Remember those quaint days when some people tried to ban the Harry Potter books from libraries because they were sure kids would learn how to cast spells if they read the fictional accounts of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry?

Yeah, those days are still here. As recently as 2019, the Harry Potter series still made the American Library Association’s Top 10 list of most-challenged books nationwide.

But in the two years since, the stakes have gotten higher and the number of book challenges happening in public libraries and school libraries has skyrocketed faster than Harry Potter playing Quidditch on a souped-up broomstick.

And it’s a good thing Harry Potter isn’t Black or gay or transgender, because his fate would have been worse for sure. Challenges to books about fictional magic and wizardry have been supplanted by concerns about sexuality, sexual orientation, gender identity, race and politics.

“It’s a good thing Harry Potter isn’t Black or gay or transgender, because his fate would have been worse for sure.”

“We’re seeing an unprecedented volume of challenges in the fall of 2021,” Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the ALA’s office for intellectual freedom, said in late November. “In my 20 years with ALA, I can’t recall a time when we had multiple challenges coming in on a daily basis.”

‘A dramatic uptick’

This trend is so alarming to the ALA that its executive board on Nov. 29, 2021, issued a statement warning of “a dramatic uptick in book challenges and outright removal of books from libraries.”

A book challenge is what happens when a patron or parent lodges a complaint about a book in a library, which typically prompts a review. A book ban is when a title is removed from a library’s shelves or placed under restriction.

In 1999, with the first American publishing of a Harry Potter title, book challenges took a new turn in the U.S. Previous concerns about discussions of sexuality or obscene language in books gave way to new concerns about witchcraft. That trend continued for a decade, but riding along with it remained a simmering thread of angst about perceived obscenity and age-inappropriate discussions of sexual issues — mostly fueled by conservative Christian parents.

In 1999, with the first American publishing of a Harry Potter title, book challenges took a new turn in the U.S. Previous concerns about discussions of sexuality or obscene language in books gave way to new concerns about witchcraft. That trend continued for a decade, but riding along with it remained a simmering thread of angst about perceived obscenity and age-inappropriate discussions of sexual issues — mostly fueled by conservative Christian parents.

Then with the radicalized white supremacy unleashed by followers of Donald Trump in 2016, followed by the nation’s summer of racial reckoning in 2020, book challenges turned increasingly toward matters of race and sexuality. What was happening on the national political scene began to make its way to the local level through confrontations at school board meetings and city council meetings. Often, books were the vehicle to present the underlying complaints.

“In recent months, a few organizations have advanced the proposition that the voices of the marginalized have no place on library shelves. To this end, they have launched campaigns demanding the censorship of books and resources that mirror the lives of those who are gay, queer or transgender or that tell the stories of persons who are Black, indigenous or persons of color,” the ALA’s November 2021 statement begins. “Falsely claiming that these works are subversive, immoral, or worse, these groups induce elected and non-elected officials to abandon Constitutional principles, ignore the rule of law, and disregard individual rights to promote government censorship of library collections. Some of these groups even resort to intimidation and threats to achieve their ends, targeting the safety and livelihoods of library workers, educators and board members who have dedicated themselves to public service, informing our communities, and educating our youth.”

(123rf.com)

Separately, the ALA announced that in the three-month period between Sept. 1, 2021, and Nov. 30, 2021, its office for intellectual freedom had handled 330 unique book challenges. That brought the number of challenges for 2021 to a level double that recorded in 2020 — the first year of the pandemic — and outpaced 2019. Final data for 2021 will be released by the ALA on April 4, during National Library Week.

The EveryLibrary Institute and EveryLibrary are working with Tasslyn Magnusson, an independent researcher, to document every book banning and book challenge in school libraries and public libraries. An online spreadsheet shows detailed information about book challenges and bans by location, title and outcome.

Who sets the standard?

Book challenges are integrally related to the unrest at school board meetings across the nation over the past year. While one theme of angry parents has been about opposition to masks and vaccines to prevent the spread of COVID, a parallel theme has been about sexuality, gender and race.

And these three things almost always go together in parent protests.

In brief, mainly white evangelical Christian parents who believe sexual orientation is a choice, who do not believe gender dysphoria is real and who want to believe they are “colorblind” to race — these same parents also want to ensure that public libraries and public schools enforce their personal standards on the community.

“Mainly white evangelical Christian parents who believe sexual orientation is a choice, who do not believe gender dysphoria is real and who want to believe they are “colorblind” to race — these same parents also want to ensure that public libraries and public schools enforce their personal standards on the community.”

