacteria or yeast. But when developing new vaccines, human cell lines are the preferred option.

In the search for a COVID-19 vaccine, there’s no avoiding immortal cell lines, virologist Angela Rasmussen of Columbia University told Science News. “Certainly I would expect they would be involved in some of the work, directly or not.”

Yolonda Wilson, a bioethicist at Howard University in Washington, D.C., told Science News there could be a bit of restorative justice done especially if the HeLa cells make a COVID-19 vaccine possible.

Given the disproportionate effects of the virus among Black and Latino people in the United States, for the stolen cells of a Black tobacco farmer to offer life-saving medicine would be redemptive.

She believes that means “special effort should be made to ensure that Black people are vaccinated once we know that this is safe.”

This takes time

Whatever method is used, vaccine development and testing takes time and cannot be rushed without compromising safety, Wheeler explained. “No matter what your health needs or political needs are, the process cannot be readily hurried.

“Scaling up to Phase 3 trials and taking time to monitor and process the results cannot be hurried if we want to assure both safety and efficacy.”

“Massive funding has allowed us to pursue dozens of lines of inquiry simultaneously, rather than choosing a few and waiting to see how they pan out across clinical trials before proceeding. But scaling up to Phase 3 trials and taking time to monitor and process the results cannot be hurried if we want to assure both safety and efficacy.

“The advantages of genetic approaches to vaccine development are they are less risky for recipients than using whole viruses and once identified they can be produced for distribution more rapidly than traditional vaccines. However, the whole viral approach (the original method) has the great advantage of being tried and true, and many vaccines in use depend on inactivated viruses.”

What about herd immunity?

Some Americans, including some government officials, have been focused not on vaccine development but instead on something called “herd immunity.” And there are ethical concerns with this concept too.

By Tkarcher, wikimedia

Herd immunity happens when a sufficient percentage of a population has become immune to a particular viral infection, whether through vaccination or previous infections. At some point, it becomes too difficult for the virus to keep transmitting through immune carriers.

That threshold for COVID-19 is thought to be somewhere between 60% and 80% of the population.

“Herd immunity doesn’t kill anybody,” Wheeler said, but getting to herd immunity inevitably will.

“The path to herd immunity requires the infection of 80% of the population, and mortality rates with this disease vary dramatically according to age, underlying health, health care access and economics,” she explained. “Yes, herd immunity will work eventually. How long will it take and how many lives will it cost?”

Notably, those most likely to be sacrificed in a quest for herd immunity would be senior adult, poor people, persons of color and those with underlying health conditions.

To understand the math behind this, begin with the total population of the United States, about 330 million. Conservatively, calculate that 80% of that population would have to be exposed to the virus to reach herd immunity. That’s 264 million people. Then figure the mortality rate of COVID-91 in the United States, which is about 2.5% of those infected. Multiply 264 million by 2.5% — and the possible number of deaths required to reach herd immunity in the United States alone could be as high as 6.6 million.

Even assuming on the low end a 50% infection rate to reach herd immunity — meaning 165 million people infected — results in 4 million deaths. Other more nuanced models produce an estimated death toll of 1.4 million Americans.

Herd immunity would require somewhere between 1.4 million and 6.6 million U.S. deaths without a vaccine.

So herd immunity would require somewhere between 1.4 million and 6.6 million U.S. deaths without a vaccine.

“Are we ready for that? Is that the best we can do?” Wheeler asked.

And even if herd immunity were to work, it might not last, she added. “The reason viruses are so potent is that they are not alive and they mutate freely because they don’t have the constraints of a full-blown organism. Even if we were willing to wait the years and suffer the number of deaths we are talking about, it’s not clear we would be safe. The virus would be likely to change its form to reinfect. This is why we get a flu vaccine every year, because the virus mutates.”

Related articles

Jesus and socialism? A conversation with Sondra Wheeler | Analysis by Jason Koon