By Jeff Brumley

Worship wars have existed throughout Christian history — the experts will tell you that.

They’ll also tell you that the debate has increased in significance as the modern church struggles to attract and retain members in a postmodern and post-Christian culture.

But two authors also say they’re seeing signs that church leaders are embracing ancient forms of worship that transcend cultural fluctuations — and that may be key for the church’s survival at a time when those who shun faith outnumber those who embrace it.

‘That ancient stuff’

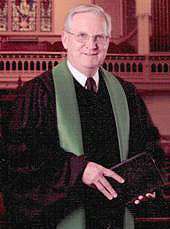

Though many of the recent worship battles have focused on style, style doesn’t really matter, said J. Daniel Day, retired senior professor of Christian preaching and worship at Campbell University Divinity School in Buies Creek, N.C., and author of the 2013 book Seeking the Face of God: Evangelical Worship Reconceived.

“Worship can be facilitated and used around any kind of style,” says Day, a former pastor of First Baptist Church in Raleigh, N.C. The music and sanctuary decorations can be tailored to fit the tastes of the congregation. “But the question becomes … ‘where’s the beef?’”

By that, Day says he means the object of worship, which should be God. But over the centuries, the purpose of worship in many evangelical churches has been to attract and evangelize new members.

That means turning the focus away from the Body of Christ and God, he warns.

That means turning the focus away from the Body of Christ and God, he warns.

That approach had its birth in American revivalism and lives today in worship that often ignores the historic Christian view of the church as a body of believers focused on God.

“The gathering of the people becomes about the outsider rather than the community of faith,” Day said. “It becomes effort to evangelize rather than to worship.”

Another major shift away from historic Christian worship came even earlier, he added.

“The whole emphasis coming out of the Reformation was to convert worship into an educational experience,” Day said. “So you had these didactic, Calvinist lectures that became the models for today’s teaching sermons that go on for 45 minutes to an hour.”

At that point, churches ceased being places of worship. “The sanctuary becomes a lecture hall.”

Or they become entertainment centers, Day says, where worship is about “being impressed by the magnificence of the place, the costumes and the jumbo screens.”

Rather than just being an annoying difference of opinion with those who think differently, Day says these trends are damaging and contribute to the exodus of Millennials and others from American churches.

It’s fine to hold a service for seekers, but worship itself should not cater to a demographic, he says.

A growing number of scholars from a variety of traditions are exploring the value ancient approaches to worship can have in modern times, he adds.

One is to provide a sense of authenticity and rootedness in the history and practice of the ancient church. It’s a value many of the so-called “nones” and “dones” say they find attractive — and often unavailable — in evangelical churches today.

“Can’t we go back,” Day asks, “and appropriate some of that ancient church stuff?”

‘Why did we lose that?’

That’s precisely what is happening in many Baptist and other Protestant traditions, says Derek Hatch, assistant professor of Christian studies at Howard Payne University in Brownwood, Texas, and co-editor of the 2013 book Gathering Together: Baptists at Work in Worship.

The growing embrace of historic worship forms is evidenced by the number of Baptist seminaries founded in the past 25 years. Most of those schools have encouraged deep explorations of Baptist and Christian history and practices.

The growing embrace of historic worship forms is evidenced by the number of Baptist seminaries founded in the past 25 years. Most of those schools have encouraged deep explorations of Baptist and Christian history and practices.

“It’s not just Baptists telling Baptists what Baptists have always said,” Hatch says. “There is a sense that we are participating in something bigger.”

And that includes the liturgical and sacramental ways in which Christians historically worshiped.

“Worship classes aren’t just about [teaching] three songs, a sermon and an invitation,” he says.

Hatch says such coursework opened his eyes to a wider range of approaches to connecting congregations with God. He knows of many others who have had the same experience.

One important way is by re-visioning worship as an act that shapes belief, instead of the other way around.

Such an approach can actually end up drawing visitors to the faith.

“There’s sort of an opening there — a fellowship — that can open doors down the line.”

Baptists in the 21st century aren’t the only ones to have experimented with liturgical worship. A decade ago, Hatch says, the emergent church movement introduced “postmodern worship” characterized by candles, darkness, colors, images and smells.

“That’s not entirely different from what the church did before,” Hatch says. “Why did we lose that?”

Regaining liturgical worship and intentionality around baptism and communion could help the church reverse declining attendance trends.

“It’s really not about style, it’s about thinking intentionally about a seamless garment — a unity of word and deed in which all these things tie together,” Hatch says.