These are, indeed, “sincerely held religious beliefs,” even if they are not majority views in the culture or community. The fact that conservative evangelical Christians fear the nation has abandoned Judeo-Christian values as they believe them lights the fire of their protests. And they sincerely believe that school officials and librarians should cater to their demands despite what any other parent, child or community member wants.

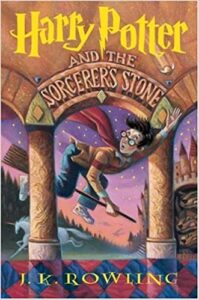

In public schools, the two most frequently named culprits of this rage are curriculum and books. Thus, conservatives have gone after Common Core Curriculum standards that were rolled out nationwide beginning in 2010. The Common Core is a set of academic standards in mathematics and English language arts/literacy with learning goals that outline what a student should know and be able to do at the end of each grade.

From coast to coast, 41 states and the District of Columbia have voluntarily adopted the Common Core. Four states never adopted the standards: Virginia, Texas, Alaska and Nebraska. Four states later withdrew from the standards: Arizona, Oklahoma, Indiana and South Carolina. And 12 states currently are in the process of repealing Common Core: Alabama, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, West Virginia and Maryland.

These 20 states are largely Republican controlled, as the Common Core has become a divisive political issue.

Status of Common Core in U.S. states.

Book challenges track with Common Core criticisms not only because of a similar ideological path but also because some of the disputed titles are recommended reading in the Common Core.

Thus, conservative parents blame the Common Core for “forcing” their children to read books they don’t think their children should read.

But more than that, the Common Core battle was a warm-up for the Critical Race Theory battle.

Writing in Education Week last year, Andrew Ujifusa explained: “Tension about the Common Core stemmed largely from disputes about the federal role in schools, and how teachers teach math. It represented perhaps the most prominent moment for an education policy community that for decades has focused on standards, accountability, and assessments. But it didn’t touch on profound divisions over American history and identity.

“Now, however, the divide in how people think about the role of race in America’s past and present, driven by events like the 2020 murder of George Floyd by a police officer, is reflected in the struggle over how schools should address racism as well as issues like sexism. The issue is more personal and profound than any government white paper or policy decision, and schools are grappling with it once again in a heated and fragmented political culture. Partisans, in turn, have used it to push schools farther into the national political spotlight.”

A case study: Toni Morrison’s first novel

For an example of one of the most-frequently challenged books in high school curriculum, turn to Pulitzer Prize- and Nobel Peace Award-winning author Toni Morrison’s first novel, The Bluest Eye.

The book was published in 1970. It tells the fictional story of 10-year-old Frieda MacTeer and 9-year-old Claudia at the end of the Great Depression. It is a story about family, financial pressures, race and trying to fit in. It also includes a graphic description of pedophilia and rape within the context of the larger non-sexual story.

The book was published in 1970. It tells the fictional story of 10-year-old Frieda MacTeer and 9-year-old Claudia at the end of the Great Depression. It is a story about family, financial pressures, race and trying to fit in. It also includes a graphic description of pedophilia and rape within the context of the larger non-sexual story.

Into the two young girls’ lives comes a girl named Percola, who loves Shirley Temple and believes whiteness is beautiful and that she is ugly. The book takes its title from Percola’s belief that if she had blue eyes, she would be loved and her life would be better.

However, the book contains a passage describing — in graphic detail — how Percola’s father has abused her and raped her. Morrison has explained that she intended the story to challenge readers to remember that not everything is beautiful and that childhood trauma is real. She wanted to describe how Black female children often feel vulnerable.

To read this controversial passage from the book, go here.

One reason The Bluest Eye is a good example to understand the challenge to library books in general is because the challenges and answers by now are well documented. After a 2017 challenge in Bumcombe County, N.C., one group created an entire website devoted to the case study.

Toni Morrison

A graphic passage from The Bluest Eye is referenced in a Letter to the Editor published by BNG on Feb. 15. That letter, from Oklahoma state Sen. Rob Standridge, explains why he introduced a bill in the state legislature that would allow any parent to demand the removal of any book “with perceived anti-religious content from school.” Further, the bill would have fined teachers a minimum of $10,000 — to be paid from personal resources — if they “offer an opposing view to the religious beliefs held by students.”

While the bill — which has now been withdrawn — was focused on a range of issues and not just books, Standridge’s response to a BNG opinion piece critical of his bill focused almost exclusively on the danger posed by books and specifically by Morrison’s 1970 book.

