The real estate value of a church’s land is usually irrelevant. There’s no property tax, and unless a church is ready to sell its land, the fluctuations in value over the years don’t matter much.

Until the property becomes too valuable to ignore.

That’s the case for Houston’s South Main Baptist Church, a church with nine ministers and about 475 worshipers in the pews on an average post-COVID Sunday. A church that, in 1930, moved to its current location in Midtown.

Now, the church finds itself at the center of the city’s so-called Innovation District, where Rice University’s endowment company is developing a corporate research and development campus and the city is planning to build a public transportation hub and to sink a nearby interstate for a walkable downtown.

Clint Pasche

“When we started seeing and hearing and learning more about what Rice was doing across the street, it became quite clear that there was just great opportunity,” said Clint Pasche, chair of a church committee tasked with exploring what it all means for South Main. “Not knowing what this is or where it’s headed, what we knew is that we didn’t have a plan.”

So South Main is investing $2.1 million in a master plan to make sure the church is deliberate about making the most of its assets. That’s the first step in what could be a multi-step process or in what could result in no action at all. At this point, the congregation has voted only to authorize the study; whatever will result is unknown.

Under one scenario, for example, if the congregation were to move forward with a property development plan, leaders expect ground leases could bring in as much as $2 million in annual revenue, a transformational amount for a church with an annual budget just north of $4 million.

That’s an unusual position for Baptists churches, which more often tend to sell valuable property than to develop it. Many churches in other denominations have successfully used legacy property to boost income that can be used for church operations and ministries.

For example, Episcopal churches have a history of property development. Trinity Wall Street was given land in lower Manhattan by Queen Anne in 1705, and the increase in value in the ensuing 300 years, along with wise property management, has boosted the historic church into the billionaire’s club. St. Michael and All Angel’s Episcopal Church in Dallas is planning a commercial development on a piece of property in its high-end neighborhood in University Park.

South Main Baptist Church

With the green light this month from the congregation to develop a master plan, South Main intends to spend next year developing a plan with outside advisers. The congregation would vote on the plan in 2024.

“I think it’s an extraordinary blessing, and to have a congregation that isn’t afraid of a blessing,” said South Main Pastor Steve Wells. “God has trusted us with this place and this time, and we want to be as faithful stewards as we can possibly be and bring in the smartest people to ask what we can do.”

The church will engage HR&A advisory group (whose client list includes Trinity Wall Street) and work with a master plan management company, Transwestern Development Co., which is handling the Rice development. The church is deliberating whether to borrow $2.1 million to cover advisory costs, or to draw from its endowment.

The change in the neighborhood that prompted church leaders to consider its own real estate development options is the innovation district developments next door. When Amazon went looking for a second headquarters in 2017, Houston applied, and leaders expected to get serious consideration. Instead, Houston didn’t make the top 20.

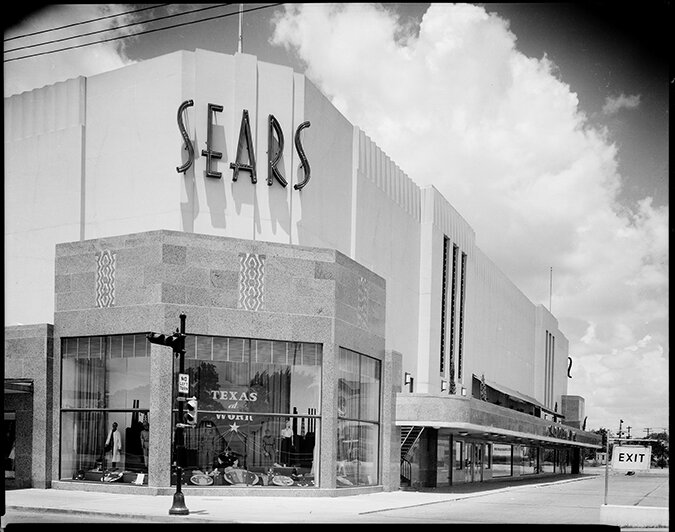

Historic Sears building

That prompted city leaders to develop the Innovation District around South Main Baptist, leading Rice Management Company to turn some land it owns in the neighborhood into the innovation campus. At the center of the campus is the refurbished Sears building, now called the Ion building, with some major corporate STEM tenants. Rice’s master plan is to expand the concept to adjacent property it owns. South Main Baptist Church is so close that the church’s façade can be spotted in the Rice project renderings.

With the intense real estate activity next door, South Main assembled an 11-member task force early this year to consider the church’s options. The church has several buildings and parking lots spread across an urban campus of nearly 15 acres. The group recommended the church hire advisers and spend 2023 coming up with a master plan for how best to use the property for its own needs, and to determine what parcels — if any — could be turned to revenue production. A ground lease — leasing land to a developer rather than selling — was determined to be the best combination of revenue and control over how the property might be used by a developer.

“We are not approaching this project from a position of weakness,” Pasche said. “We’re not trying to fill a budget hole or anticipating a smaller congregation. … It’s to have the financial freedom to finance some work that we know is going to pay dividends down the road.”

He added: “But if we get the plan and decide the market isn’t ready or we aren’t ready, we aren’t going to have to make a move because we’ll have to shut the doors in a few years.”

The Ion

The task force held listening sessions with the congregation to understand what people like about the historic buildings and what doesn’t work. While people love the sanctuary, the chapel and a garden and fountain area, there was consensus that some structures, originally designed strictly for functionality, are ugly.

Paster Wells said in the congregational vote to move forward to develop a master plan, only two people voted no. “I did not sense anxiety in the room,” he said.

South Main leaders say they are determined to remain focused on using money for ministries and “kingdom work.” Gentrification has called the church to serve several very different populations: the current congregation, lower-income legacy neighborhoods near the church, and high-income professionals working nearby. While South Main already holds weekly church services for homeless people and has adopted a neighborhood school, the church has ambitions to become a place of respite for 9-to-5 professionals who need a break from work and a church home for their families.

“That building is filled every single day with some of the brightest minds in Houston,” Pasche said of the Ion building. “So how do we as a church draw them into what we are doing?”

Elizabeth Souder-Philyaw is a freelance writer based in Dallas. She most recently worked as an editor with the Dallas Morning News.

Related articles:

7 dos and don’ts when considering the redevelopment of church property | Opinion by Rick Reinhard

Before you make church property decisions, consider your mission and calling

Maybe seminaries should offer a class in mergers and acquisitions | Analysis by Mark Wingfield