“Censoring material for a parent’s child is not banning books; it is both the right and obligation of parents, not the least of which Christian parents, to guard their child from materials that they deem inappropriate,” the senator wrote.

His letter also mentions Critical Race Theory, “transgenderism,” and “ideologies and anti-Christian themes” as reasons why the bill is needed.

A profile of challenged books

Of note here is that The Bluest Eye is a book written by a Black woman primarily about the life experiences of Black girls.

The ALA’s Top 10 list of most-challenged books for 2020 — for the first time in its history — included six titles that involve issues of race.

The ALA’s word cloud shows the most common reasons given for wanting to ban a book in 2020.

Often these titles are challenged under the guise of schools teaching Critical Race Theory, which has become the catch-all label for conservatives’ fears of their children learning the truth of America’s racist history and how it continues today.

NBC News sent records requests to nearly 100 Texas school districts in the Houston, Dallas, San Antonio and Austin regions and found that during the first four months of the current school year, 75 formal requests by parents or community members to ban books from libraries had been filed. “In comparison, only one library book challenge was filed at those districts during the same time period a year earlier, records show. A handful of the districts reported more challenges this year than in the past two decades combined.”

Regarding titles, the NBC News analysis found: “All but a few of the challenges this school year targeted books dealing with racism or sexuality, the majority of them featuring LGBTQ characters and explicit descriptions of sex. Many of the books under fire are newer titles, purchased by school librarians in recent years as part of a nationwide movement to diversify the content available to public school children.”

Matt Krause

Among many examples of book protests nationwide, few rise to the level of Texas state Rep. Matt Krause and his list of 850 books he says should be removed from all school libraries immediately. Krause wrote a letter to the Texas Education Commission and all school superintendents in the state demanding that they respond with reports of which and how many of these objectionable books are in their libraries.

This came on the heels of Texas Gov. Greg Abbott declaring there is “pornography” lurking in school libraries.

In addition to the 850 books on Krause’s list, he requested to know of any other library holdings that contain “sexually explicit images, graphic presentations of sexual behavior that is in violation of the law, or contain material that might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex or convey that a student, by virtue of their race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.”

Danika Ellis of the website Book Riot has published an extensive analysis of Krause’s 850 books to ban from school libraries. She reports the list is a mess, includes duplicates and books that are so old no school library is likely to shelve them and no modern teenager would read them.

But the most prominent theme she discovered in this list is an attack on anything having to do with sex or gender — and especially anything about LGBTQ persons.

Two other things stand out from Ellis’ analysis of the Krause list.

“Perhaps the most disturbing trend I saw in this list is the challenging of books that teach students their rights,” she wrote. “Of all the things to teach in school or for kids to have access to, this is one of the most important. To be clear, I’m not even counting books about reproductive rights or your rights as an LGBTQ person in particular. These are titles like The Legal Atlas of the United States, Teen Legal Rights, Gender Equality and Identity Rights (Foundations of Democracy), Equal Rights, We the Students: Supreme Court Cases for and About Students, and Peaceful Rights for Equal Rights.

“What does it say about an elected official that he would want books about students’ legal rights taken out of school libraries? Who considers it dangerous for kids to know their rights? Withholding information from students about their rights is incredibly unethical. Whether a parent or lawmaker agrees with every right students have, they should not be able to deny students’ access to knowing about them.”

And this bit of irony: One of the targeted books is The Year They Burned the Books by Nancy Garden. Ellis explains: “Originally published in 1999, it’s about a town’s controversy over the high school’s sex ed program, and a school board member tries to get all the sex ed material, including textbooks, removed from the school.”

And this bit of irony: One of the targeted books is The Year They Burned the Books by Nancy Garden. Ellis explains: “Originally published in 1999, it’s about a town’s controversy over the high school’s sex ed program, and a school board member tries to get all the sex ed material, including textbooks, removed from the school.”

National drivers of this movement

As with the school board protests sweeping this nation this school year — often about masks, vaccines, Critical Race Theory, race, gender and sexuality — a handful of national organizations are feeding the fury. Although some of these groups claim to be “grassroots” movements, the only movement appears to be from the national bodies down to parents who are recruited and encouraged to protest.

On the book challenge front, one of the foremost influencers is No Left Turn in Education, which describes itself as “a national grassroots movement of common-sense parents and community members from diverse backgrounds, building generational integrity through education free from indoctrination.”

Its website warns: “Radical teachings motivated by a political agenda and deliberately spread by teachers, administrators, school board members, and even state officials have infiltrated schools across the nation. Unfortunately, all too often words such as diversity, equity, inclusion, social justice, systemic racism, human rights education and health education concealed an aggressive, radical totalitarian ideology. From The 1619 Project to Critical Race Theory to Comprehensive Sexuality Education, the goal is to overturn our society by sowing divisiveness and hate. The social unrest that erupted in May 2020 provided the perfect cover for a complete assault and takeover of our educational system. Aided by the mainstream media, the teachers’ unions, together with an increasing number of educators and administrators have become the true schoolyard bullies, using taxpayer funds to indoctrinate their captive audience — our children.”

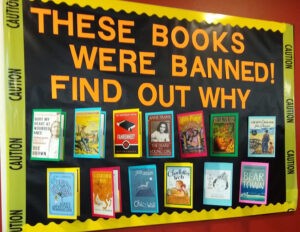

Bulletin board display at Danville, Ky., library.

In a recent letter to U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland, No Left Turn Executive Director Elana Fishbein called for a massive federal investigation into the “sexualizing” of children in schools. One of the examples of “depravity” she cited relates to library books.

“By depravity, I refer to the accessibility in schools of explicit and sexually charged books and related forms of information used in schools,” she wrote. “Minors are the intended audience for obscene and plainly pornographic content and visual graphics found in various book forms, in online curricula and library systems, in open resource material used by teachers without any check or balance, and many other forms of access which in some cases are designed to evade scrutiny, particularly scrutiny by parents and guardians.”

She concludes the letter: “This is a crisis! The normalization of child sexual exploitation continues in our publicly funded schools and libraries, addressed now only because its existence and reach have been so recently understood.”

No Left Turn publishes its own list of objectionable books — a much shorter list than Krause’s 850.

“These are the books that are used to spread radical and racist ideologies to students.”

“These are the books that are used to spread radical and racist ideologies to students,” the website says. “They demean our nation and its heroes, revise our history, and divide us as a people for the purpose of indoctrinating kids to a dangerous ideology. There are loads of these books for every reading and grade level. If you come across additional ones, please let us know and we will add them here.”

The book titles and their covers are shown and are organized in three categories: Critical Race Theory, “anti-police” and Comprehensive Sexuality Education.

Another similar group is Parents United America, which has numerous state chapters with similar names. Its website warns: “We are witnessing a radical shift in our country to circumvent the fundamental rights of parents and replace it with state guardianship of our children.”

The Resource page on this group’s website includes prominent links to information about home schooling and charter schools.

How to make sense of it all

Those who watch these issues closely from a neutral position see the current excitement about book challenges as deeply tied to two things:

- A backlash to the racial reckoning of 2020 and beyond. See how frequently the name George Floyd appears in the conversation from those who want to challenge books or challenge school boards.

- A runup to the 2022 midterm elections. For example, in Texas, Gov. Greg Abbott is up for reelection this year and faces two challengers from the far right who are attempting to portray him as a liberal. Matt Krause, who is waving around the 850-book list in Texas, is currently running to become district attorney in Fort Worth. Conservative movements to take control of school boards are running full throttle nationwide; having a handy talking point about “pornographic” books helps.

However, the challenge to huge numbers of books in public libraries and school libraries is real. Advocacy groups like Every Library and the action arm of the ALA are responding to these threats with lots of resources.

There’s even a group of suburban moms called Red, Wine and Blue that has created an online project Called Book Ban Busters. Its website explains: “Extremist politicians and outside groups are attacking our kids’ education. In fact, they’ve become SO extreme that they’ve resorted to book banning. They’ve even tried to ban books about Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks. Well, suburban women aren’t having it. This is not the 1950s. Every kid should be equipped for the 21st century, and that means learning real history (not fairy tales) and respecting people across our differences. It means ensuring every kid feels safe to learn and thrive at school.”

There’s even a group of suburban moms called Red, Wine and Blue that has created an online project Called Book Ban Busters. Its website explains: “Extremist politicians and outside groups are attacking our kids’ education. In fact, they’ve become SO extreme that they’ve resorted to book banning. They’ve even tried to ban books about Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks. Well, suburban women aren’t having it. This is not the 1950s. Every kid should be equipped for the 21st century, and that means learning real history (not fairy tales) and respecting people across our differences. It means ensuring every kid feels safe to learn and thrive at school.”

Every professional librarian — whether working in a school or city or county library — is trained in a standard process for receiving complaints about books on their shelves. This process documents the concern and then typically is sent to a review committee, where a decision is made to retain the book, restrict access to the book or, in rare cases, remove the book.

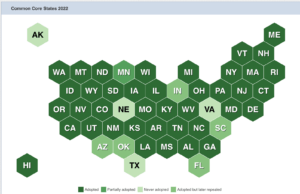

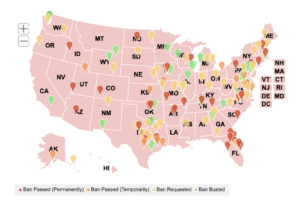

State of current efforts at book bans by state, as listed by Book Ban Busters.

Before the current moment, more than eight out of 10 challenged books stayed on the shelves after being challenged. Factors considered include the intended audience of the book and the overall content of the book. But today, the fear of conflict is causing some schools and libraries to remove books preemptively, without review.

Apart from legitimate and honest challenges, what’s happening across the country right now often falls in a different category that might be called a “weaponized” challenge. This is where someone who is not a stakeholder in the school or community may show up to attack a book or an author or where challenges arise from people who have not read the book or who are misrepresenting it for political purposes.

For example, someone legitimately challenging a book should be willing to follow the process provided by the library or school — not suddenly show up shouting at a school board meeting.

And someone legitimately challenging a book most likely will present an actual page from the book or a photocopy of the page — not an excerpt handed out by some other organization rallying opposition everywhere it can.

What is obscene and what is pornography?

The current politicized language around books in school libraries creates new barriers to communication. “Obscenity” and “pornography” are legally defined terms, not self-defined declarations.

“Even the Bible passes muster as an allowed library book, despite its descriptions of extramarital sex, polygamy, pedophilia, incest and rape.”

Generally, “obscene” material must refer to the preponderance of the work being obscene or pornographic. Thus, even the Bible passes muster as an allowed library book, despite its descriptions of extramarital sex, polygamy, pedophilia, incest and rape.

The U.S. Supreme Court in 1973 created what’s known as the Miller Test that asks three questions to determine what is obscene:

- Whether the average person applying contemporary community standards would find the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest.

- Whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law.

- Whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.

By this standard, Toni Morrison’s description of incest and rape in The Bluest Eye would not make the book obscene. That graphic content is a small portion of the totality of the book, and the overall purpose of the book is not to be titillating or appeal to a prurient interest.

Another rule of thumb: Something may be “graphic” without being “pornographic.”

Yet, there are more strict standards for materials created for or presented to children. And this is where the school library critics of today have taken their stand, claiming that even high school seniors often are legally “minors” and therefore should be protected from reading books their parents object to.

(123rf.com)

Academic standards such as the Common Core, as well as library holdings, are built on various levels of age-appropriate material. What’s presented in Young Adult Fiction is not the same content as preschool storybooks or second-grade readers.

Often, critics of controversial books fail to mention the age level of the audience reading the books they find objectionable. Again, The Bluest Eye is a high school junior assignment, not a middle school assignment. A school board or review committee may still determine it is inappropriate to assign, but in doing so they will take into account the intended audience.

The good of the whole

The American Library Association upholds a set of standards and best practices that aim to serve the whole community, not just the specific interests or demands of the few.

In its November public statement, the ALA condemned all “acts of censorship and intimidation” and said: “We are committed to defending the constitutional rights of all individuals of all ages to use the resources and services of libraries. We champion and defend the freedom to speak, the freedom to publish, and the freedom to read, as promised by the First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.

“We stand opposed to censorship and any effort to coerce belief, suppress opinion, or punish those whose expression does not conform to what is deemed orthodox in history, politics, or belief. The unfettered exchange of ideas is essential to the preservation of a free and democratic society.

(123rf.com)

“Libraries manifest the promises of the First Amendment by making available the widest possible range of viewpoints, opinions and ideas, so that every person has the opportunity to freely read and consider information and ideas, regardless of their content or the viewpoint of the author. This requires the professional expertise of librarians who work in partnership with their communities to curate collections that serve the information needs of all their users.”

And, the ALA notes in the Q&A section of its website, its own Library Bill of Rights already addresses parental rights. That statement declares: “Librarians and governing bodies should maintain that parents — and only parents — have the right and the responsibility to restrict the access of their children — and only their children — to library resources.”

Related articles:

It’s time to stop the insanity that is killing public education | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Letter to the Editor: A response from Oklahoma Senator Rob Standridge

Texas Baptist Congressman attacks public school advocacy group on Twitter

Who’s behind the nationwide attacks on local school boards over Critical Race Theory?